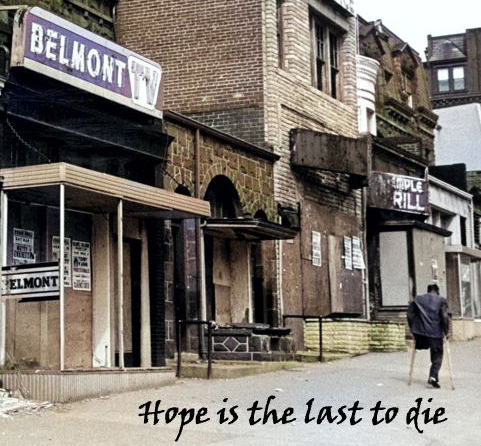

It wasn’t supposed to happen in Detroit - the city that had been the prototype Model City, the national yardstick for social progress. Detroit was the only city in the country that had two black U.S. Congressmen. Detroit had the largest chapter of the NAACP in the country at a staggering 18,000 members. Despite the mercurial nature of the automotive industry, Detroit industrial wages were the highest in the country. “Detroit has opened the golden door to the Negro,” said a black poverty worker after the riot. “But only a relatively few Negroes can get through that door at any one time. That’s the real trouble. In Jackson Mississippi, no Negro can get through the door, and strangely enough that can be kind of reassuring. He can always say it’s a white door and so there’s no use in a black man even trying. Some call it Negro laziness or apathy, but it’s the disease of the ghetto.”

"Look upon these ruins, citizens of Detroit and make your unbelieving eyes grow accustomed to them. For they will doubtless be with us for a long, long, time.”

The DPD: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

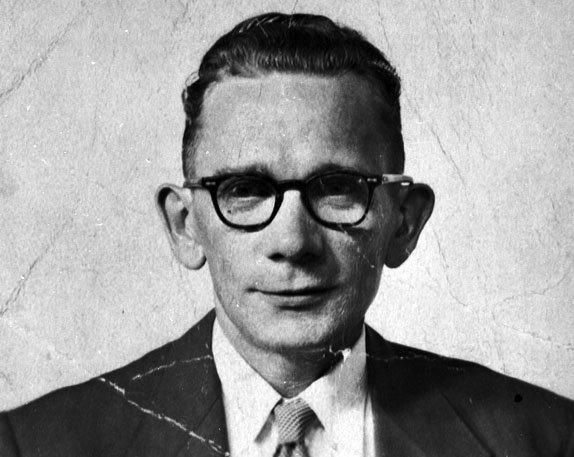

The Detroit Police Department withstood a firestorm of criticism after the riot but Police Commissioner Ray Girardin stood by his men, slowly whittling down the denunciations with his own assessment of the situation:

"Does the public expect a policeman to be a public executioner who can

inflict capital punishment for misdemeanors? It is one thing to shoot back at

snipers, and it is another thing to shoot down a child who is looting a pair of

shoes or even a television set. Property can be restored, but not life.

Society looks at policeman and blames them for the unrest. This is unfair.

Society has neither dealt with its problems nor equipped policeman to deal

with theirs, and it is time to get police work back into focus. In Detroit,

for instance, we have 4,500 officers to deal with a population of 1,640,000,

but also more than 700,000 civilians, some of them criminals, moving in

and out of the city every day. The role of urban police must be redefined,

and, obviously, better training and equipment will be needed.

The horror of a riot is easily visible, but the question of what force police

should exert applies to a wide variety of situations. On any summer night in

a major city like Detroit, the radio in my car may report, within five minutes,

that a woman has been knocked down, a suspicious person is roaming an

alley, a candy store has been robbed with one person shot, a baby is about

to be born in an automobile and a crowd is gathering in a ghetto.

In each case a man called policeman is supposed to solve the problem,

just as he was supposed to deal with the rioters."

Ray Girardin

Detroit Police Commissioner

The statue of Jesus, which adorns the front lawn of the Sacred Heart Seminary off Linwood, was painted black during the riot. It has remained that way ever since.

Boys will be boys - Post riot normalcy begins a slow return as two Guardsmen take in the Detroit scenery.

The Tailspin of Decline

Detroit, as the birthplace of the automobile, was seen as the symbol of the American dream. Immigrants came to Detroit, procured a good job, bought their first house and retired in peace. Post riot Detroit, in turn, became the poster child for social and economic decay, an urban museum inventorying all that has gone wrong with rust-belt cities after they peaked in the 1950s.

The invisible scars from the Great Rebellion have never healed. Former Detroit Mayor Coleman Young, who was elected seven years after the riot and was forced to deal with the city’s depleted resources, commented, “The riot put Detroit on the fast track to economic desolation, mugging the city and making off with incalculable value in jobs, corporate taxes, retail dollars and plain damn money.”

