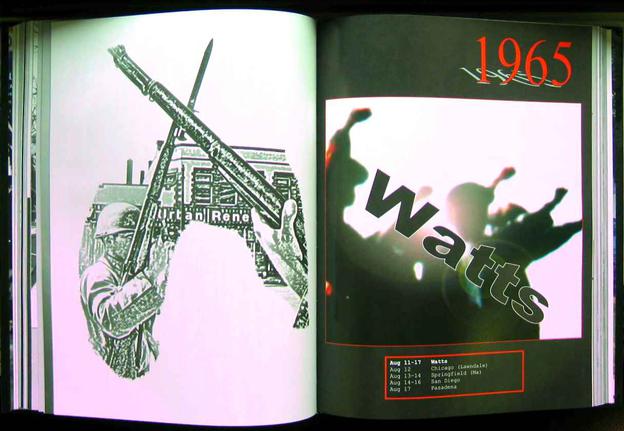

Watts Riot - 1965

After the summer of ‘64 begrudgingly faded into memory and the East coast riots were just a byline on page ten, America hoped there would be only a mild aftershock the following summer of ‘65. But 1965 would be no aftershock. The Watts riot of 1965 would be an eruption of such magnitude it would shake the country to its democratic foundation.

The upheaval that detonated in Watts stunned the nation. The horrific violence and upheaval that defined Watts shattered one illusion. Rioting was no longer an East coast phenomena, it was now a dilemma of national proportions. Watts would be the standard-bearer for the three hundred riots that would follow it. For every big city had a ghetto and every ghetto had for decades been experiencing the exact same grievances: hatred and mistrust of the police departments, unending poverty, discrimination, despair, hopelessness. Once the Watts uprising got started it dominated the evening news across the country. The cryptic nature of Watts forced even long time Los Angeles residents to break out a map to find out where it was. By the end of the week it would be indelibly etched in the minds of every American.

Watts galvanized ghettos across the country, not only to rise up against their oppressors but to unleash their considerable pent up fury against them. Tiny Watts, a paltry two square miles in area, would become a national logo for rebellion.

By sifting through an abridged history of Watts a certain fatal pattern of events emerges. Linking them together readily illuminates this once dark and confused picture that President Johnson initially saw. With this in mind, one can rationally begin a countdown to conflagration and begin to understand why south central Los Angeles became an icon for upheaval.

Watts - The Standard Bearer

Typical Watts neighborhood of the 1960's. Watts was a geographical antithesis of Harlem. Watts was a hybrid - part one and two story stucco houses sporting palm trees and wide streets, and part public housing with a smattering of Fred Sanford type junkyards to complete the landscape. While not Beverly Hills, it certainly wasn’t the drab, cloistered ghetto that Harlem had become. But make no mistake, Watts could be a very rough place.

Children frolic in the shadows of the Watts towers. Built between 1921-54 by immigrant Sam Rodia, he named them “Nuestro Pueblo” meaning “Our Town.” For Rodia, the Towers were a gift to his adopted country, an artistic symbol of peace. The closeness that "Our Town" implied back in Sam Rodia’s day would quickly dissolve amidst the ever changing postwar world. The economic boom that hit Los Angeles after WWII would drastically alter the ethnic make up of Watts.

