1943 - A race riot there will be

Detroit Riot 1943

The summer of 1943 found the United States embroiled in the worst war in world history and the industrial might of Detroit was playing an integral part in winning it. Common during times of war, domestic hatreds and tensions grip entire communities, bringing out the best and worst even among allies. At a time when Americans were pulling together to defeat its enemies, societal problems of long standing chose a bad time to rear its ugly head in Detroit.

In June of 1943 Detroit suffered one of the worst race riots in the country’s history, forcing America to take a long, hard introspective look at itself. Analysts concluded there was no one specific cause to the disorder but rather a multitude of causes that had been a long time in the making. It was, if viewed on the whole, just pieces of a puzzle.

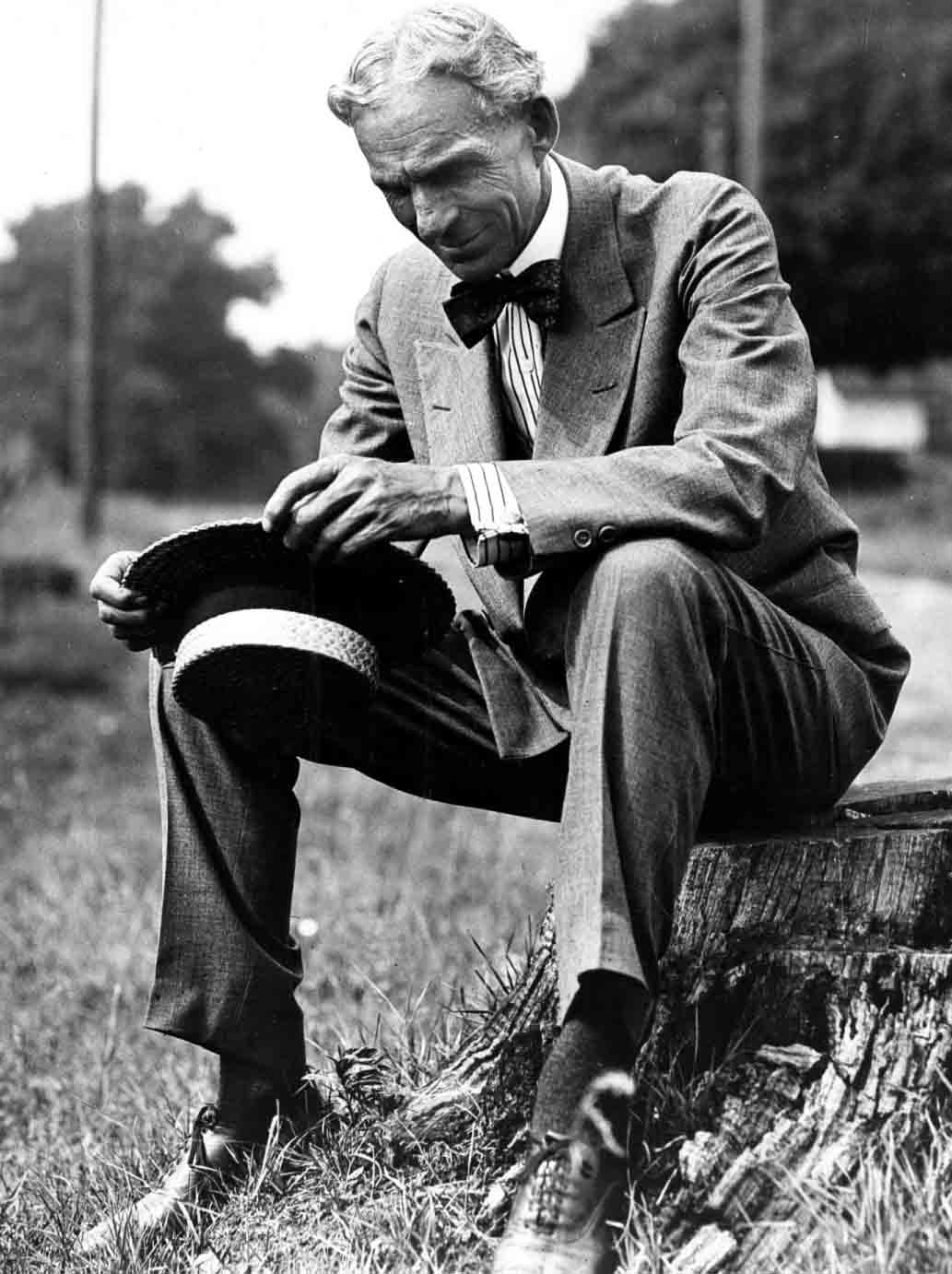

"Because we got Henry!"

In the early 1900's, Detroit civic leader Homer Warren, who was renowned for his silk tongued sales pitches that he often lobbed at prospective out of town investors, routinely centered his arguments on Detroit’s most famous face. “Detroit is going to grow and grow. We’re going to have a million people within a few years. And do you know why? Because we got Henry Ford. He’s figured out a new manufacturing method – the assembly line. He’s gonna standardize and mass produce his car faster and cheaper than any of his competitors. There’s going to be the biggest damn explosion of heavy manufacturing this country has ever known and Detroit’s going to be right in the middle of it. And do you know why? Because we got Henry!”

Henry was the first to employ thousands of blacks when everyone else was reluctant to hire even one. His $5 day would also be the catalyst for the largest demographic change in American history. Ford taught successive generations the time-honored American principles of perseverance and sacrifice. The road to success meant outworking the other fellow and paying your dues. Henry reveled in sending shock waves through the corporate world. Endowed with only a fourth grade education, Henry felt ill at ease around the Ivy League blue bloods of industry and no doubt took great satisfaction in showing them up, a feat which he accomplished with regularity.

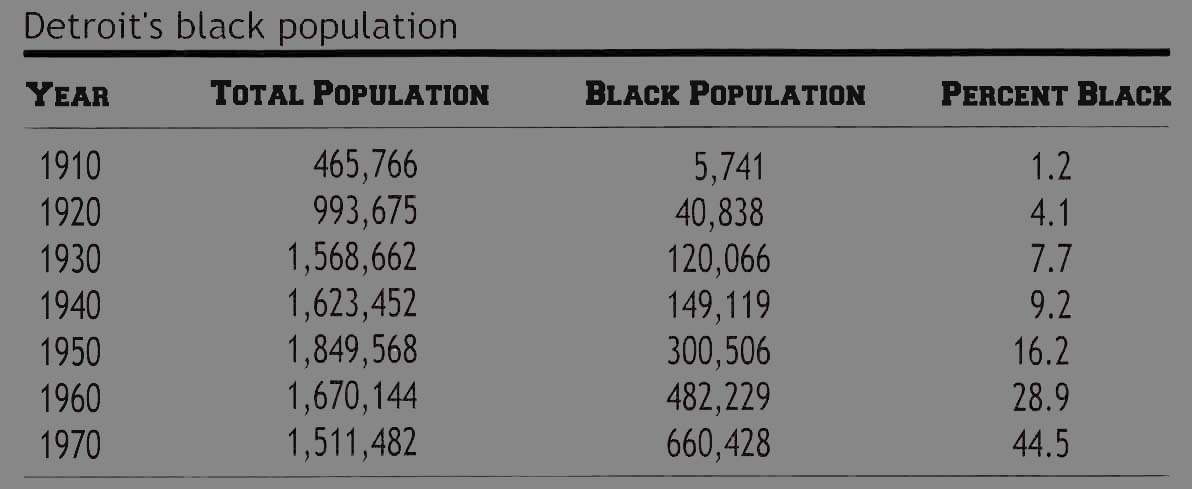

The Great Black Migration 1910 - 1930

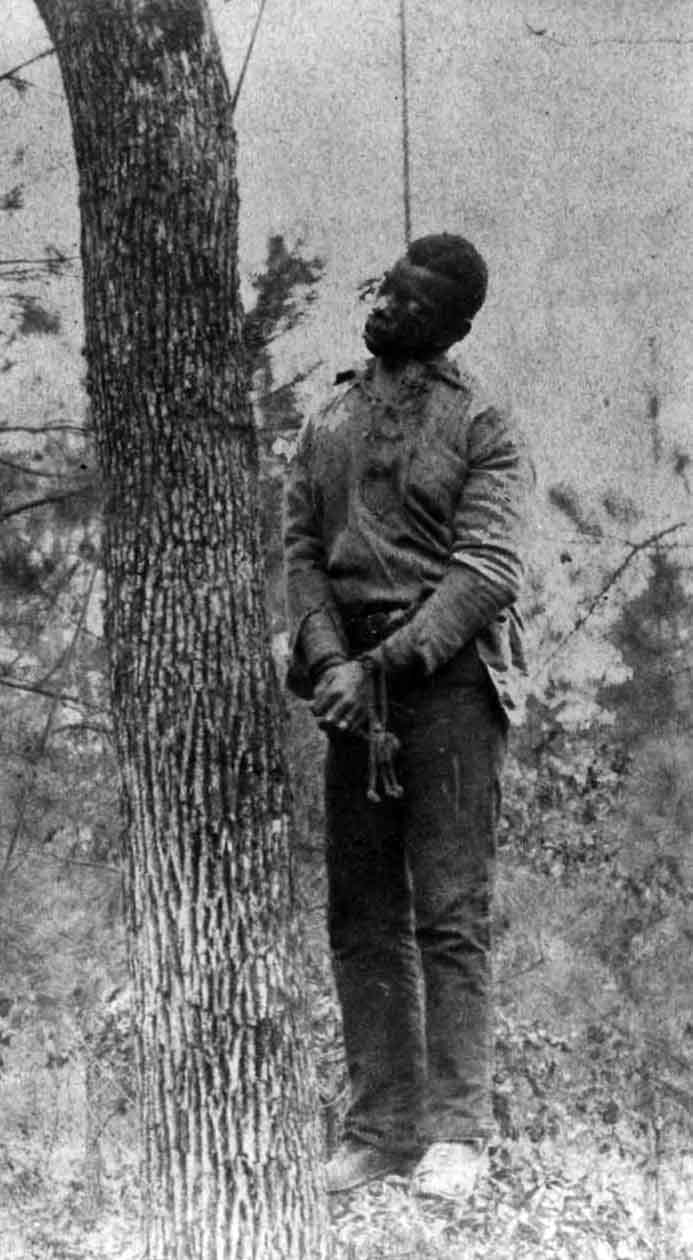

With the final withdrawal of Union troops in 1877, Reconstruction had come to an abrupt end, as did the hopes and aspirations of free Southern blacks. The Democratic Party, in those days referred to as the party of white supremacy, slowly returned to power throughout the South. The ghostly apparition of the Old Confederacy had re-appeared and with it the continuation of the black agony.