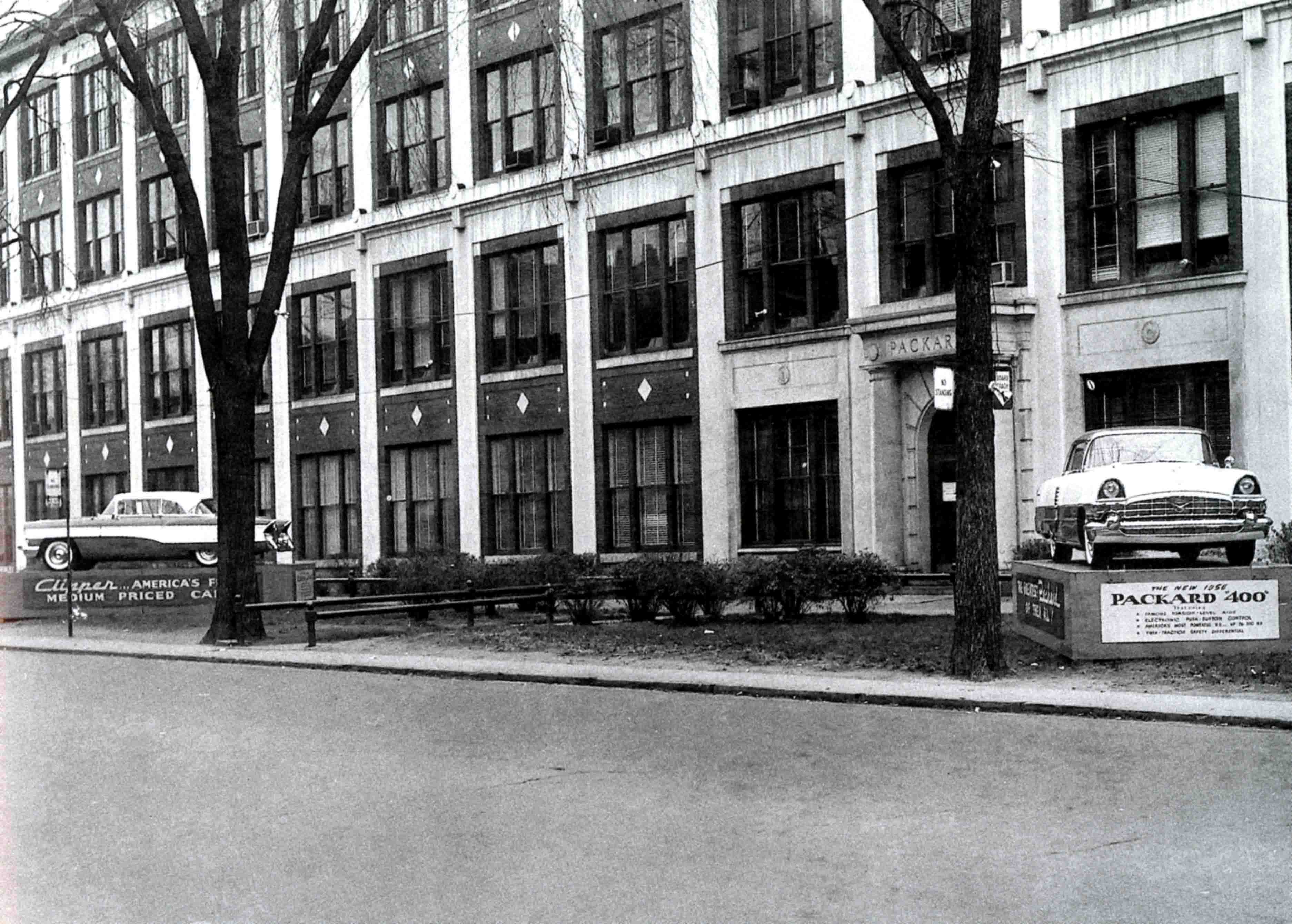

Packard today - An apparition from Detroit's heyday

Packard: Microcosm of Demise

The Long Arm of Packard - Begun in 1903, the complex would eventually

encompass some forty-seven buildings providing over 2.5 million square feet.

At its peak during WWII it employed 25,000 people. Note that unlike its modern

successors there were no parking lots; as few people drove cars to work because

they lived near by. Packard was thus the cornerstone of the community and when

it closed its doors for good in 1956 the devastating economic domino effect spelled

doom for the neighborhood. Examples like Packard could be found throughout Detroit.

A Packard emblem bespeaks of a time when the Motor City lion roared and

the world watched in awe. A visitor to Detroit once described the city as the

“sound of a hammer against a steel plate.” The cacophony of noise and energy was unrivaled by any city in the world. During WWII, Detroit couldn’t come close to filling the jobs offered. But as the decades clicked past, the roar of the lion began to fade. By the 1960s the auto industry, which had always been erratic, was no longer a cash cow of employment. The once mighty lion was being transformed into an anemic mouse.

The year 1950 was the high-water mark of prosperity for Detroit. In those days, Detroit was building one out of every two cars in the world. Now it builds one in every thousand. Detroit’s population spiked at 1.8 million and was king of the automotive world. As such, the city brought in millions of dollars each year to its economy as elite hotels like the Statler and Book-Cadillac were filled with out of town automotive conventioneers.

Now Detroit’s Depression-era high-rise hotels are either dust or derelicts. Conventions, which were always more monkey business than company business anyway, have found more appreciable climates. Las Vegas, which was a mere speck of dust when Detroit was king, now owns the convention world. Northern cities like Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland will never be able to distance themselves from the fact that for six months of the year the weather is cold, frozen and dreary.

