Detroit - Slice by Slice

1950: Detroit population reaches 1,850,000. Metropolitan population now 3,350,000.

1954: Northland mall opens in Southfield, a portent of things to come and the beginning of the

end for the giant Hudson's department store downtown.

1956: Ford builds new headquarters in Dearborn.

1956: A water plant in northeast Detroit opens as the burgeoning suburbs decide it is cheapest

1956: President Eisenhower's Federal Highway Act creates the interstate which further encourage

1956: General Motors follows Ford's lead and opens a state of the art technical center in suburban

1957: Eastland Mall, following the success of Northland, opens in suburban Harpers Woods.

1959: Legendary Detroit department store Kern's closes its doors for good.

1960: Detroit population declines to 1,670,000 people. Metropolitan population increases

drastically to 4,180,000. White flight now in full swing.

1962: Jerome P. Cavanagh, a little known lawyer, elected as mayor of Detroit with overwhelming black support. Detroit begins a remarkable turnaround under Cavanagh. Because of his

success, Detroit is viewed as the Model city due to Cavanagh's progressive policies and Detroit's unique capacity to provide middle class status to those of meager upbringings.

1965: In reaction to the increasing White Flight to the suburbs, the J.L. Hudson Co. develops

Westland Mall which opens in suburban Westland.

Westland Mall which opens in suburban Westland.

1967: Detroit riots occur opening the flood gates for White Flight to the suburbs. City will never

1970: Detroit population now tumbles to 1,510,000. Metropolitan population now 4,740,000.

1971: U.S. District Judge Stephen Roth orders cross-district busing, but it is overruled by the

1971: Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit closes 62 schools.

1972: Kmart Corporation moves its headquarters from downtown Detroit to Troy.

1972: Jeffries Freeway opens.

1974: Coleman Young becomes the city's first black mayor, a reign which will last 20 years.

1975: Detroit Lions abandon their home field of Tiger Stadium and move to newly completed

1980: Detroit population now at 1,200,000. Suburban population begins plunge also as

automotive industry begins a never ending decline, forcing many to leave the state.