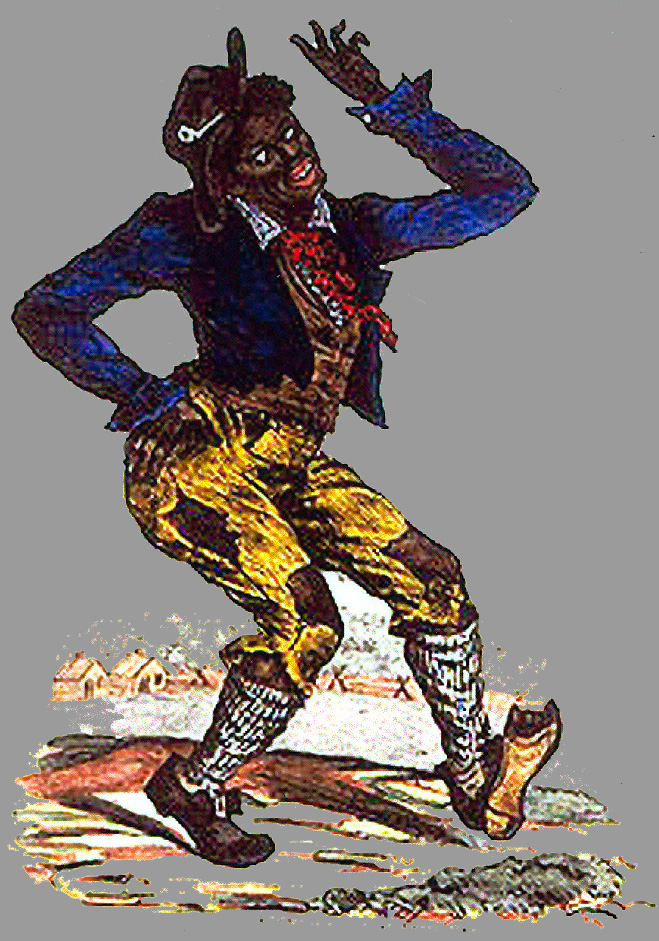

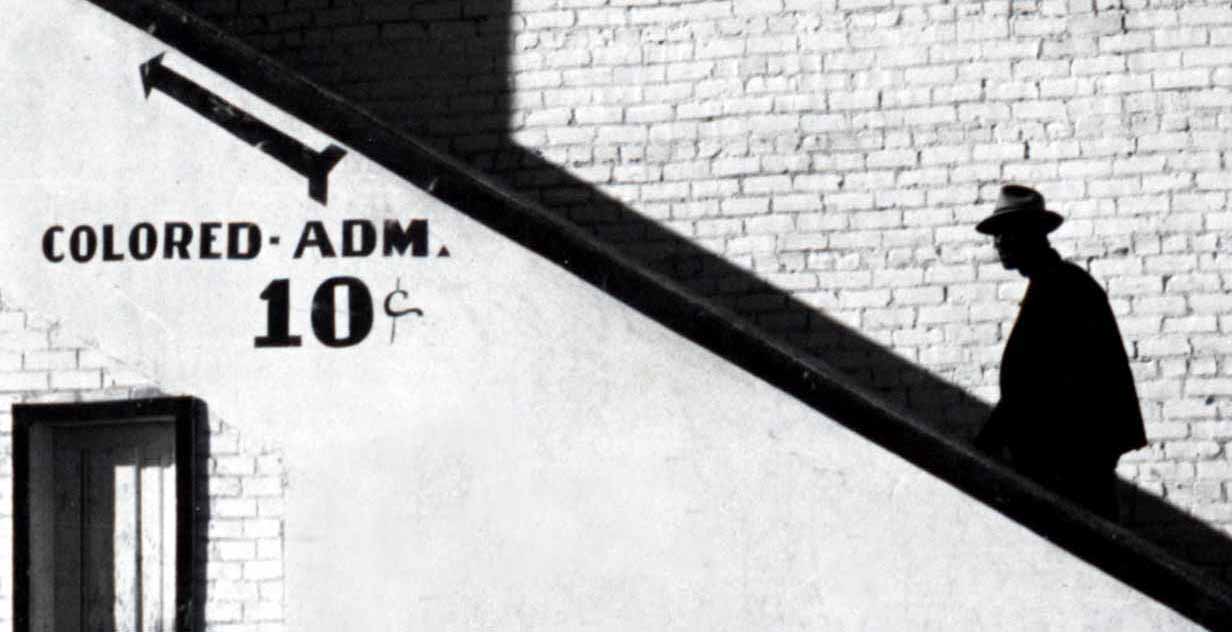

The term Jim Crow originally referred to a character from an old minstrel show dating back to pre Civil War days. It was a white man dressed in blackface performing a mocking rendition about black life. It proved immensely popular with whites.

In post Civil War days Jim Crow came to refer to local laws and customs designed to enforce segregation and prevent blacks from gaining any political, social or economic power. While the North made some inroads towards desegregation, the Jim Crow mentality persevered throughout the country. Its hotbed of course, was the South.

This concept was further buttressed by the 1896 Supreme Court decision of Plessy v Ferguson which declared that separate but equal facilities were constitutional. Referred to as Jim Crow laws, they were enforced until President Lyndon Johnson ended the indignity by signing the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965.

Jumpin Jim Crow

Jumpin Jim Crow lyrics

Come listen all you galls and boys I's jist from Tuckyhoe,

I'm going to sing a little song, my name's Jim Crow,

Weel about and turn about and do jis so,

Eb'ry time I weel about and jump Jim Crow.

Oh I'm a roarer on de fiddle, and down in old Virginny,

They say I play de skyentific like Massa Pagannini.

Weel about and turn about and do jis so,

Eb'ry time I weel about and jump Jim Crow.

As time went on it became more and more apparent that there was little opportunity to be found in the South for blacks and that their newfound freedom was mostly illusionary. Since blacks owned no land, did not control government or provide jobs, they wound up working for the very people who once owned them. As sharecroppers, they earned a mere pittance and were essentially nothing more than freed slaves.

Older blacks tended to take it in stride; the agricultural life was all they knew. Young blacks, however, yearned for something better and believed the seeds of opportunity would germinate for them in the North.

Reasons for migrating North

Southern blacks who eventually migrated north during the 1900's wished to leave the misery they experienced in the South behind for good. It was this same misery that brought about the formation of the blues which became the subject of many of their songs. The blues were a combination of dreams unfulfilled, biblical belief, spiritual ebullition and present/past agonies and aspirations. Whether it be prisoners on the chain gang or prisoners to the cotton field, the blues helped express pent-up feelings and vent a multitude of hostile frustrations to help discouraged blacks make it through yet another day.

Blues legend John Lee Hooker originally hailed from the cotton fields of Mississippi. Like many southern blacks, he made his way to Detroit during WWII. Hooker had joined the army during the war but was let go when it was

discovered he was underage. Adrift in Detroit, the veteran bluesmen found a new home in the Hastings Street clubs where his southern blues music struck a cord. His eerie Mississippi moans and throaty wails simply couldn’t be duplicated. Hooker would call Detroit his home for the next 27 years, witnessing dramatic social changes first hand.

"I was happy in Detroit because I loved the music.

John Lee Hooker

Southern blacks entering Detroit found a city totally unprepared to accommodate them. The most immediate problem, one that would haunt the city indefinitely, was housing. The housing shortage was acute before the Great Migration and would get worse for decades thereafter. Blacks were caught in the cross-hairs of redlining, a practice of bankers and real estate agencies who would draw a red line around areas on the local map where they refused to allow blacks in. This left Black Bottom, an enclave of dilapidated wooden houses that should have been torn down before they fell down. Unable to buy, blacks were forced to rent from slum lords. Because the rent was two or three times higher than normal they were forced to take on boarders to make ends meet, creating terrible overcrowding.

There were some niceties associated with working in the auto factories. There was little wage discrimination between blacks and whites. The difference came in job stature and promotion. Blacks were given the most dangerous and health hazardous jobs such as iron pouring, furnace tending or spraying paint. While it is true whites often did the same work, they were frequently promoted despite having considerably less time in. This mentality was confirmed by a plant manager, “Negroes can’t work on the presses. We brought the Negro to this plant to do the dirty, hard unskilled work. If we let him rise, all of them will want better jobs.” To his credit the manager admitted this was unfair, “But we can’t try any experiments here. We are competing with other automobile firms and we’ve got to keep our men satisfied to keep up the competitive pace. Personally I’d like to help them, but what can I do?”

“When I die, bury me in Detroit”

Southern blacks had long considered Detroit the Promised Land and Henry Ford a Moses type character who led them out of bondage. As far back as the Civil War, Detroit was a major terminal of the fabled Underground Railroad. In the 1910's, Ford’s $5 day and the U.S. entry into WWI proved to be the parting of the Red Sea and at the end of it was the salvation of Detroit. Southern blacks held an indelible scorn for the Deep South and the Jim Crow mentality that prevailed and humiliated. Detroit represented a cultural rebirth. No longer would they have to remove their cap when talking to a white person. No longer would they have to step off the sidewalk to allow a white to pass by unimpeded. The euphoric liberation that the North provided invoked a common request, “When I die, bury me in Detroit.”