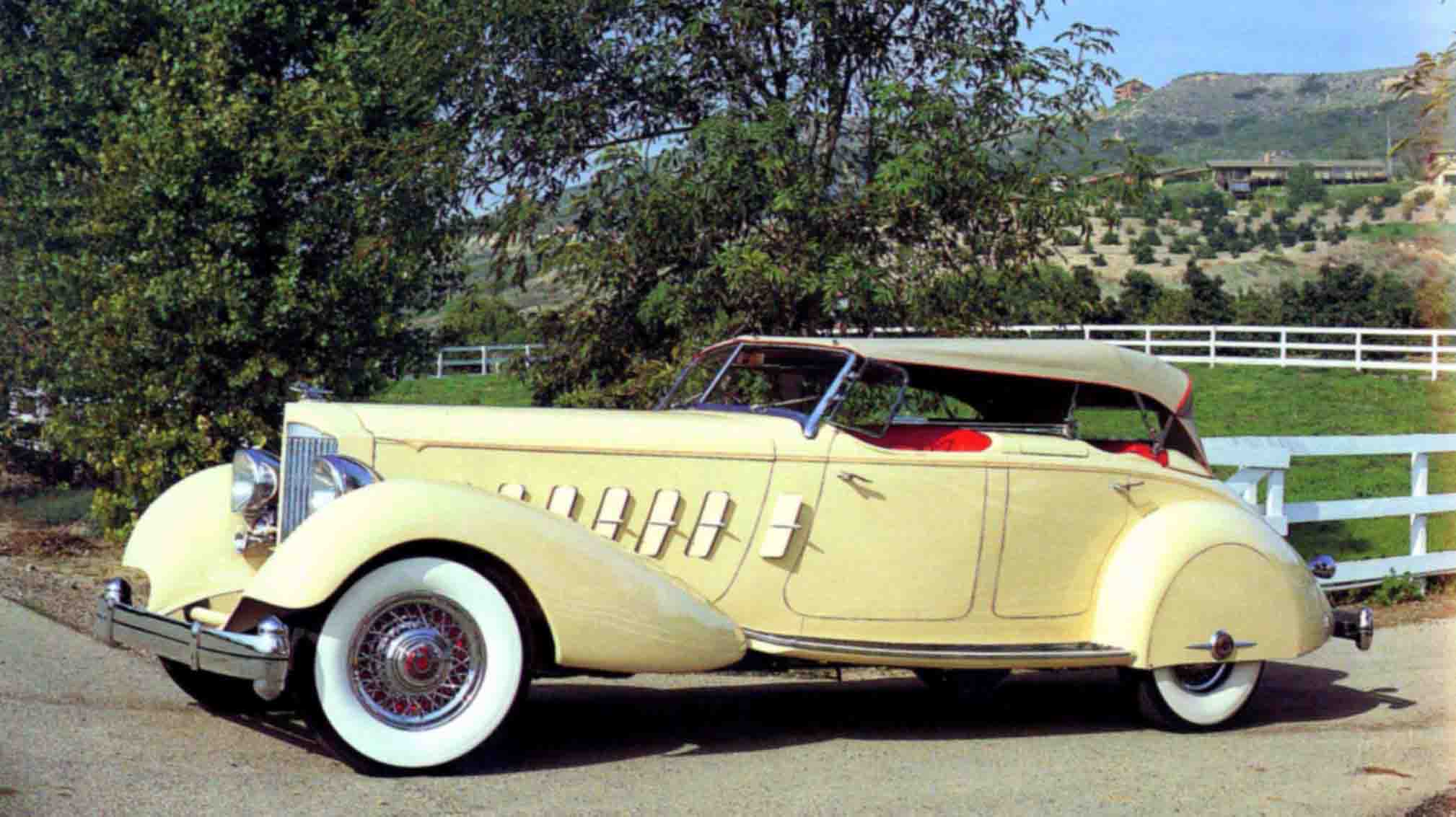

1934 Packard LeBaron

The legendary Packard Motor Company, brought to Detroit by millionaire

playboy Henry Joy from Ohio, will forever be remembered for its stunning

luxury cars of the 1920s and ‘30s. Still standing like an urban Titanic, it is

both a ghostly reminder of the ruthless competition in the automotive

industry and of a time when Detroit had something very special to be proud of.