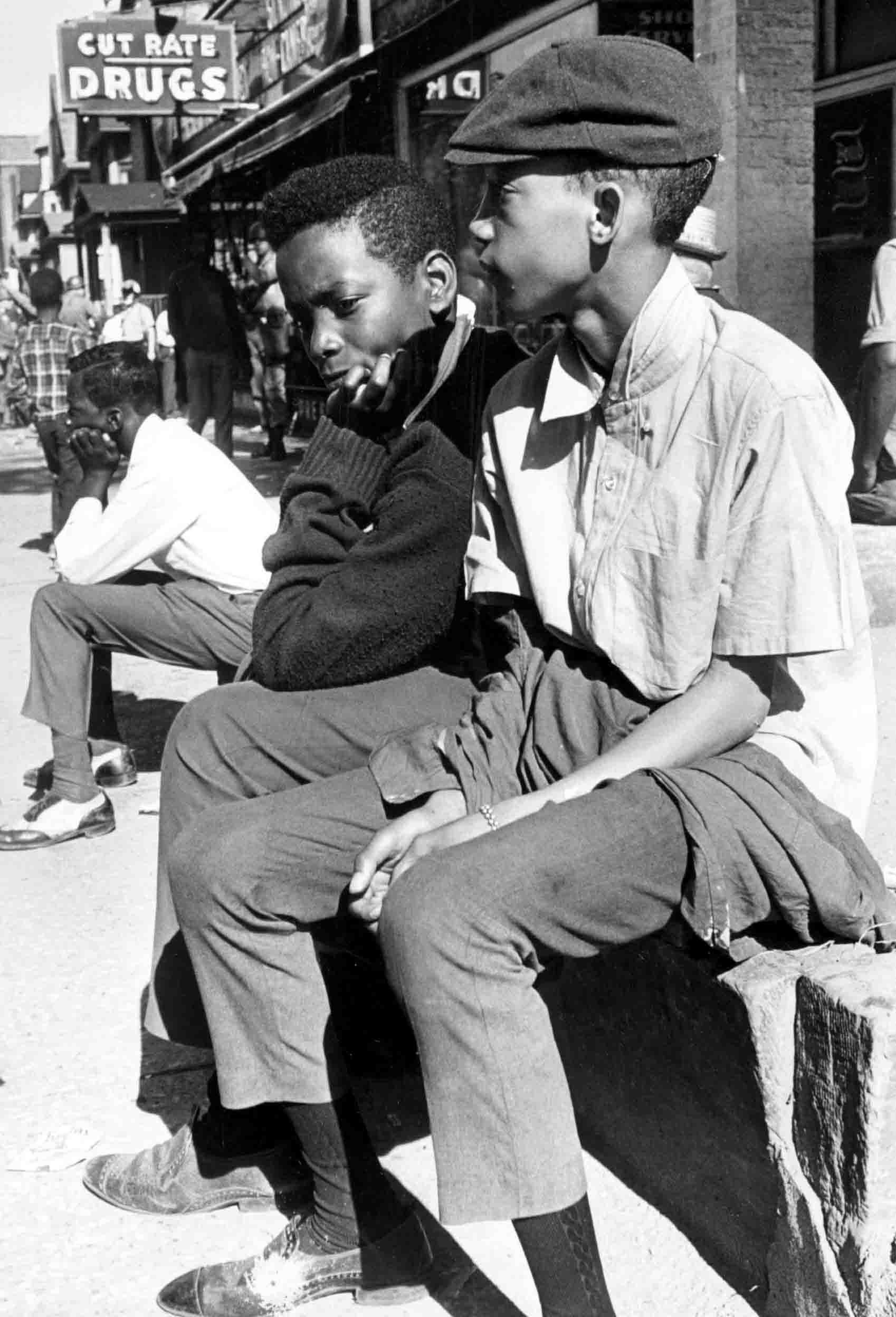

One of the most important ingredients for spawning riots is frustrated youths, and Watts had plenty of them.

By 1960, 60 percent of Watts was under the age of twenty-five. These are the ages when young men’s dreams are supposed to be coming to fruition. Instead, they were constantly reminded of their failure. In Watts, bankrupt of opportunity and stifled with oppression, life became a daily struggle just to keep the grim reaper at arms length.

In a gang and street corner society, it is of paramount importance for teenage boys to have adequate recreational facilities. When this is not the case, idle minds and considerable energies are certain to find a negative outlet.

Opportunity, also, must be made readily available for all. Kids bear witness to the traditional escalator of American progress they see on TV but know their futile predicament excludes them from those basic Americanisms that most of us take for granted. The resentment turns into bitterness as young boys come of age and approach adulthood spiritually broken.

A product of a poor educational system, and often, a broken home, he comes to the painful realization he does not have the skills to compete and looks to crime as an alternative. Technological automation and an ever shifting industrial base greatly eroded the employment picture in Watts over the decades, yet southern immigrants continued to enter Watts. With jobs locally in short supply, kids have to look elsewhere. Some may have to travel over an hour and spend $1.50 doing so for a job that pays only $6 or $7 a day. Without opportunity, the youth of Watts were doomed.

Riots in 1965

As news of the Watts rebellion trickled into Washington, government officials from President Johnson on down were aghast. How could this happen? The ink was hardly dry on the Voting Rights Act Johnson had signed just days previous to help empower the black community. “How is it possible,” a visibly shaken Johnson pondered, “after all we’ve accomplished? How could it be? Has the world gone topsy-turvy?” At first, Johnson believed the information must be skewed and demanded conformation. The pall of smoke hovering over Los Angeles confirmed his suspicions.