“I’m goin to get me a job, up there in Mr. Ford’s place,

Blacks earned more money than they had ever dreamed of in Detroit’s auto industry, but was it worth the price? Young men grew old long before their time because of the physical toll and hazards they encountered at work.

Southern blacks were not the only entity envious of a high paying blue-collar job. A veritable tidal wave of white Southerners also flooded into Detroit. Over 500,000 migrants arrived between June of 1940 and June of 1943 alone. Approximately 50,000 were black. The rest were a hodgepodge of poor white Appalachians, unsuccessful farmers, Baptists, Methodists and others. It was Detroit’s version of The Grapes of Wrath.

Detroit had run the economic gamut over the decades. From a buzzing metropolis of the WWI era flaunting its automotive prominence, to an anemic invalid of the Great Depression in the 1930's, and then back again to a bee hive of activity which WWII dictated. With well-paying jobs in excess, the Motor City offered unheard of opportunities. This point resonated throughout the South where poor sharecropping blacks were becoming expendable due to modern advances in farm machinery and the ravages of the boll weevil.

Northern whites also grew indignant about their new neighbors. They did not want to live near blacks nor did they want the labor competition which would certainly appear after WWII ended and the multitude of military production jobs began to dry up.

Even before the arrival of the southern migrants, Detroit was a checkerboard of ethnicities which included Germans, Irish, Italians, Maltese and various Slavs (a very large Polish contingent), all of whom gravitated toward their own sections of the city. Few people really considered themselves Detroiters; ethnicity dictated who you were and where you lived. Detroit had not yet learned how to be a city. Add to the influx of Southerners a few demagogic and communist agitators and you have the most heterogeneous cast of characters in the country. Even as Detroit basked in the light of prosperity and national adulation for leading the way in beating fascism, sinister forces were at work which would bring the city down. Detroit was saturated with characters that had an ax to grind. This volatile mix would put Detroit on a war footing of its own.

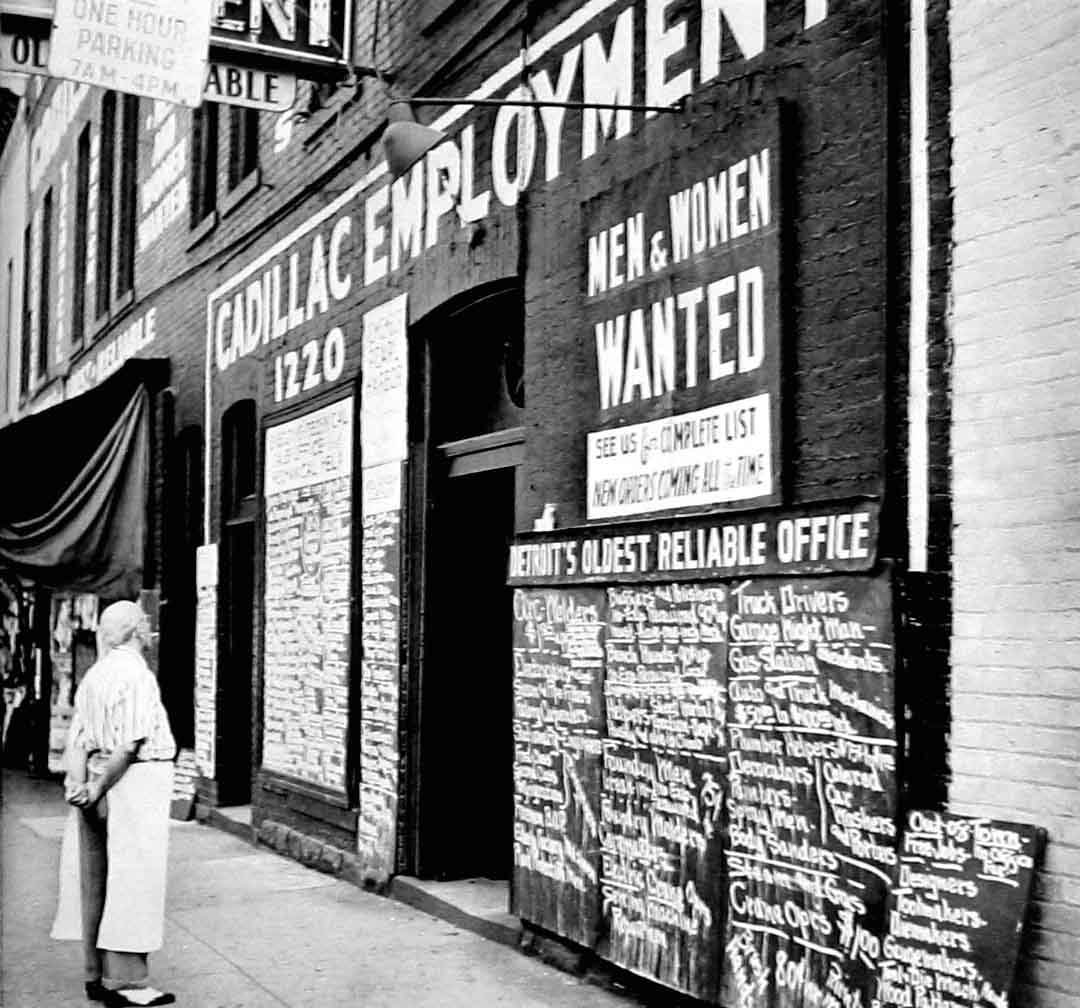

Wartime Detroit was awash with good paying jobs, as this puzzled shop keeper on the left attests to. It was also saturated with a host of dysfunctional groups, many far from home, all antagonistic towards each other.

Detroit was bearing the brunt of the war production for the country, cranking out a staggering 1/3 of the military equipment

being used to fight the fight. But it came at a price. Detroiters, worn and frazzled from endless production work, were at the breaking point.

Detroit’s racial situation had become so precarious and so pronounced that in August of 1942, ten months before the notorious riot, LIFE magazine wrote a caustic article entitled “Detroit is Dynamite” admonishing the city at length for its poisonous racial atmosphere and predicting the city would riot:

Few people doubt Detroit can do this colossal job.

It has the machines, the factories, the know-how as no other city in the world has them. If machines could win the war, Detroit would have nothing to worry about. But it takes people to run machines and too many of the people of Detroit are confused, embittered and distracted by factional groups that are fighting each other harder that they are willing to fight Hitler. Detroit can either blow up Hitler or it can blow up the U.S.

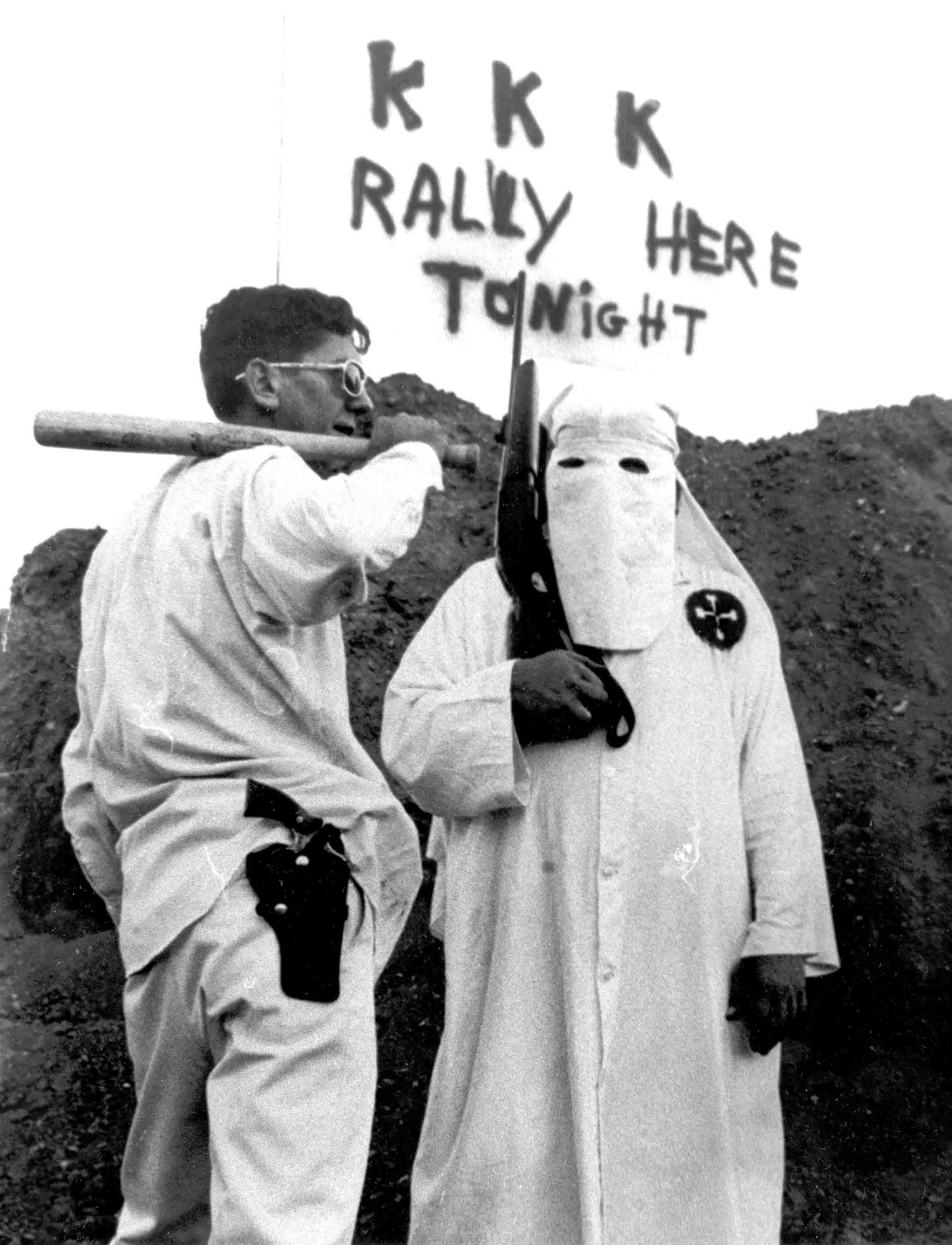

From the ashes of the Confederate army came this social club that began terrorizing blacks to keep them from exercising their new constitutional rights. Their overwhelming success caught the eye of the federal government which repeatedly attempted to squash them, thus causing a cyclical existence.