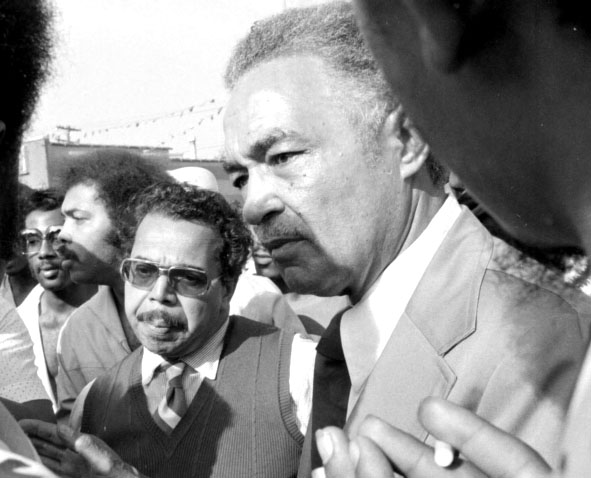

Young's Town

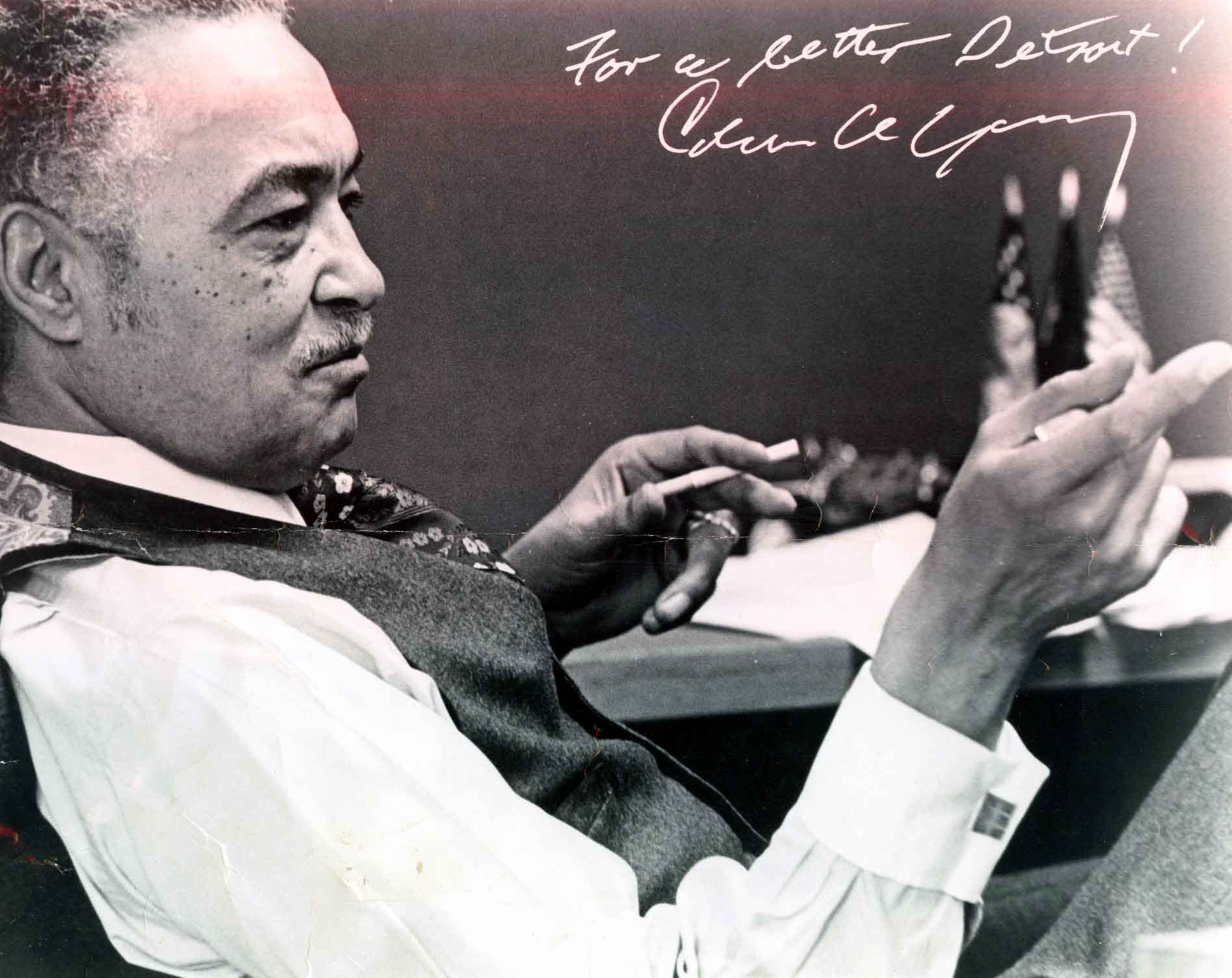

Detroit's fiery mayor Coleman Young.

He became the Great Black Hope.

Packard Motor Company - 1950s

Coleman Young would loom large over Detroit for a variety of reasons. It must be recalled that in the 1960s there were two and only two powerful black leaders. Martin Luther King on the right and Malcolm X on the left. Neither of these towering figures would survive to see the 1970s, leaving a cavernous vacuum in the black community. Then along came Coleman Young, a well-known street fighter who was afraid of no one. While it may have served as a poke in the eye to the white community, Young was a Moses to the leadership starved black community.

Young’s lifelong attitude was forged by poverty, perspiration and above all, the everlasting sting of prejudice.

Among the innumerable humiliating indignities in Young’s life was the Boblo boat incident. In 1931, the then 13 year old Young went on a field trip with his Boy Scout troop, of which he was the only black. Stopped at the dock before boarding, Young was told by a Boblo employee that he could not go because they didn’t allow blacks. It was a turning point for Young who would remember for the rest of his life the Boblo steamer pulling away from the dock with his friends on it. Henceforth he would view Whites with suspicion and distrust.

A lifetime of being kicked hard made Coleman Young suspicious of White intentions.

The humiliation incurred during the Boblo boat incident of 1931 was an affront that would sting for the rest of his life.

Young’s sharp tongue and left-leaning politics often are blamed for scaring away business and poisoning race relations. Yet research shows that the city’s economy had been in a tailspin for 20 years before Young took over in 1974 and during his tenure he was the most fiscally responsible of any mayor in the last 50 years. Some 400,000 people had high tailed it to the suburbs before the name Coleman Young was even a household name much less a symbol of the city’s decline.

Coleman Young, seen here as a state senator on a visit to Washington, took his hard earned street smarts learned as a child in Detroit’s Black Bottom and became one of the most formidable political wheeler-dealers the state has ever produced.

It was once said that a conversation with Young was both a history lesson and an exercise in critical thinking.

When Young was in high school, he became irate when a paper he wrote on Reconstruction was dropped from an A to a B. He criticized the text book for describing newly freed slaves as shiftless, lazy and incapable of governing themselves. “I just would not accept this picture of black people,” he later recalled. I didn’t have anything to base it on except that, of everybody I knew who was black, there wasn’t a goddamn soul that fit the description in the damn book.”

Young ran for mayor of Detroit in 1973 against former Detroit police commissioner John Nichols. Young represented a powerful minority voice and Nichols represented a symbol of the old days of white plutocracy. The winner would have the dubious distinction of taking over the most polarized city in the country, an heir to disaster.