1962 – The cornerstone for rebellion is laid

Malcolm X in Los Angeles the year before the riot.

"You’ve got some Gestapo tactics being practiced by the police department in this country against 20 million black people, second class citizens, day in and day out – not only down South but up North. Los Angeles isn’t down South. Los Angeles isn’t in Mississippi. Los Angeles is in the state of California, which produced Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court – and Richard Nixon, the man who was Vice President of this country for some eight years and who wants to run for president again."

- Malcolm X - 1962

LAPD Chief William Parker

William H. Parker joined the LAPD in 1927, going to school at night to obtain his law degree. There was never any doubting his intellect or capacity, he was a professional student who thrived on academic challenge. He became chief of the LAPD in 1950 and lasted sixteen years in that tedious post when most of his predecessors rarely lasted two. Considered a very rigid and inflexible personality, he molded his department with dogged determination until it was considered by many as the elite police force of the 1960's.

As testament to this, the hit TV show Dragnet was modeled after Parker’s LAPD. No doubt there were numerous similarities between the unyielding Parker and the combative Joe Friday. Parker firmly believed the police had few friends and as such, knew they had to be a close-knit operation. Parker was highly vilified in the black community, who saw him as the personification of the white power structure. A skilled orator, he never turned down a request to speak to the public, which he constantly imbued with the theme of the police being the underdog. He had seen much in his thirty-nine years on the force but nothing, not even the Zoot Suit Riots of ‘43 could prepare him for the Watts uprising.

“Burn, Baby, Burn”

As is usually the case with riots, one of the triggering mechanisms is the aggravating summer heat and August 11th of 1965 found Los Angeles in the middle of a heat wave. The 92 degrees that the mercury registered made the air so hot you could smell the cement burning. In tandem with the oppressive racial atmosphere hovering over Watts, it took only a routine traffic stop to ignite the tinderbox that had accumulated for decades.

As California Highway Patrolman (CHiP) Lee Minikus was steering his big Harley north on Avalon, a black motorist pulled up beside him and warned of a drunk driver up ahead. Minikus spotted the suspect and pulled over twenty-one year old Marquette Frye and his brother Ronald just outside the Los Angeles city limits. Frye could not produce a driver’s license and Minikus had to establish that the vehicle was not stolen. Satisfied on that issue, Minikus now addressed the odor of alcohol on Frye’s breath. This required a sobriety test on the sidewalk which took more time. The multitude of street walkers which inhibit any big city on a summer day now began to stop and watch. As the minutes ticked by the crowd began to accumulate.

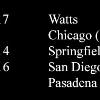

Marquette Frye (L) and brother Ronald

Initially Frye and Minikus had been getting along fine. It was a lively encounter as Frye was being quite animated in his explanations. So much so that not only was the crowd amused but so was Minikus. Frye’s house being only a block away, one of the spectators went to retrieve Frye’s mother, Rena. She was quickly hustled to the scene. According to Minikus, this is when the trouble started, “It was his mother who actually caused the problem. She got upset with the son because he was drunk.”

The embarrassment of his mother berating young Frye in front of so many onlookers was apparently too much for him. “He blew up,” said Minikus, “and then we had to take him into custody. After we handcuffed him, his mom jumped on my back, and his brother started hitting me.” The Frye's were forcibly arrested and hauled away but forty critical minutes had now gone by and a hostile crowd of two hundred had now accumulated. The seizure of the Frye's had greatly inflamed them and they would not be dispersed.