The 1950s - A Most Damning Time

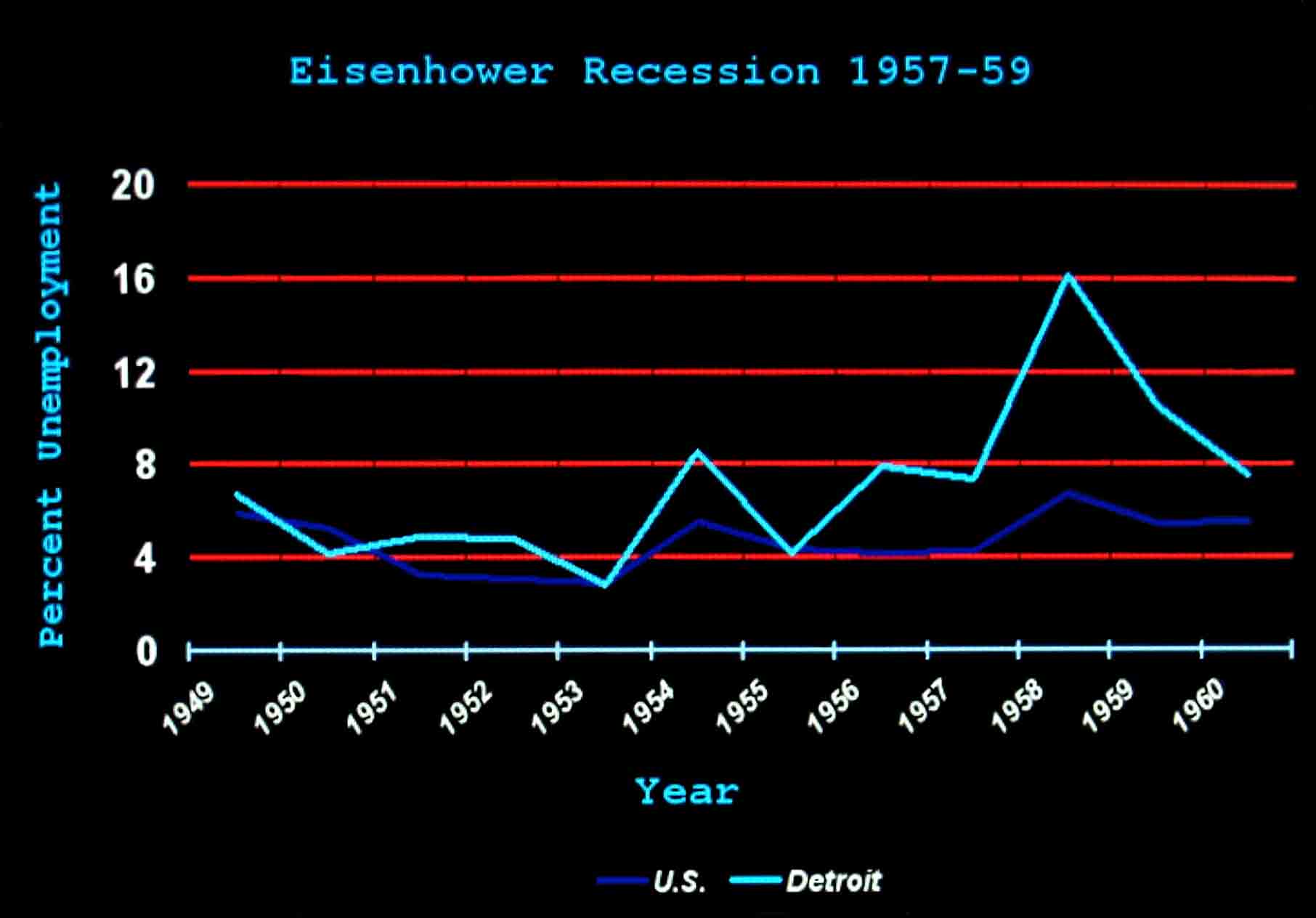

While many may feel that the 1960's were the pivotal decade in Detroit, the 1950's provided many secondary causes which helped grease the skids of anger and give it a final push towards rebellion. The three-headed monster of urban renewal, interstates and economic recession vastly altered the landscape of Detroit in the 1950's and would loom large as a socio-economic minefield that would cause the city to blow up in 1967.

Urban renewal, a term often associated with revitalization of decaying neighborhoods, was employed on a massive scale in Detroit during the 1950's and left a mark of still dubious distinction. Interstates carved up the city in the name of progress but its then unforeseen after effects would linger on like a ghostly apparition. Finally there was the Eisenhower recession of the late 1950's which shuttered many a Detroit factory, giving additional impetus to those seeking to bolt to the fledgling suburbs or leave the state altogether.

Still bathing in the victory of WWII which made the United States a superpower, American industrial might was unequaled in size or stature. World War II had forced Depression idled factories into a 24/7 frenzy of unprecedented production. Even the despot Joseph Stalin modeled his industry after Detroit.

But as the 1950's progressed, American industry once again began a painful throttling back to normalcy. Detroit, the city that put the world on wheels, had grown old before the eyes of its shocked citizenry. Time itself had weathered its buildings into tired and shabby shadows of their once youthful selves. The facade of strength and vigor was now a sad mirage. Detroit was looking more and more like a washed up welterweight.

Communities are by definition a group of people living together as a smaller social unit within a larger one having interests, work or kinship in common. Prior to mass transit, people often worked in the same neighborhood in which they lived. As the Eisenhower recession of the late 1950's raged across the country, Detroit’s factories began to shutter with alarming regularity.

This is the problem with basing your economy on just one industry, in this case automobiles. Communities are perpetually stuck in a feast or famine cycle. When times are good, like the 1910's or ‘20's, everyone gains and the neighborhood prospers. But when the industry hits a downturn everyone suffers.