A city plagued by overwhelming problems and little in the way of resources to solve them.

Young found a powerful ally in President Jimmy Carter. It was not uncommon, however, for the president to seek advice from the savvy mayor. Carter, who was from the Deep South, knew well the discrimination Young had faced in his life and treaded lightly when the two talked politics. Carter said of Young, "There is no other mayor closer to me than Coleman Young. He could have had a cabinet position had he wanted one but his preference was to stay in his own city.”

It must be said that all big cities in America were going through dramatic change during the early 1970s.

Newark received its first black mayor, Kenneth Gibson, in 1970. Ebullient blacks did cartwheels in the streets, blissfully unaware that Newark, like Detroit, had an unending list of problems to solve and little if any resources to do the job.

Old comrades referred to Young as “Big Time” growing up because he always had big ideas and wanted to change the world.

His critics had other names.

“I have to believe government shouldn’t be run by public opinion polls, Young once said. At some point, if you accept a position of leadership, you decide to proceed on what you think is right and let the people judge that at election time.”

The ghosts from Young's past seemed to always haunt him. He trusted few white people and when those few, Henry Ford II, Jimmy Carter, faded from the scene and were replaced by a less cooperative generation, Young was slowly painted into a corner he could not get out of and the city suffered as a result.

Former Michigan Supreme Court Justice Conrad Mallett said of Young, “He was in a very small class of politicians. He didn’t try to hide who he was, to sugarcoat it. He walked the walk. That made him a target for a lot of people who didn’t share his vision, and he took a lot of hits, but he didn’t whine. He just took it and got up and moved forward.”

The 1970s – Rock Bottom

The upheaval of the 1960's help set the stage for an even worse period in the city’s history. With businesses and citizens frantically leaving Detroit at a record rate, city coffers quickly emptied, leaving a barren desert of resources without even a mirage of hope. The result was predictable, a desperate city with desperate people. Detroit began a total emotional meltdown with a runaway murder rate which gave it a national black eye and the lingering moniker of the “Murder City.” Police commissioner John Nichols was forced to deal with the avalanche of anger, "The vast majority of these killings are not preventable by pure police methods. They occur in the home. If I knew why that happened, we could try to stop them. But some of the motivations in these killings stagger the imagination."

"The rage was there. The frustration was there. I think we see it. The more widespread use of narcotics today is an escape. Even the violence, including the shooting, is another release I think of this anger, this ongoing rage and frustration. For the moment, the black community has turned inward on itself."

- Coleman A. Young

Such was Detroit in 1974. The Big Three hadn’t laid off this many workers since the Eisenhower recession in 1958. One local newspaper captured the grim mood of the city when it sported a cartoon of Santa Claus clutching a layoff notice. One liquor store owner, who was in the heart of the riot area, lamented his fate, “The finer brands aren’t selling like they used to.” The worried store owner keeps six loaded guns in strategic positions around the store, “People are just standing around the neighborhood. Some are stealing a little and some are dealing a little. The country has gone to Hell.” Thus was the Detroit that Coleman Young inherited in 1974.

“There exists in the black community a feeling of worthlessness, that one black life doesn’t mean much, that life is cheap.” says a black Detroit psychiatrist. Coleman Young echoed those sentiments, "People who are hungry and unemployed commit crimes. People who have jobs and pride do not."

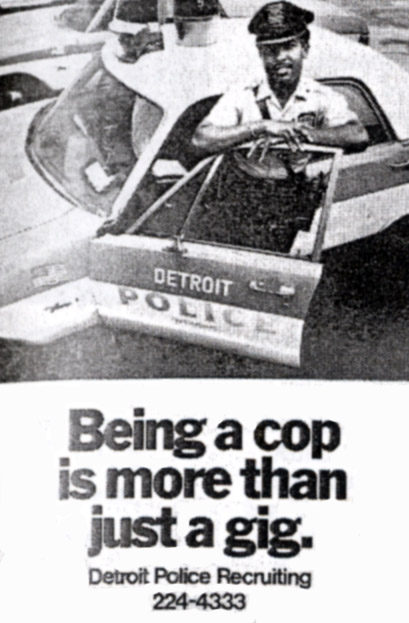

DPD recruiting poster - 1972

A concentrated effort was made during the Gribbs administration to increase the number of black police officers. Coleman Young would step up recruitment even further. Young was adamant that the police department be racially proportional to the city. In 1974 the city was approx. a 50/50 mix but the Detroit Police Department was still 85% white. The line had been drawn.

While many critics felt that Young's dismantling of the police department watered down its capabilities for years to come, like his predecessors he was sitting on a racial time bomb. University of Michigan professor Sidney Fine, an authority on Detroit, once stated, “To say he’s (Coleman Young) is responsible for the decline of Detroit is to ignore forces over which no one individual could have controlled.”

In the space of a short, tragic decade Detroit went from the automotive capital to the murder capital. Coleman Young, who would reign over the city for 20 years, had a luxury that few politicians had. He could speak his mind, often being brutally blunt, and not worry about getting re-elected. While this may have pleased his black constituents,

it enraged white suburbanites and would set the stage for a long, protracted Cold War between the city and suburbs.

As downtown shoppers went about their business, police warnings blared over the loudspeakers: “Walk in twos after dark, keep your hands on your purses, stay away from the alleys and have a merry Christmas.”

Replacing Despair with Hope....