By the turn of the century the KKK virtually ceased to exist, only to rekindle in the 1920's to the tune of four million members. It was at this time that they added to their list of adversaries Jews, Catholics, foreigners and organized labor. By the time of the Great Depression they faded away again, only to reemerge one last time during the civil rights heyday of the 1960's. The magazine New Republic estimated that Michigan held as many as 875,000 Klan members, more than any other state.

Black Legion - Born out of the decomposition of the KKK, Detroit had become the stronghold for a shadowy fascist group of night riders known as the Black Legion. Originally formed to procure jobs for southern whites during the chaotic years of the Depression, their hit list included but was not limited to Blacks, Jews, Catholics and unions.

Although somewhat comical in appearance, the Black Legion was every bit as vicious as the KKK and even more feared. It was publicly known they had penetrated the ranks of big business and government. As a result few people dared testify against the Legion for fear of their transparent agents. Their secretive nature was reinforced by a code, “to be torn limb from limb and scattered to the carrion” if they betrayed any secrets.

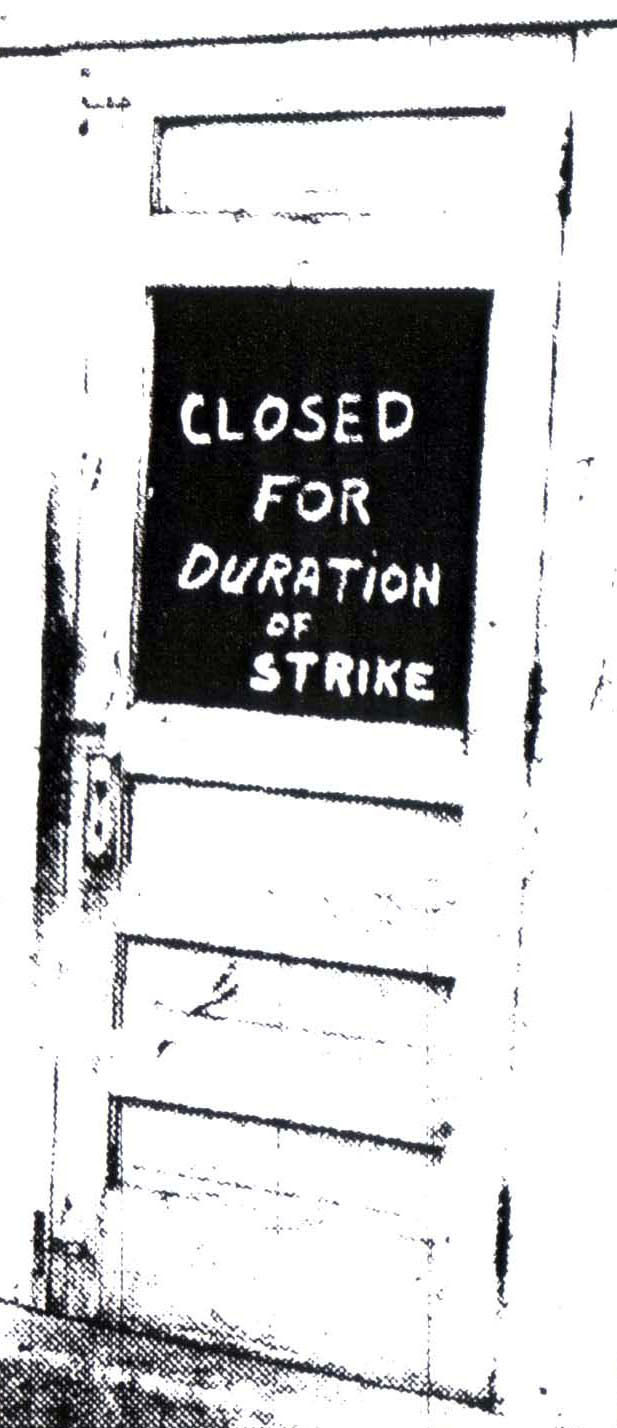

April 1941 - (Above, left) Thousands of southern blacks were employed at Ford’s River Rouge Complex. In 1941 the UAW waged a strike at the Rouge. Whites walked off the job but blacks stayed behind. Many blacks felt a loyalty to “Uncle Henry.” The two groups clashed on numerous occasions in barbaric fashion.