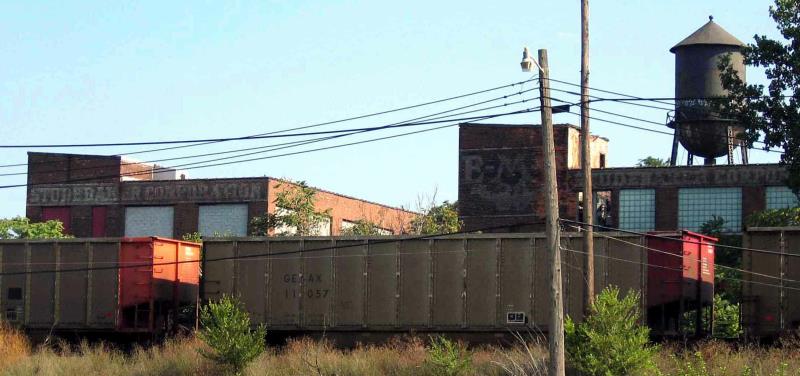

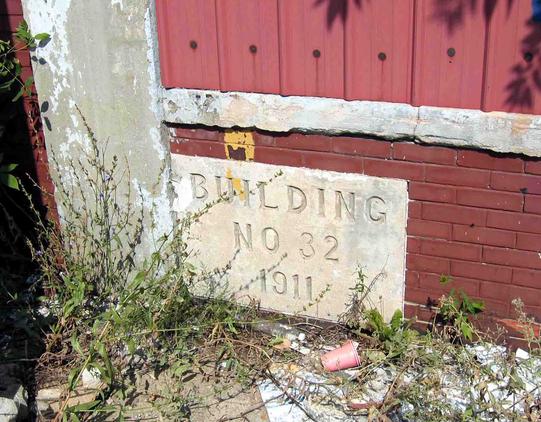

For decades Detroit was the greatest manufacturing city in the world. It was unmatched in its industrial capacity. Today, abandoned factories like the old Studebaker plant in Detroit’s Milwaukee Junction are now standing mockeries of their former glory. Now cold and silent, only periodic cornerstones mark the spots where legendary names once made their mark in life. The white building just past Studebaker is Henry Ford’s Piquette Avenue plant, birthplace of the Model T.

Still visible decades after abandonment, the faded "Studebaker Corporation" - "E-M-F Studebaker" sign still shows a glimmer of life long after its boilers went cold.

1960 - The end of Hudson Motors

When Detroit was King

Studebaker Automobile Company

Detroit's Piquette Ave. Studebaker plant in its heyday in the early 1900s.

Hudson

Motor

Company

Another giant in the auto industry, Hudson Motors was one of the last of the independents squeezed out by the Big Three during the Eisenhower recession in the late 1950s. Hudson Motors employed thousands of Detroiters during its peak. The never-ending consolidation of the auto industry would put Detroit on a one-way street to decline.

Detroit's Hudson Motor Car Company off Jefferson Ave, circa 1940s. Financed by department store magnate J. L. Hudson, the Hudson was a well-engineered and highly respected vehicle that dominated Nascar in the early 1950s. At its peak, Hudson was the third largest U.S. car manufacturer.

Looking more like an obscure Martian chess match, only the stubborn concrete stanchions of the demolished Hudson plant remained.

The final prize for the demolition gods, the powerhouse smokestack prepares to fall, sweeping yet another piece of Detroit’s storied past into the dust bin of history.