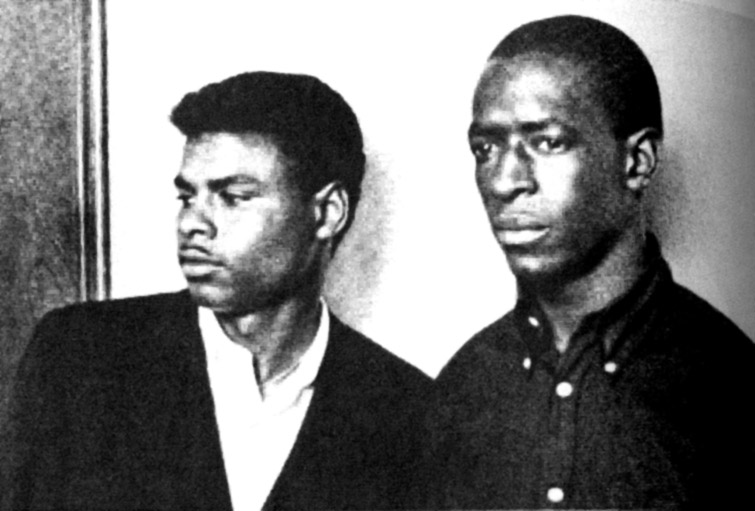

Cars were deluged with debris as they tried to run the gauntlet. Those who got through did so by the skin of

their teeth. Those who didn’t had their teeth knocked out and their vehicles turned over and set on fire.

The police left the scene and drove several blocks away to regroup,

hoping the situation would diffuse itself and the crowd would disperse

on their own with the police gone. They did not. In fact, the crowd

had swelled to almost one thousand people, mostly irate teenagers

and young men. The first indication of trouble came when a bus

pulled up to the huddle of policemen looking like it had driven

through a meteor shower. Its windows blown out and fraught with

dents, it testified to the gauntlet of rock throwers the police had left

behind.

For the mutinous mob back on Avalon, the freshly minted riot had

become a convenient medium for settling old grievances. As the

still unsuspecting white motorists naively entered the area, blood

curdling screams of “Get Whitey” were accompanied by a torrent

of bricks and rubble, anything to stop the vehicle and administer a

beating. Even light-skinned blacks, having been tainted with white

blood, were risking it.

Some presidents just come along at the wrong time in history. Although Lyndon Johnson's (seated at desk) presidency was tumultuous at best, some things he must be given credit for. He passed more civil rights legislation than any president since Lincoln, yet all of the riots happened on his watch. As the news of the Watts rebellion poured into the Oval office, the stunned president couldn't help but feel as if the black community had betrayed him.