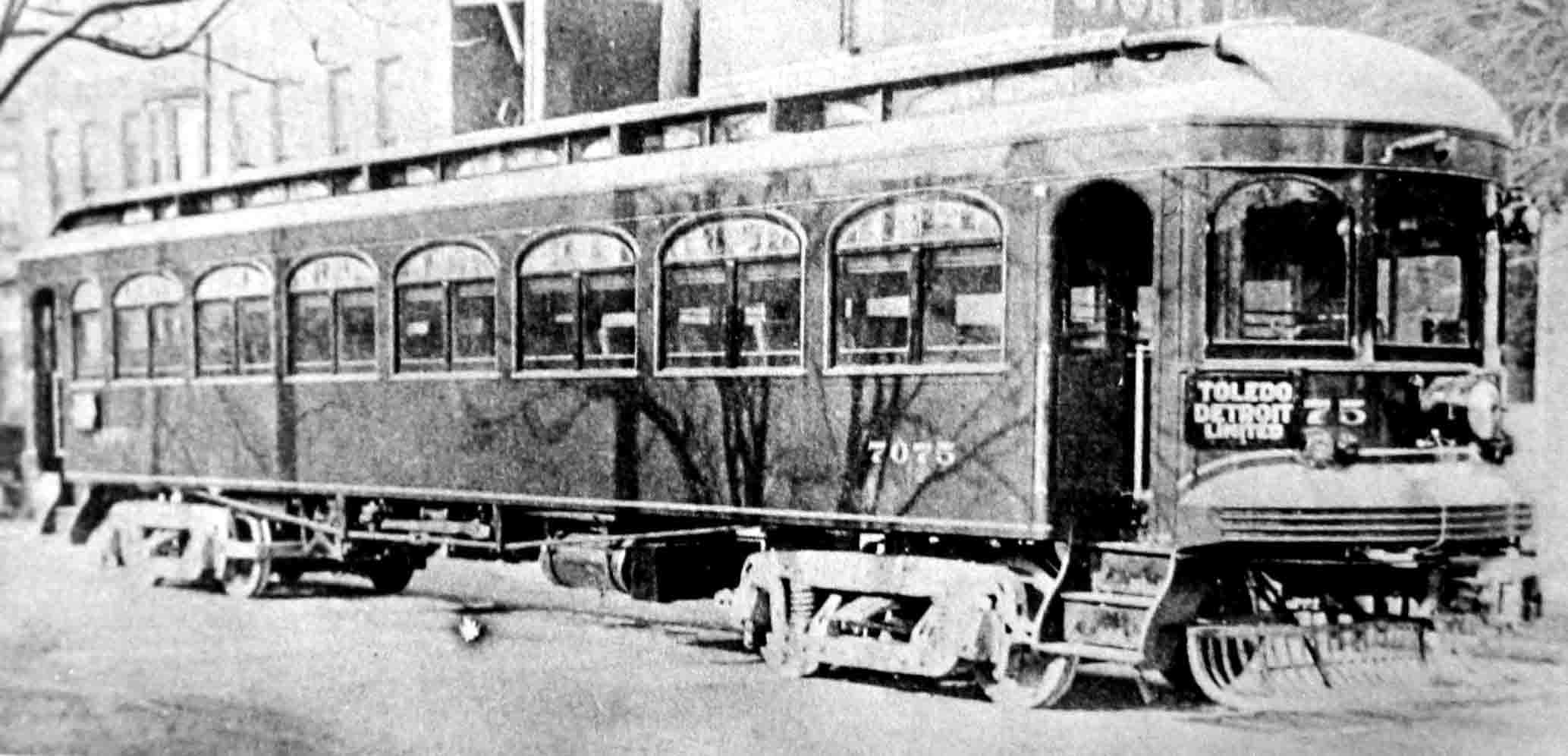

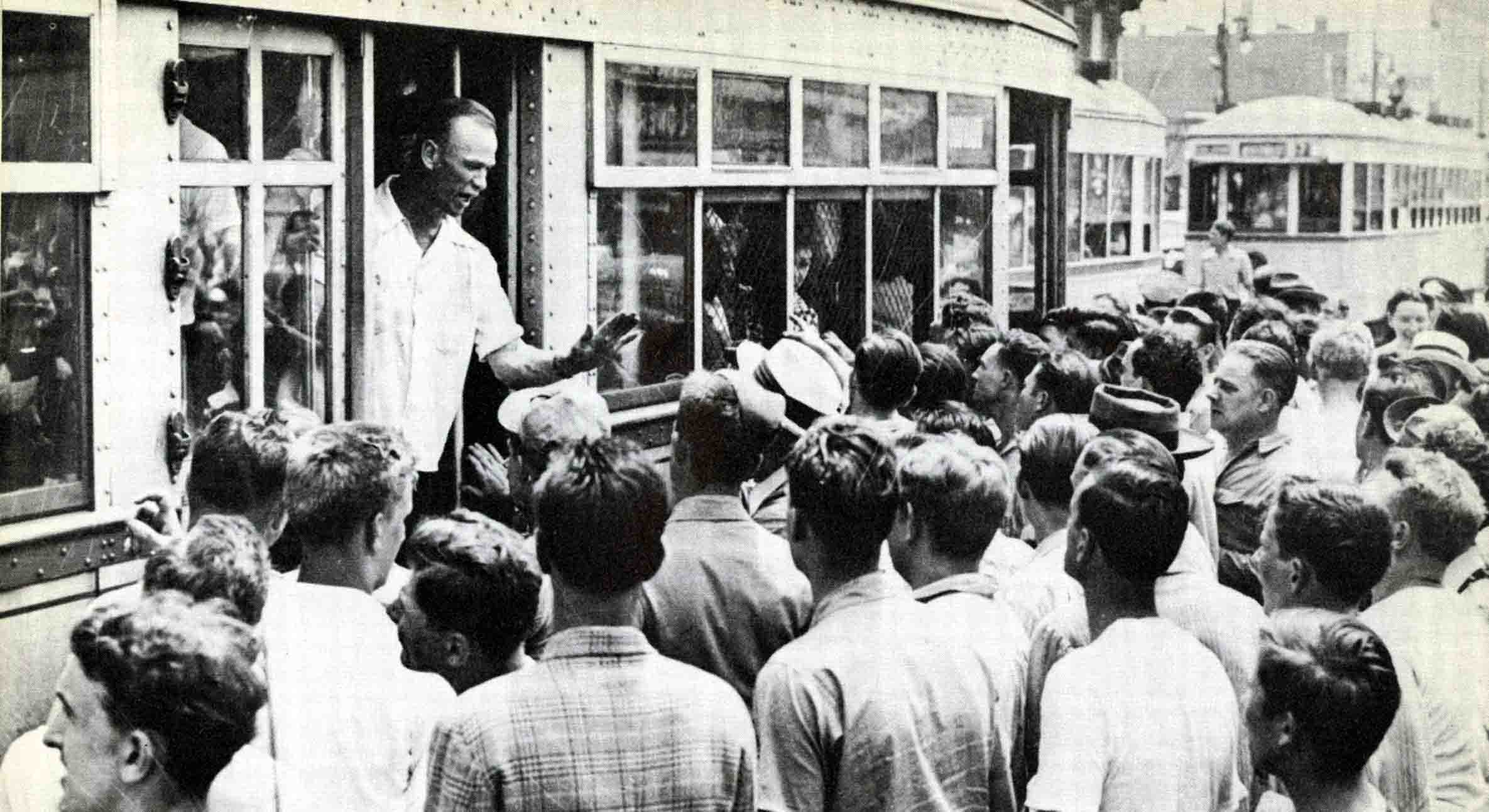

(Above, right) Yet another subtle but telling reason leading to the riot was Detroit’s antiquated transportation system, once quantitatively compared to the caliber of a small New England town. Due to severe gas rationing during WWII, many depended on the trolleys to get them to work or recreation. With the arrival of several hundred thousand Southerners into the city in the space of a few years, the trolley system became terribly overburdened. City officials believed the trolleys were carrying a staggering two million people a day. Whites who had stood in shock and revulsion at the mere thought of blacks living near them now found themselves literally elbow to elbow with them on the cramped trolleys. Many fisticuffs resulted.

Sojourner Truth - A Portent of things to come

Round One

The second “Great Migration” of Southern blacks which occurred during WWII caught Detroit badly off guard. Suddenly the city that could bury Hitler found it couldn’t adequately house its own people.

The federal government, determined to keep Detroit’s indispensable industrial juggernaut rolling, came to the realization that additional black housing was badly needed. But where would the new black housing be accepted? The sight eventually chosen was located at Nevada & Fenelon, right next to a white neighborhood.

There was only one black housing project in the city, the Brewster housing project and it was full. Southern whites were also vying for living space. Locals were under the impression the new housing project was intended for whites until it was given the name Sojourner Truth (after a Civil War slave and poet). Their protestations came swiftly. Strategies were initiated and congressmen were incited, successfully reversing Washington’s decision.

Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries was fully aware of not only the acute housing problem in his city but of the highly combustible atmosphere between the races. Siding with the blacks, Jeffries reeled off a scathing series of telegrams to Washington demanding they rescind their decision. Much to the vexation of the white community, Washington flip-flopped again and the housing project again was set for black occupancy. The move in date was to be February 27th, 1942.

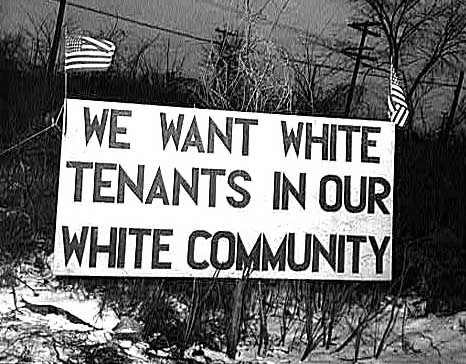

Round one went to the whites as over 1,200 well motivated protesters showed up on moving day, too much for the Detroit Police Department to control. The first black families who showed up at 9 a.m. thought the crowd too volatile and turned back. Later that day two black tenants ran their car through the picket line, starting off a melee. Detroit police used tear gas and shotguns to disperse the crowd but moving day had to be postponed indefinitely. (Above, left) Locals made their intentions eminently clear. (Above, right) Protesters pose with their “trophy.”

Round Two

April 28, 1942 – White protesters line up at the entrance to Sojourner Truth as round two prepares to get under way.

Note the protester with the over sized chunk of wood in his hand and his completely unabashed demeanor as he stands in front of the police car.

You could smell it in the air

For the generations that grew up in the era of air conditioning, relief from the ravages of the sun is only a push button away. Such extravagances were not available during WWII. The most immediate respite in those days was the public beach. If you lived in Black Bottom, this meant Belle Isle.

Sunday June 20, 1943 was a typical day downtown. The sun’s lustrous heat felt quite pleasant early in the morning but quickly spiraled to a challenging ninety-one degrees by the afternoon. Some 100,000 Detroiter's decided to patronize Belle Isle that day; 75 percent were black.

Belle Isle, the largest city-owned island park in the country, encompasses a spacious 985 acres, but it wasn’t big enough to prevent two volatile groups from avenging past grievances on this fateful day. The fury of the war had changed Detroit drastically. Because of the dense, interracial crowds that frequented Belle Isle, Detroit police came to believe that if trouble started, it would likely start here.

Ku Klux Klan - The Invisable Empire

The Black Legion

Despite the massive show of force by authorities, the white protesters showed an iron resolve. Again the two sides went at it and had to be forcefully broken up, but the black tenants were finally moved in.

With forty people injured and over one hundred arrested, sentiments still ran high. One black tenant exclaimed, “The Army is going to take me to ‘fight for democracy,’ but I would just as soon fight for democracy right here. Here we are

fighting for ourselves."

This time Mayor Jeffries was better prepared. In tandem with 1,100 Detroit police officers, Jeffries requested and was granted 1,600 National Guardsmen to secure the route and site. Round two went to the black tenants.

The inconclusive showdown that was Sojourner Truth simply escalated raw feelings between the races to a near riot status. Everyone seemed to know that somewhere in the future there would be a rematch to settle old scores once and for all. Sojourner Truth was a portent of things to come.

Problems at Packard June 5th, 1943

One step closer to judgment day - Thousands of white employees at Packard walk off the job to protest having to work with blacks.

After the U.S. entry into WWII, the federal government took over all private industries capable of producing war material. This meant for the duration of the war no more cars would be produced. The world famous Packard Motor Car Company was humming 24/7 with the vital production of the giant Rolls-Royce aircraft engines and twelve cylinder Packard marine engines used to power PT boats.

While the UAW hierarchy outwardly supported integration of its work force, its rank and file did not. Whites didn’t mind so much that blacks worked in the same plant, but they refused to work side by side with them. Three weeks before the riot, Packard promoted three blacks to work on the assembly line next to whites. The reaction was immediate and swift. A plant-wide hate strike resulted as 25,000 whites walked off the job, bringing critical war production to a screeching halt. A voice with a Southern accent barked over the loudspeaker, “I’d rather see Hitler and Hirohito win than work next to a Nigger.”

Although the matter was rectified within a few days by relocating the black workers, the wheels were quickly coming off Mayor Jeffries’ wagon. Detroit was spinning out of control and on a collision course with disaster.

Life magazine had based its article on the numerous major racial incidents in the months preceding the riot. Hot points included the Sojourner Truth housing project, Packard Motor Car Co & Eastwood Amusement Park. The Broadhead Naval Armory sat on the mainland next to the Belle Isle bridge. Fisticuffs between white sailors and black civilians had been occurring all summer long with increasing intensity.

Black youths, seeking revenge for previous incidents, had been mugging whites on the island all day. About 10:00 that night, with a traffic jam the length of the bridge, hundreds of Detroiter's were walking to the mainland. White sailors and the black youths finally caught up to each other and soon there was a racial donnybrook the length of the bridge. Detroit police came out in force, arresting dozens. Detroit police believed they had stopped the incident in its tracks but unbeknownst to them, other parts of the city, feeding on false rumors and past hatreds, began to erupt.