This is the Nature of Americans

Father Cunningham

Eleanor Josaitis

The last chapter written out of the ashes of the Detroit riot would be authored by an unlikely duo, a suburban housewife and a Roman Catholic priest. There were many efforts to help the stricken city after the riot but none managed to carve out a more endearing legacy of altruism the way Focus:HOPE did.

In 1968, Focus:HOPE began paving a road of humanitarianism through the riot torn neighborhoods of Detroit, which for years after the riot were saturated with fear and hate. They began with a massive food distribution program and now feed some 50,000 mothers, children and seniors a month. To create opportunity, they started a machinist training program that has placed thousands of young Detroiters into good-paying jobs.

Eleanor Josaitis and Father William Cunningham were both greatly affected by the Selma march of 1965. Josaitis, by chance, happened to be watching “Judgment at Nuremberg” when the movie was interrupted by footage of Alabama state troopers pummeling peaceful civil rights marchers. For her it was an awakening, “I kept thinking, what would I have done if I had lived in Nazi Germany? Would I have pretended that I didn’t see anything? Then what am I doing about what’s going on in this country?” Cunningham and Josaitis were a conscience looking for a cause.

Fate would provide that for them in July of 1967.

Josaitis moved from the suburbs to Detroit shortly after the riot to establish Focus:HOPE, despite the fact that her family thought she was losing her grip on reality. She has lived in Detroit ever since. As a constant reminder that her work is never finished she frequently takes a different way home, making mental notes of the city’s social conditions as she drives.

In the months after the riot, Cunningham brought the Black Panthers and the KKK together and proceeded to lecture them at length about racial intolerance. Apparently his points were well-taken, for the two groups in turn began preaching an anti-hate campaign across the city.

The fearless Father Cunningham took on all of life’s challenges, including a charity boxing match against heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali in 1971. His specialty, however, was fighting poverty and prejudice in post riot Detroit. Cunningham’s bout with cancer in 1997 was one battle he would not win but his legacy of salvaged souls throughout the city is testament to a man who was the embodiment of hope. Former Detroit mayor and close ally Coleman Young said of Cunningham: “He combined a compassion with vision, with energy and integrity. That’s a rare combination. I have never seen the likes of someone like him.”

The Good Shepherd

When the down and out of Detroit’s homeless garrisons

find themselves at the end of the line, when there is no place

left to go and no one else to turn to, there is always Mother

Waddles. Like the Good Shepherd tending her wandering flock,

Mother Charleszetta Waddles offers a rare but constant sanctuary.

She has been feeding, clothing and sheltering Detroit’s

downtrodden for forty years.

Mother Waddles, herself an ordained Pentecostal minister,

became Detroit’s patron saint for those in distress. Her one

woman assault on Detroit’s impoverished is the DNA that true

heroes are made of. She has never asked for, nor has she

ever received, any money from any tier of the government,

a fact she is perpetually proud of. While her coffers always

flirted with exhaustion, her formidable skills and magnetic

charm seem to draw charitable works from well endowed

community leaders.

While Waddles does not accept money from those few

who can pay, she does expect an attentive ear on Sunday

morning while she preaches to her flock. Among Waddles

diverse congregation can be found an alphabet soup of

destitution: chronic alcoholics from Skid Row, junkies,

current and former prostitutes, panhandlers and confidence

men. To her flock she preaches perseverance and enlightenment.

To society, she preaches the helping hand of humanity,

“We’re trying to show what the church could mean to the

world if it lived by what it preached. We (Christians) got a

long way to go. We think prayers get answered by a far-away God.

We think we can pray to God without being involved. That’s not true.

We don’t realize we have to answer prayers as well as pray. We must have prayer and prayers don’t get answered unless we become

involved in the business of loving each other.”

For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat...

I was a stranger and you invited me in...

I needed clothes and you clothed me...

- Matthew 25:35-36

Detroit’s Mother Waddles: “I read the Bible. It didn’t just say go to church. It said do something.”

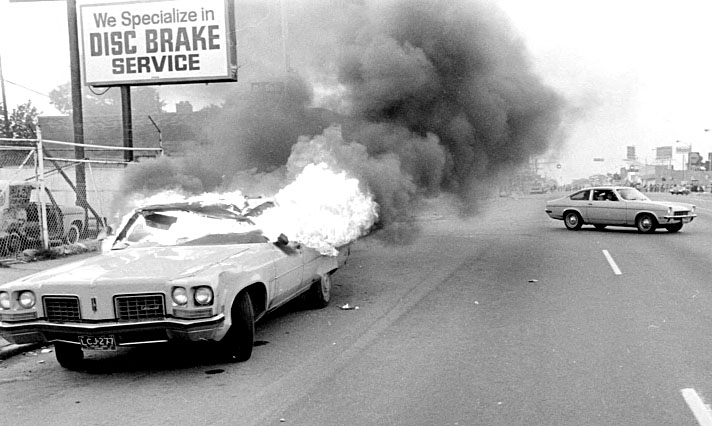

The Livernois Incident: Another Near Miss

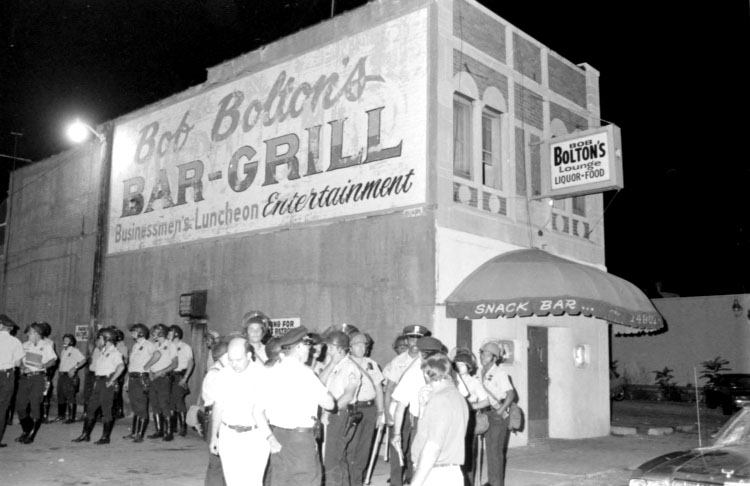

By the summer of 1975, now a year and a half into new Mayor Coleman Young's first term, the city was about to