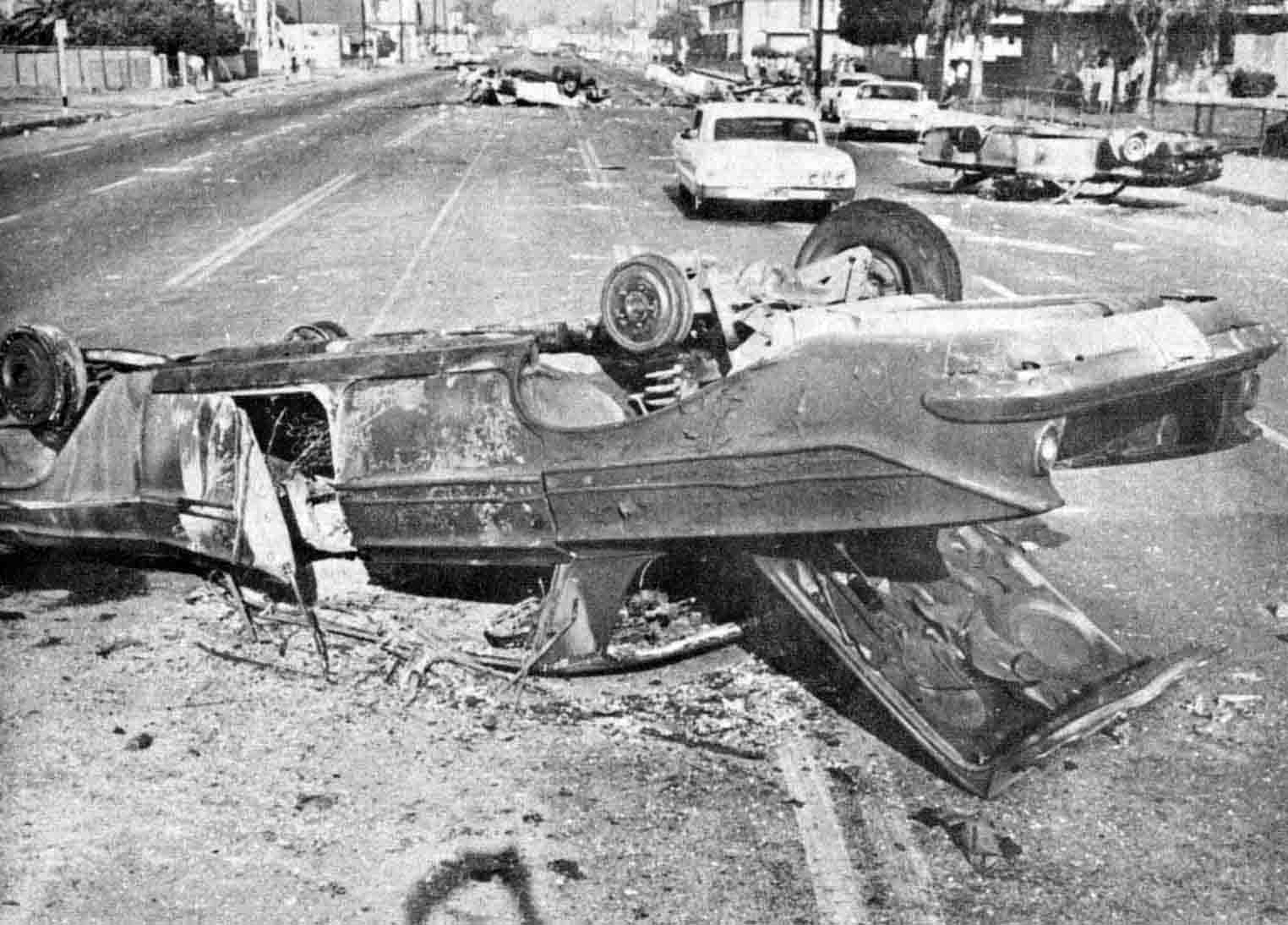

Local blacks who drove through the war zone gave the pass sign, one finger meant you were from Watts, two meant Compton and three meant neighboring Willowbrook. Anyone not hip to this code risked a serious beating or even death.

Looter gets choosy

Police road block

The grim reality of being a policeman - An overwhelmed Chief Parker laments the loss of one of his officers who was killed in a shoot-out. Parker expected and received a disciplined edge from his men. Despite his aloofness, he was well aware of the endemic evils the average beat cop encountered and the fallout which ensued: alcoholism, family conflicts, danger, high divorce rate and the feeling, real or imagined, of too little community support.

As a result, he was fiercely protective of his men and criticism of them was generally met with a cold glaze from his steely blue eyes and an equally abrasive rebuke. His steadfastness did not win him any support with his legion of critics. During the riot it was Parker and Mayor Yorty whom rioters pointed the finger at.

Marquette Frye was originally from a mining town in Wyoming. The education was better and the Frye’s were accepted by the near all-white population. “People in Wyoming were much better,” claimed Marquette. “In Wyoming, a human being is a human being."

"There were only about eight Negroes in the school. When we came to California, we got into an all Negro school. It was all new to us. I kept getting suspended for fighting. It wasn’t a racial thing because the whole school was Negro. It was a neighborhood thing. At school, if you lived were we did, you were considered ‘Watts.’ The other side was Slauson. If you’re Watts, then you run into trouble with the Slauson kids.”

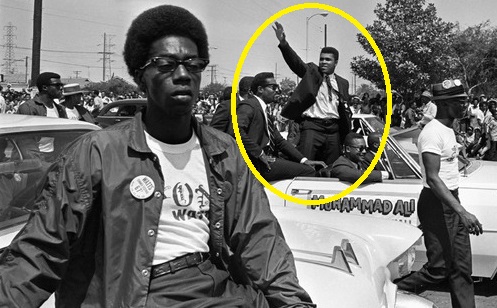

Martin Luther King’s nonviolent and multiracial methodologies were not endorsed by all blacks, as his visit to Watts during its last convulsions of anger demonstrated. His sequestered meeting with Mayor Yorty and Chief Parker was frigid and futile, Parker at times pounding his fist on the table to make his point and Yorty coldly suggesting that King “shouldn’t have come here.”

King arrived in Watts at the head of a ten car motorcade. The atmosphere in Watts was noxious with hate and King was greeted primarily with contempt by blacks who thought he was grandstanding. His attempts to reason with residents were constantly interrupted with both sarcastic barbs and highly personal invective's. A rioter recalls towards the end of the disturbance, “We went down to 103rd Street. Martin Luther King is coming down the street on a truck with (a) P.A. system: ‘My black brothers, why don’t you go home?’ People just ignored him, started throwing stuff at him.” King left Los Angeles virtually despondent, believing in some way he had failed.