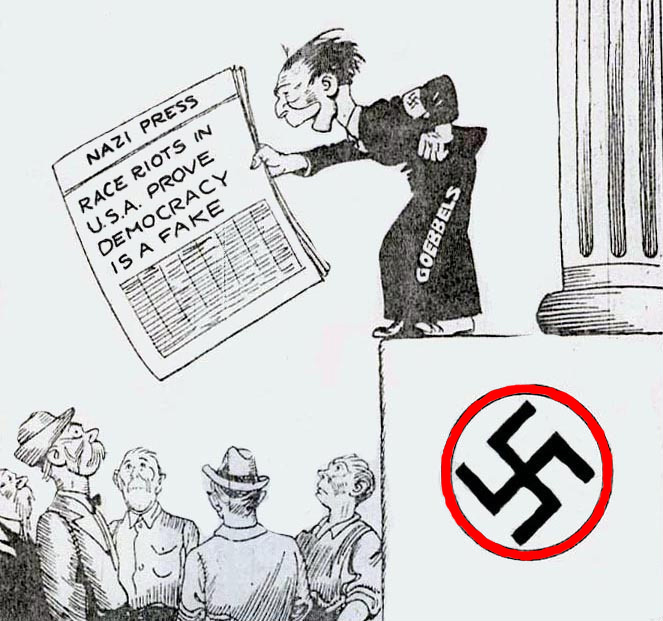

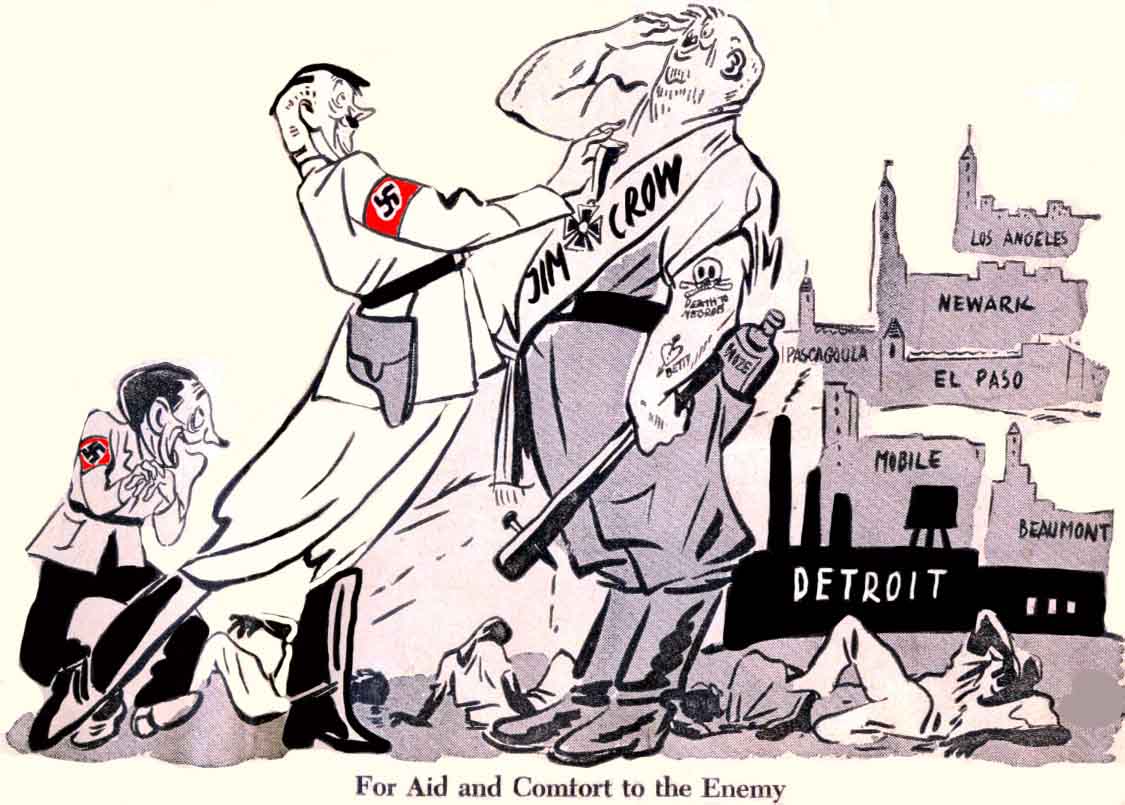

The Detroit riot of 1943, along with numerous other riots that occurred that same year, was known world wide. Nazi propaganda radio was having a field day explaining how the freedom loving Americans, who espoused that democracy was the answer, were now beating each other to death on the streets of Detroit.

An embarrassed President Roosevelt had to divert U.S. Army troops that were on their way to fight Nazis in North Africa and instead send them to Detroit to keep Americans from killing Americans.

Roosevelt found a legal loophole to keep from declaring martial law (a prerequisite for sending in federal troops) while giving the army carte blanche to apply as much force as necessary to quickly and quietly put down the riot.

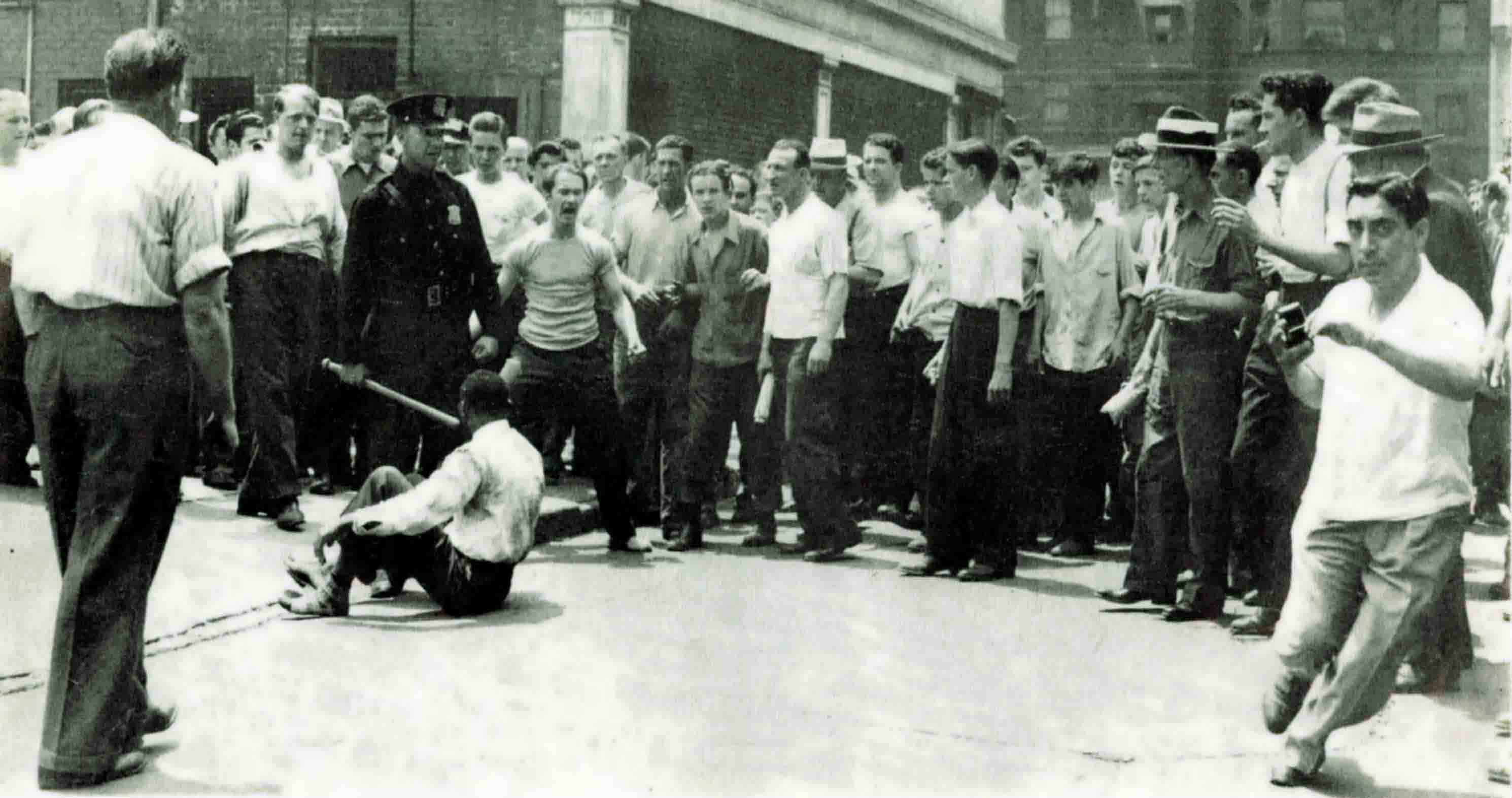

(Above & Below) Detroit police officers defend blacks from the white mob. Although the DPD was criticized for being indifferent to many of the brawls, surely these victims would have entered the long list of fatalities without them.

In every disaster there seems to emerge some sort of hero. Someone who takes great risk, not for the sake of their own personal aggrandizement but simply to quench a thirst for justice. As is often the case they remain forever anonymous.

(Above) A white passenger attempts to sway a blood-thirsty mob that was determined to assault black passengers. Note how a number of rioters closest to the car ignore his plea and continue to search the car for potential victims.

Detroit police use Tommy guns and tear gas to halt a white mob trying to enter Black Bottom in search of potential victims.

Mayor Edward Jeffries

Army Colonel August Krech, the garrison commander at Fort Custer in Battle Creek, was the senior army officer in the area. He suspected there would be trouble in Detroit and if martial law were declared it would be his responsibility to quell the disturbance.

As such, Krech conducted two mock drills earlier in the summer to see how long it would take to get troops to Detroit and he assured Mayor Jeffries he could go from the staging area at Rouge Park to the streets of Detroit in 49 minutes. Krech was good to his word but the bureaucratic bungling of his superiors who misunderstood the prerequisites of declaring martial law would prevent him from stopping the disturbance in its tracks, allowing the riot to escalate.

Edward Jeffries, mayor of Detroit from 1940 - 1948, was forced to deal with a explosive situation from the onset of his administration. Hundreds of thousands of migrants entering his city with no other purpose than to make money and thus had nothing to lose by venting their frustrations. Jeffries was livid about the Life Magazine article predicting Detroit would riot. Life is a

"yellow magazine with just enough half truths to impress anyone who doesn't know the facts."