nose dive into even deeper and yet more troubled waters. On a sweltering July day in 1975, Bolton's Bar off

Livernois was busy keeping its white clientele cool. With the continual racial fallout from the '67 riot 8 years previous still spreading like a cancer, most of the old mom and pop stores had long since pulled out and re-anchored in the suburbs. But not Andrew Chinarian, the bars owner, who had ignored the tidal wave of white flight over the depressive decade of the 70s to man the last stand of whites in Old Detroit.

On July 28th, Chinarian exited the bar only to find several black youths tampering with a car in the parking lot.

Chinarian fired a shot at 18-year old Obie Wynn, striking him in the back of the head. Wynn died 9 hrs later.

Chinarian claimed he was only attempting to fire a warning shot over Wynn's head. The triggering point came when Chinarian was taken into custody and then released on a paltry $500 bond. The neighborhood at Livernois & 7 Mile exploded. Bolton's Bar was ransacked and set on fire.

Obie Wynn

Andrew Chinarian

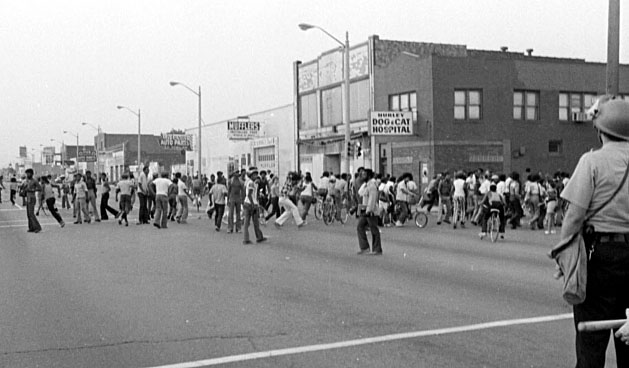

In what was to become known as the Livernois Incident, Detroit narrowly avoided another major riot. Only police restraint and citizen groups preaching patience prevented another calamity.

Alerted to the situation, Mayor Coleman Young sped to the scene only to find Livernois awash from stem to stern with angry blacks attempting to turn a riot. Young ordered all black officers into the area as a visual trump card. Knowing full and well what happened to his predecessors who mounted the hood of a car during the '67 riot (they were stoned), Young mounted the hood and spoke as harshly as he dared to the volitile protestors. He reassured the crowd that Chinarian had been re-arrested and his bond hiked to $25,000. Young also made it clear that although he

was on their side, he wasn't going to allow them to burn the town down.

Black mobs took over the streets, starting fires and breaking windows. A 54-year old baker named Mario Pysko who worked nearby was pulled from his car and beaten to death. Pysko, who hailed from Poland, was a survivor of a Nazi concentration camp.

Mario Pysko

From the Ashes - A Renaissance

Mayor Coleman Young was soon to find out that he had trouble on more than one front. After the crowd had dispersed, a

Detroit police cruiser with three unidentified white officers pulled up and threw a smoke bomb under Young's car. Young, in tandem with a sympathetic police inspector, began a high speed pursuit but could not catch up to the high powered cruiser.

Meanwhile, the angry crown had re-ignited and attempted to pull Chinarian from the bar. Chinarian was saved by Detroit police but further down Livernois, 54-year old Mario Pysko was not so fortunate. The Polish baker was on his way home from work when rioters pulled him from his car and beat him to death.

Detroit Mayor Coleman Young, seen here at the Livernois incident, managed to stave off a riot by quelling an angry crowd. It was a narrow escape at a time when Detroit was at

rock bottom.

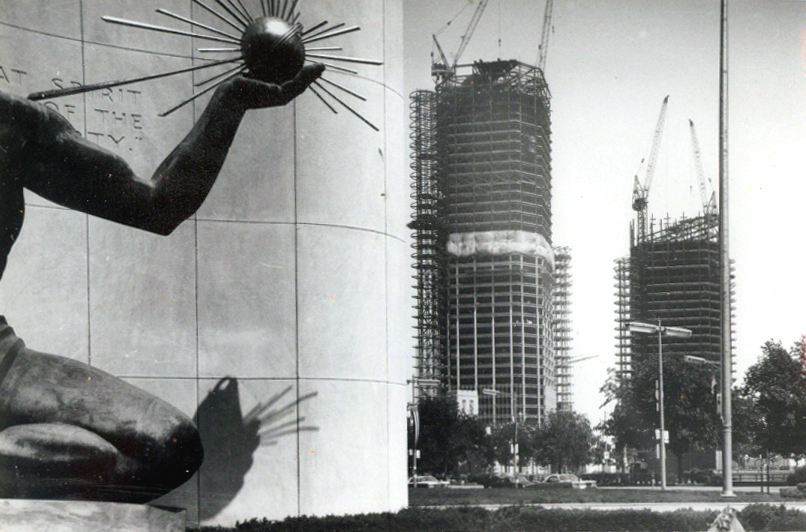

1973 - After clearing the accumulation of junkyards, abandoned warehouses and deserted parking lots on the river front, the foundation for the Renaissance Center is ready to be laid down. Much like the city's motto, "We will rise from the ashes," the "RenCen" was meant to be a cornerstone for a rebirth, not an all encompassing dynamo that would single handedly raise Detroit back to its greatness of the 40s but rather to ignite, as its name suggests, a revival.