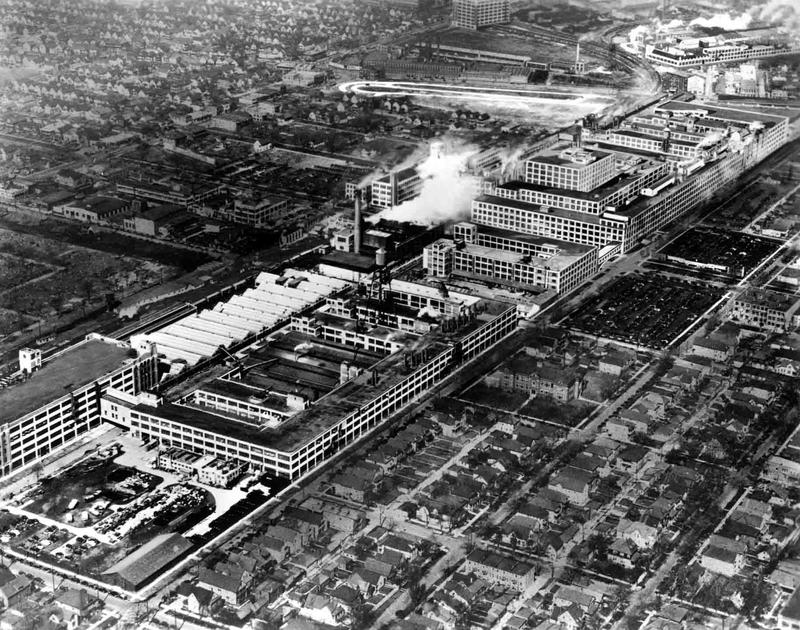

Packard Motor Car Company 1899-1958

The Long Arm of Packard - Begun in 1903, the complex would eventually

encompass some forty-seven buildings providing over 2.5 million square feet.

At its peak during WWII it employed 25,000 people. This aerial photo was

taken in 1937. Note that unlike its modern successors there were no parking

lots; as few people drove cars to work because they lived near by. Packard

was thus the cornerstone of the community and when it closed its doors for

good in 1956 the devastating economic domino effect spelled doom for the

neighborhood.

Packard in its prime

Packard today

(Right) A Packard cornerstone bespeaks of a time when the Motor City lion roared and the world watched in awe. A visitor to Detroit once described the city as the “sound of a hammer against a steel plate.” The cacophony of noise and energy was unrivaled by any city in the world.

During WWII, Detroit couldn’t come close to filling the jobs offered. But as the decades clicked past, the roar of the lion began to fade. By the 1960s the auto industry, which had always been erratic, was no longer a cash cow of employment. The once mighty lion was being transformed into an anemic mouse.

On Borrowed Time - The once majestic Packard building, which proudly basked in the glory and panache of the auto industry’s Gilded Age, now lies broken and abandoned, quietly awaiting the wrecking ball and an all too ignominious end.

Dodge Main

Nothing says 'old school Detroit' like the Dodge Brothers, Horace and John. Despite the tremendous accomplishments the two brothers packed into their all-too-short lives, perhaps what will always be remembered most about them is that they were brothers, in every sense of the word, as close as two brothers could be. Although not twins, John being the older by four years, they were as inseparable as twins generally are. This was symbolized in their company emblem of interlocking triangles.

Like a fire breathing dragon, Detroit's Dodge Main pulsates with life during its heyday.

John was the hard-nosed, tough-talking business part of the duo. He was also a notorious drinker who, with brother Horace in tow, left many a Detroit bar in shambles only to return the next day to

make amends with the owner. Horace was the engineering genius who could have a set of designs placed in front of him and at a mere glance suggest valuable improvements.

Dodge vehicles were some of the first to incorporate an all-steel body, making them extremely rugged and endowing them with the title of “Ram Tough”. Sales were brisk and success liberal as the Dodge brothers took the automotive world by storm.

But the tide of good fortune would ebb for the Dodge boys just as quickly as it had peaked. They found themselves at the New York Auto Show in January of 1920 just as the Spanish influenza epidemic was ragging across the East Coast. Both wound up contracting the disease. At first it appeared Horace would succumb while John looked on in utter horror. But just as Horace made a recovery John took a dramatic turn for the worse and died on January 14th. A grief-stricken Horace managed to hang on for another eleven months before succumbing to either the disease or, as many suspected, grief.

John Dodge

Horace Dodge

End of the line for Dodge Main and in many respects for Detroit itself. Hopelessly locked in a feast or famine economic cycle based on the auto industry from which it could not extricate itself, Detroit slowly withered like fruit on the vine while industry left for cheaper bases of operation. But make no mistake about it, Detroit raised the bar for industry the likes of which no other city has ever matched.