Yet inwardly Jeffries knew the city was a powder keg. Police Commissioner Witherspoon was informing Jeffries daily of the growing number of incidents between blacks and whites, any one of which could erupt into a full scale riot. Many of the conditions, such as deplorable housing, could not be rectified in any reasonable time frame. Jeffries made a desperate plea on the radio during the riot "Our enemies could not have accomplished as much by a full-scale bombing raid. I appeal to the good citizens of Detroit to keep off the streets, keep in their homes or at their jobs."

Governor Harry Kelly

Harry Kelly was Republican governor of Michigan from 1943 - 1947. Kelly was no stranger to chaotic situations. In 1917, with the U.S. entry into WWI, Kelly quit law school to join the army.

Severely injured at Chateau-Thierry where he lost his right leg and was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

After completing law school, he began a rise through the Michigan political arena, going on to become governor and a Michigan Supreme Court judge.

Kelly, like Jeffries, was fully aware of the turbulence in Detroit. The Detroit Police Department had only 3,400 men to deal with a hostile population of nearly 2 million. Kelly and Jeffries had met with local army commanders months before the riot to discuss possible army assistance and both were led to believe that only a phone call would be needed for the army to be dispatched to Detroit. This plan was to be known as "Emergency Plan White."

Colonel August Krech

General William Guthner

Army General William Guthner was Colonel Krech's immediate superior. Guthner's superior was General Aurand. Both Guthner and Aurand were stationed at Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. When Governor Kelly's call for assistance came into Aurand's office at 11:00 a.m. Monday, his chief of staff Colonel Davis interpreted Kelly's desperate plea as a "possible" request for assistance. Thus began a number of gaffs by the army. As Aurand pondered preparatory ideas, he dispatched Guthner to Detroit to take charge. On the flight over, Guthner, like Aurand, began thumbing through the army manual pertaining to such situations.

Guthner concluded he had no authority to send in troops, only the President himself could issue such a directive. As the hours ticked by, the riot grew in intensity. Army officials in Washington, apprised of the situation, drew up a presidential proclamation allowing the army to enter Detroit without declaring martial law. At 9:25 p.m. Monday, Guthner gave Krech the green light to clear the streets.

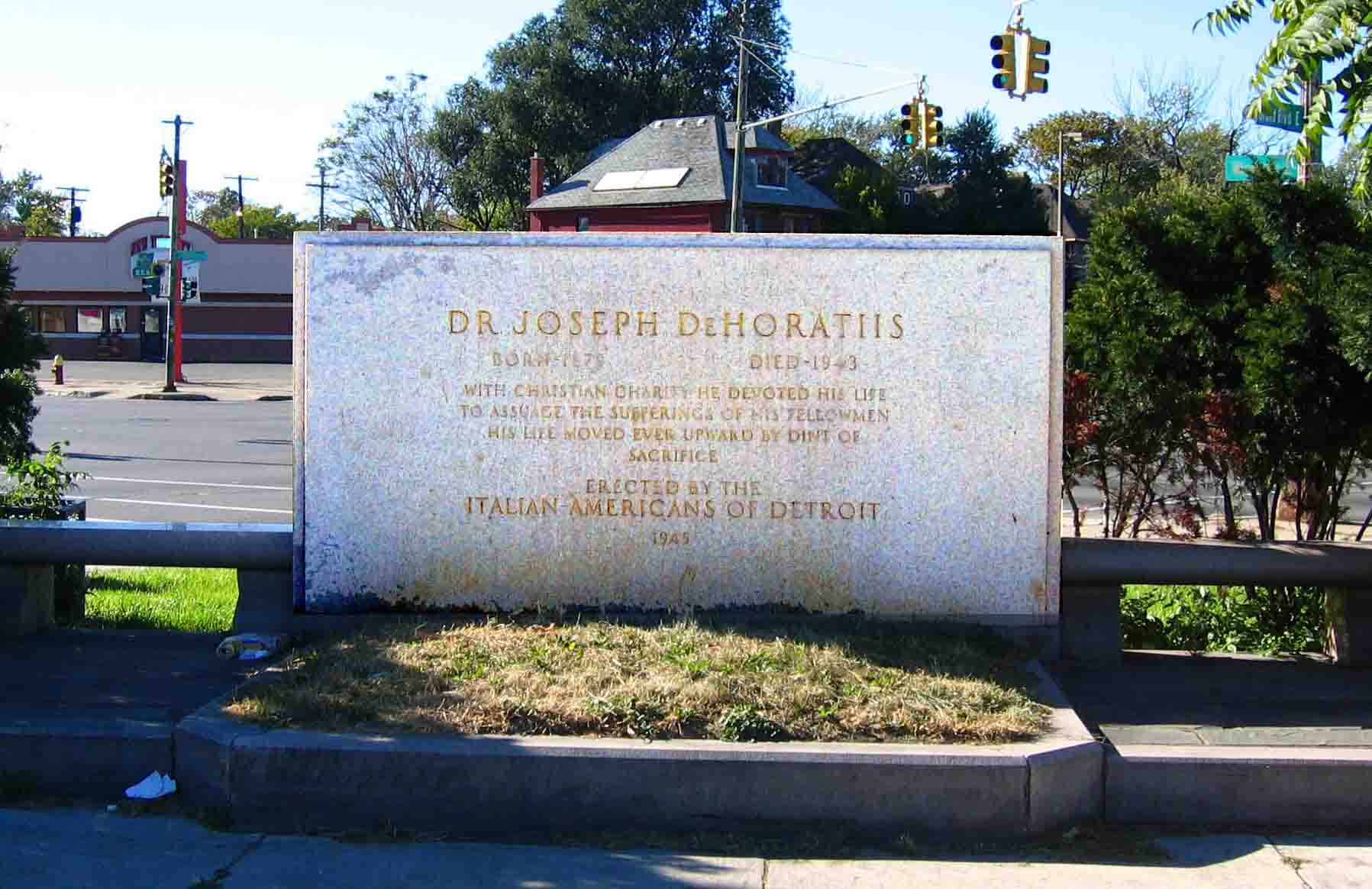

"he went about doing good"

- Acts 10:38

Dr. Joseph De Horatiis came to America with the fervent belief that all men are created equal and even the meekest of immigrants could excel. Amidst the chaos and tumult of the riot, Dr. De Horatiis received an emergency call which would take him through Paradise Valley, an all black section of Detroit. Stopped at a roadblock by a Detroit police officer, he was sternly warned about the potential ramifications. The doctor waved him off; he had a duty to perform.

By the time he got to the intersection of Warren and Beaubien he was stopped by black rioters who beat him to death.

Detroit police pull the battered and lifeless body of Dr. De Horatiis from his car which was found in Paradise Valley.

Dr. De Horatiis' stubborn but professional insistence on carrying out his Hippocratic oath would ultimately cost him his life.

At the funeral, Dr. De Horatiis’

lifelong friend, Father Hector Saulino,

brought home the gravity of the riot.

His emotion-choked eulogy ran on, reminding

us that

“Many times the good doctor refused to

take money and often paid the bills of

specialists he called into cases. Many

times he loaned great sums of money without

taking notes. After thirty-seven years of

service he died poor, owed much of that money still.

In his death Dr. De Horatiis offers a solution to all wars – Christian charity. When will the world learn that as long as men beat one another and strive greedily and selfishly against each other, peace cannot return to stay?”

Dr. De Horatiis' bier

Blessed Sacrament Cathedral

Detroit

A monument for Dr. De Horatiis off Gratiot serves as a poignant reminder of that shameful day long ago.

The Final Agony

With the riot now almost 24 hours old, white mobs attempted a final charge into the ghetto of Black Bottom. Beleaguered Detroit police, having anticipated as much, had erected barricades to prevent a certain slaughter. When shots rang out from the black occupied Frazer Hotel, the police found themselves in No-Mans land. Detroit police officer Lawrence Adams, having just answered the distress call over the radio, emerged from his police cruiser and was shot. Detroit police then unleashed a withering fire of over 1,000 rounds upon the rickety hotel, pock marking the entire face with rifle and even shot gun fire. Adams would later die of his wound, according to the Reverend Brestidge, "He was the victim of the hate of man, which has replaced the love of God in the hearts of too many of us."

Detroit police officer Lawrence Adams. Wound proves fatal.

The black occupied Frazer Hotel would host the finale of the riot.

Detroit police would storm the bastion after receiving gun fire.

Miraculously, after pumping over a thousand rounds into the structure, only one occupant was seriously hurt.