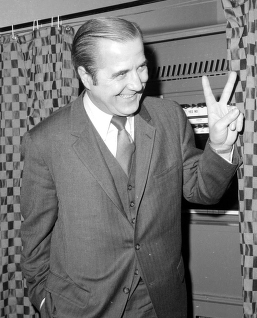

As factories and jobs disappeared, people left the city. The city’s tax revenue base withered. The tax loss led to cutbacks and non-repair of basic services. The reduction of infrastructure led to more factories vanishing, continuing a vicious circle of attrition that had a strangle hold on the city. Detroit was going backwards in time. As decades of civic sloth laid waste to the city's greatness, the tipping point in time had come for the city to either sink or swim. As the vultures circled over the city, Mayor Roman Gribbs held high hopes that the RenCen would be the anchor of a "complete rebuilding of the waterfront from bridge to bride." This enormous task would be laid on the shoulders of the most prominent name in Detroit, the grandson of Henry Ford, Henry Ford II, to pioneer a comeback.

Henry Ford II, known as the Duece, was the driving force behind the Renaissance Center. A man of considerable reputation, when he talked about how Detroit's "gasoline aristocracy" that had originally made a name for themselves in Detroit should show a commitment to helping the city instead of abandoning it, big people listened.

Post riot mayor Roman Gribbs (1970-74) would hope and pray for peace but it would elude him and the city for decades to come.

The city’s “office population,” which had taken on the appearance of an Olympic sprinter heading out of town, had all but disappeared. What had been the city’s financial center by day was a graveyard at night. The echo of the catastrophic ’67 riot seemed to bounce off its once glistening and now empty sky scrapers. RenCen architect John Portman offered his assessment, "You can't make people come into the city. You have to create the circumstances that will attract them. Cities have the image of being unsafe places. To reverse that, we have to give people city environments where they feel safe."

Initial critics have called the Renaissance Center a Noah’s Ark for the white middle class. There is evidence to support their claim. The formidable abutments that shielded the RenCen from Jefferson Avenue gave the complex a fortress like complexion, making it nearly impenetrable by undesirables. Still others argued that the massive RenCen would poach tenants from nearby office buildings, essentially borrowing from Peter to pay Paul. As a result, the city was forced to give tax breaks to keep those entities solvent.

Monuments of Hope – The Spirit of Detroit statue, the old symbol of hope, passes the torch of promise to the neighboring Renaissance Center.

Detroit was not dubbed the Motor City because of its charm and never attempted to put on airs like many rival cities. However, Detroit can rightfully boast of two accomplishments that her rivals cannot match. Detroit put the world on wheels and more than any other city helped America win WWII.

The sparkling new Renaissance Center towers over Detroit like the Emerald City of Oz. The 'Ren-Cen' gave the city a much needed facelift and continues to this day to be the symbol of a city attempting to reinvent itself and regain its once illustrious and hard fought world prominence.

1885

1980s Today

1980s Today

The former home of Detroit lumber baron Lucien Moore accurately depicts Detroit's last

100 years. From prominence to privation to promise, Detroit has gone the cycle.

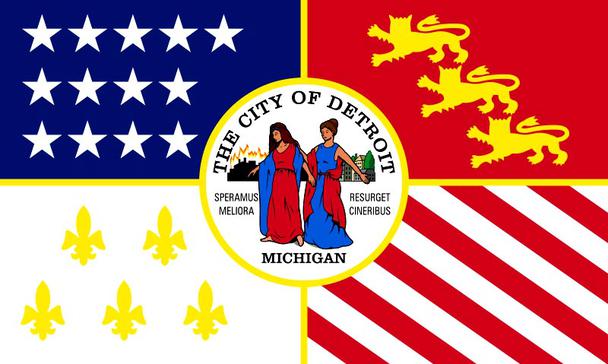

Five Fleurs-de-lis on a white background. Emblematic of the French House of Bourbon

which was responsible for the founding of Detroit in 1701.

Thirteen stars (upper hoist) represent American occupation of city from 1796-1812.

Three heraldic gold Lions on a red background. Emblematic of the British rule over Detroit from 1760 to 1796. (King George III)

Thirteen stripes (lower fly) represent American

reoccupation of city from 1813 to present day (after British occupation during war of 1812.)

The Seal of the City of Detroit, born out of the fire which destroyed the city in 1805,

would prove to be an iconic depiction for the next 200 years. The women on the left, who represents Sorrow, grieves for the burning city behind her. The women on the right, who represents Hope, offers consolation and a vision for a brighter tomorrow.

Father Gabriel Richard, a Roman Catholic Priest who witnessed the 1805 fire, offered the rational which would become the city's motto:

Speramus Meliora: “We hope for better things"

Resurget Cineribus: "it will arise from the ashes"

An appropriate moniker for the great fire of 1805 and an eerie portent for the

great fire of 1967.

City of Detroit Seal

Post-Riot Detroit

Detroit Mayor Coleman Young

Inaugural speech - 1974