As the King entourage walked the litter-strewn streets of Watts they had a memorable conversation with a hostile youth. “We won,” the youth exclaimed. King recoiled at the youth’s ebullience. “How have you won? Homes have been destroyed, Negroes are lying dead in the streets, the stores from which you buy food and clothes are destroyed, and people are bringing you relief.” The youth’s answer both startled and enlightened King. “We won because we made the whole world pay attention to us. The police chief never came here before; the mayor always stayed uptown. We made them come.”

Any lingering beliefs Dr. King may have had regarding any national solidarity were shattered. His excursion through Watts left him stunned. “We obviously are not reaching these people.” For King personally it was a terrible defeat, not one of his own making by any means but one that would require significant soul-searching for yet another distant and unknown answer.

King addresses a hostile crowd during the waning hours of the riot.

During the summer of 64', a year before the riot, Dr. King had visited the Nickerson Gardens housing project in Watts and came away believing there was an understanding between residents regarding the necessity of peace and what was required to achieve and maintain it. But as the fires of national discontent intensified, it was like pushing a rock uphill.

King, who sensed these riots coming as far back as the 1950's, knew that the tentacles of poverty spread violence and social stigma. His courageous attempts to relieve the mounting pressure in communities like Watts was to no avail. As ghetto despair morphed into volcanic anger, King himself began to have doubts about his effectiveness.

Los Angeles disc jockey would inadvertently coin a phrase that ignited a revolution.

Catchy phrases can gain traction in the strangest ways. When Los Angeles disc jockey Nathaniel "Magnificent" Montague worked in New York, he tried to indoctrinate the east coast with his hip slogan, "Burn, Baby, Burn" which innocently enough meant "Cool it" or "Dig it." It didn't catch on in Gotham.

When Montague tried it on his new audience in Los Angeles during the summer of 65', you could say it caught fire or rather helped induce it. As Watts began to burn the second week of August, young rioters feeling their pepper took Montague's slogan and flipped it into a rallying cry. Like a witch's incantation, rioters chanted "Burn, Baby, Burn" as cars and businesses were put to the torch.

Montague attempted to make amends in post-riot Watts by preaching his new slogan, "Learn, Baby, Learn," in an attempt to get

kids off the street and back to the classroom.

Famous nightclub comedian Dick Gregory grew up on the tattered streets of St. Louis during the Great Depression. Despair was his constant bodyguard. Endowed with a comedic flair often based on racist situations he had encountered throughout life, Gregory was a civil rights fanatic who specialized in defusing hostile situations between black and whites. Once again he would push his skills to the limit.

On Thursday, August 12, a second night of rioting ensued. After finishing his act for the evening, Gregory headed to the 77th district police station which presided over Watts. Presenting his credentials, the precinct commander gave him a bull horn and took him to the troubled area, Central Avenue and Imperial Hwy.

To the hundreds of jeering teenagers hiding in the shadows, Gregory bellowed into the bull horn, "Get your wives and kids off the street." For two hours Gregory pleaded for peace. Many now recognized the well-respected entertainer and obeyed, but some didn't. As Gregory tried to catch his breath between pleas, the rocks and bottles started to fly with an occasional gunshot until the comedian was hit in the leg.

Confronting the rifled man who shot him, Gregory commanded, "You shot me once, now get off the street."

Watts - Map

As is often the case when a fire devastates a forest, out of the ashen covered ground come new seeds which, now that virgin sunlight is upon them, a new life begins to bolt skyward. Such was the case with Watts during the summer of 1966 as residents searched for a healing process to salve the community wounds. The Watts Summer Festival echoed black heritage and culture as well as a star studded parade, musical acts and a beauty pageant. Just as a forest needs time to recover from a fire, so does a community need space to re-invent itself. It is a genesis.

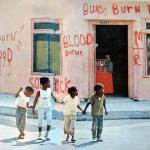

The Grand Marshall for the 1967 Watts Festival was Muhammad Ali. Ali, who only months before had been stripped of his heavyweight title for his refusal to enter the draft, was banned from boxing for three years.

Football great Roosevelt Grier - Grand Marshall of 1971 Watts Festival parade.

Dick Gregory

California National Guardsmen retake the badly scarred 103rd street which was the focal point of an army of rioters.