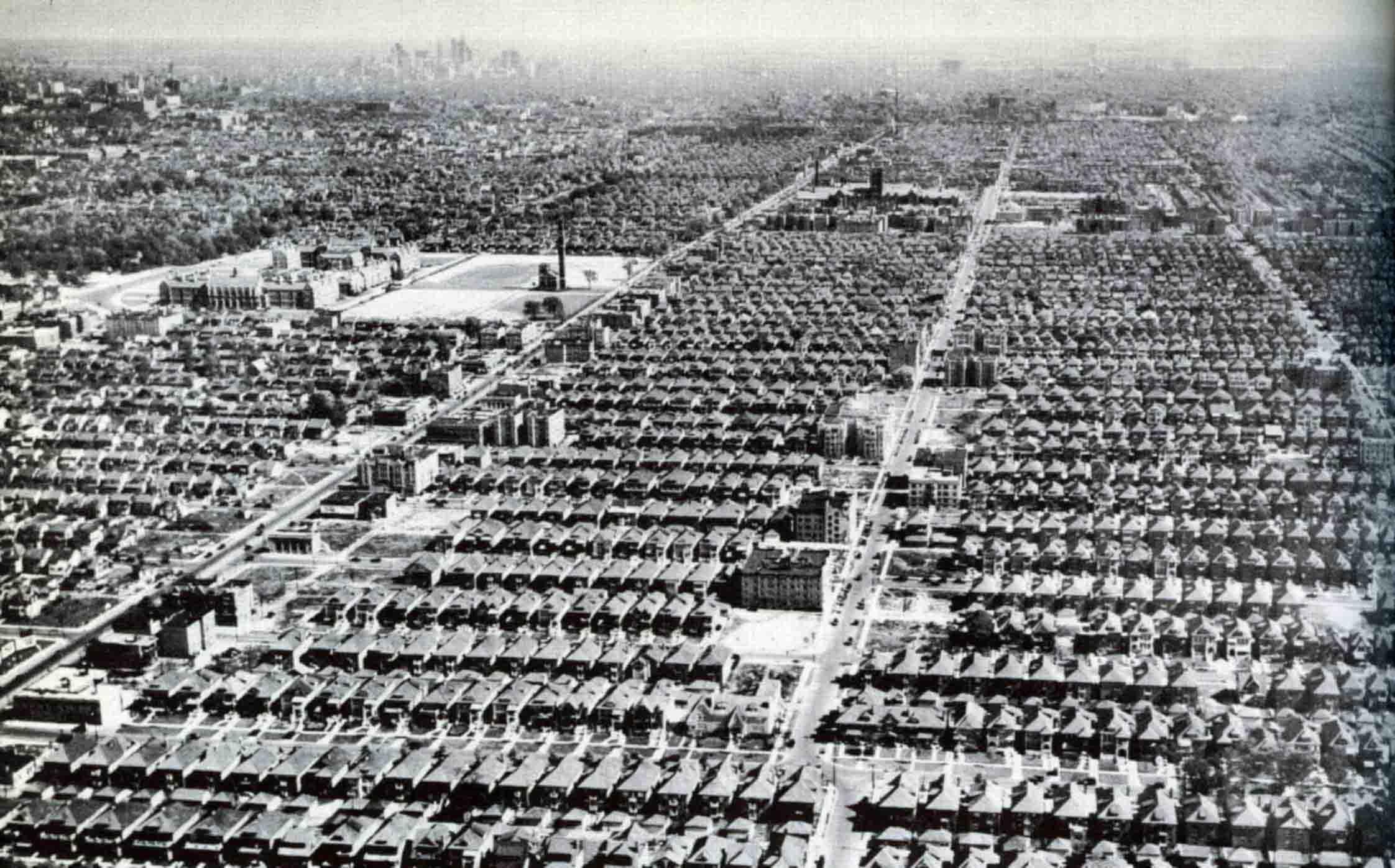

A 1950s aerial view of the Linwood area of Detroit. While the social condition of White Flight to the suburbs did indeed have racial connotations to it, of obvious note in this photo are the horribly cramped conditions in many neighborhoods. White Detroiters also dreamed of the "grass and garage" that the suburbs offered.

Studebaker - Abandoned

The Road to Detroit

1909-1954