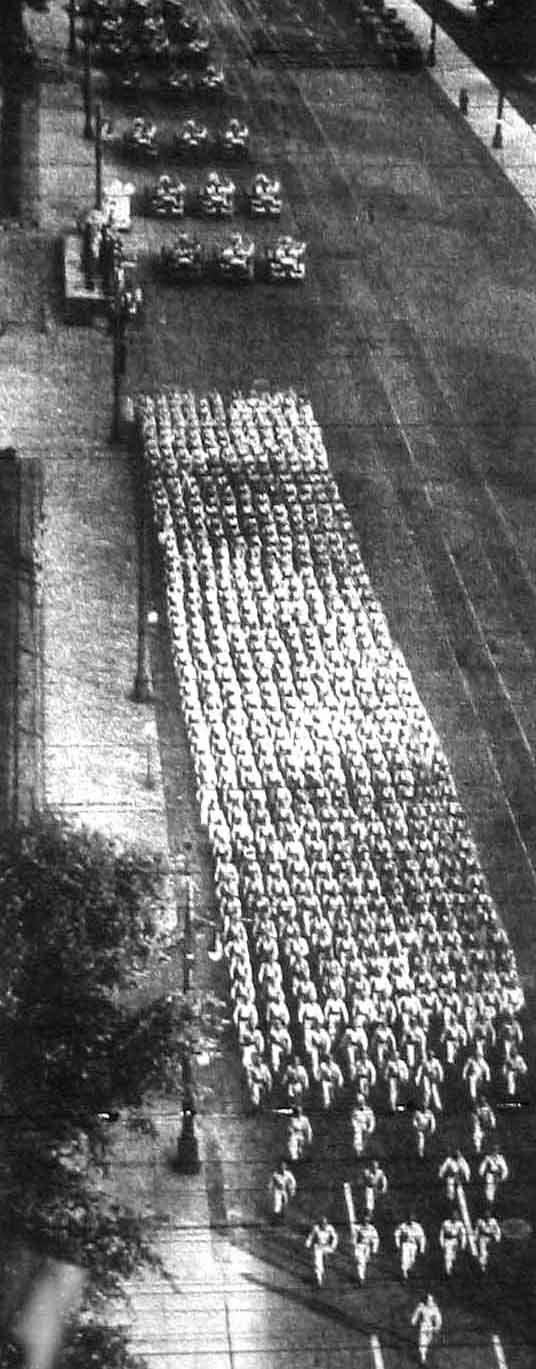

With the familiar balustrade of the Detroit Public Library (above) in the foreground, the U.S. Army heads for Woodward Avenue to break up the riotous mobs that seemed to be growing not only in size but in intensity. There they encountered between 10-15,000 whites, the "great mob" that Jeffries had seen roaming Woodward unabated and administering justice as they pleased. The sight of well armed soldiers, brandishing bayonets quickly brought them to their senses and caused them to scatter pell-mell. Krech ordered his men, "fix your bayonets, load your guns and don't take anything from anyone."

The military police then marched down Vernor Highway and into the rebellious ghetto of Paradise Valley. This proved more challenging. It was here they found the feistiest part of the white mob trying to enter the ghetto and to rumble and burn their houses down. The DPD managed to keep them at bay temporarily but were badly in need of reinforcements. The army was greeted with curses, stones and an occasional gunshot to which they answered with bayonets and tear gas. By 11:00 p.m. Bloody Monday had drawn to a deadly close. The authorities had restored order but not peace.

Mayor Jeffries post riot critique regarding the city's state of readiness had an ominous ring to it, which would echo across the decades: "We were greenhorns in this area of race riots, but we are greenhorns no longer. We are veterans now. We will not make the same mistakes again."

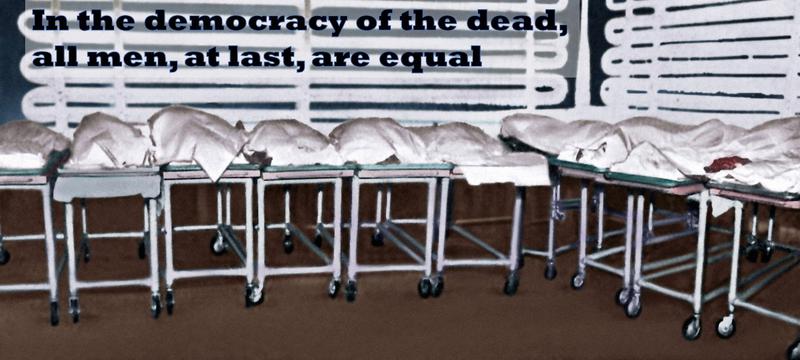

Dead - 34

Injured - 675

Arrested - 1,895

Damage - $2,000,000 ($35 million today)

Man hours lost - 1 million

Leasons Learned

Enemies in life but brothers in death, riot victims, both black and white, lay side by side in the

Wayne County morgue.

The U.S. Army, fully armed, attend a Tigers game at Briggs Stadium in the days following the riot at the behest of Mayor Jeffries. Needless to say, there were no incidents.

Of the thirty-four confirmed dead, many were killed in the most sadistic fashion possible, that of blunt force trauma. Bludgeoning's and multiple stab wound victims inundated Detroit Receiving Hospital. While killing with a gun is certainly a violent crime, it is much less personal because there is no physical contact. Of course, the greater the distance the less personal the killing. But beating a person to death with a bat or stabbing a victim thirty or forty times indicates a volcanic personal hatred of pathological proportions. This is ultimately what defined the ‘43 riot.

July 6th - With order now restored,

the army musters out of Detroit, down Woodward Avenue and past the DIA reviewing stand which held their commanders, (above, left to right) General Guthner, Governor Kelly and General Aurand.

It proved to be an uneasy peace, however, and twenty-four years later the army would return, to a city under both different and yet hauntingly familiar circumstances.

The Great Rebellion: A Socio-economic Analysis of the

1967 Detroit Riot.

As an innovator Henry stood alone amidst the world’s best.

Ford’s perfection of the assembly line would revolutionize the industry.

His five dollar day, double the industry rate, was scoffed

at by the titans of industry who viewed him as unwittingly reckless.

On the contrary, Henry Ford knew people. Unlike the entrenched

aristocracy whose riches blinded them to the true pulse of America,

Ford came up from the bottom and thus was afforded the unique

opportunity of witnessing all the layers of society along the way.

By 1915 Henry was the most famous man in the world. Henry Ford,

more than any other man, shaped the face of Detroit for generations to come.

The Old South had changed little since the Civil War. Reconstruction, despite some noble efforts by the Radical Republicans to rectify inequities, proved to be a myth. While the legal act of slavery could be eliminated, the mentality could not, especially when civic leaders chose not to enforce the law. Even well into the 1960's blacks were terrified of white reprisal if they tried to register to vote.

But it was more the everyday affronts of being treated like a second class citizen that inflicted the most egregious of injuries. By the early 1900's, Jim Crow had grown to monstrous proportions. The dehumanizing “Colored Only” and “Whites Only” signs began to appear on the scene. With each passing generation the indignities built up until a cement-like hatred permeated society. Because Reconstruction was such an abysmal failure, we would have to do it all over again in the 1950's and ‘60's.

As the post Civil War dreams of prosperity withered away for Southern blacks, one former slave lamented,

“We have very dark days here. The rebels boast that the Negroes shall not have as much liberty now as

they had under slavery. If things go on thus, our doom is sealed. God knows it is worse than slavery.”

After General Sherman’s March to the Sea was concluded, he solicited the advice of former slaves on how best to facilitate them in the postwar South. A black preacher advised him to give each free slave “40 acres and a mule.” Acting upon this, Sherman began granting ex-slaves abandoned plantation lands.

President Andrew Johnson later nullified this and ordered the lands returned to their former owners. Johnson’s version of Reconstruction was much different than Lincoln’s. Johnson saw it strictly as a reunification of North and South, not helping ex-slaves get started on a new life.

Sunday June 20

3:30 p.m. - Little Willie and co. begin marauding rampage around Belle Isle.

4:00 - Patrol car 1 begins busy day investigating reports of black teenagers starting fights.

Unable to locate suspects.

10:00 - As thousands of patrons begin to leave the island, fights erupt on the Belle Isle bridge. culminating in a

donnybrook at the foot of the bridge on the mainland side, attracting the attention of white sailors from the

adjacent naval armory who eagerly join in the fracas.

11:00 - Now some 5,000 (mostly white) at foot of bridge. Riot quickly spreads to nearby streets.

11:30 - Leo Tipton tells a black audience at the Forest Club that whites have thrown a black women and her child off the Belle Isle bridge. This was a false rumor but blacks react by smashing windows of white owned  businesses along Hastings Street,eventually looting them. Whites retaliate by beating blacks along Woodward Avenue. White mob attempts to invade Black Bottom.

businesses along Hastings Street,eventually looting them. Whites retaliate by beating blacks along Woodward Avenue. White mob attempts to invade Black Bottom.

(Bloody Monday)

12:00 a.m. Detroit police arrive en mass to break up melee on bridge. Police are unaware of Forest Club incident.

1:00 - Blacks in Paradise Valley, acting on Tipton rumor, begin assaulting white motorists along Warren and Vernor.

2:00 Belle Isle brawl is disbanded. Twenty-eight blacks and nineteen whites are arrested. Detroit police believe incident is over.

4:00 - Whites begin stoning black motorists on Woodward and assault black patrons as they leave Roxy theater.

9:00 a.m. - Mayor Jeffries and Police Commissioner Witherspoon believe riot is out of control. Governor Kelly telephones to request federal troops. Twelve hour delay before troops arrive. Thousands of whites roam

Woodward forcing blacks off street cars and buses. Rioting continues unabated throughout the day.

Woodward forcing blacks off street cars and buses. Rioting continues unabated throughout the day.

11:00 - White mobs begin reign of terror along Woodward Avenue.

4:00 p.m. - U.S. Army Brigadier General Guthner arrives from Wisconsin to meet with the mayor and governor.

Guthner balks at prearranged plan to send in federal troops. Insists that martial law must first be declared

and only President Roosevelt can do that. This would put Detroit under military rule.

6:00 - 9:00 Mayor Jeffries goes on radio appealing for sanity. Governor Kelly declares a State of Emergency,

still unwilling to declare martial law. The bloodiest stretch of the riot ensues. Sixteen are already dead

and ten more will die in these three hours.

9:25 p.m. Kelly speaks with General Aurand, Guthner's superior. A "qualified martial law" is imposed.

President Roosevelt, at his home in Hyde Park, signs the hastily prepared document. Aurand orders

Guthner to send in U.S. Army troops. Colonel Krech's M.P.'s break up mobs at bayonet point.

Detroit police complete siege of Frazer Hotel in which an officer was shot and later dies.

Riot begins to wind down.

Charles "Little Willie" Lyons

One week before the riot, Charles "Little Willie" Lyons was run out of Eastwood amusement park by a group of white teenagers. He vowed revenge.

The following Sunday Lyons showed up at Belle Isle, recruited some friends and began a marauding rampage against unsuspecting whites, successfully eluding the police. At 10:00 that night, while crossing the bridge to go home, Lyons punched an unsuspecting white man. Witnessing the event, two white sailors caught up with "Little Willie" and started a riot that would be heard around the world.

Key People