The Long Shadow of Depravity

Newark was founded in 1666 by Puritans dissidents searching for a permanent home. Unwanted anywhere else, they finally settled at a niche on the Passaic River. In 1966, Newark celebrated its 300th birthday in grand fashion. Factory whistles shrieked a salute as a parade through downtown celebrated “Pride in Newark.” Despite the fact that blacks and whites had heretofore got along in Newark, for many, the iconic motto “Pride in Newark” had a very hollow ring to it. As a plague of riots pinballed from one city to another, Mayor Addonizio announced that despite Newark’s plethora of problems “I do not believe there will be any mass violence in Newark this summer.”

Since 1900 some 100,000 blacks, refugees borne from Reconstruction, had fled the South in search of a better life and landed in Newark. Like the Puritans before them, southern blacks were dissidents from a place they were not wanted. The Puritans found peace in Newark. Southern blacks did not. One of the bitter ironies of the Great Migration was that millions of blacks left the poverty of the South for the bounty of the North just as the multitude of unskilled jobs were drying up for good. As a result the unemployment rate skyrocketed and with it the misery index of those who would become trapped in the bottomless quicksand of poverty.

The segregation blacks experienced was just as great. Newark’s poor and trampled were herded by the magic of redlining into its cloistered Central Ward where for decades their shattered dreams were allowed to fester into a spearhead of anger that was pointed right at City Hall. The enduring fact that no one appeared to be acknowledging their tragic plight and no one noticed the indignation that flowed from the Central Ward simply put a finer edge on the sword.

- Black youth, Newark 1967

The rising tide of resentment climbed steadily across America as riot after riot left a scorched path to mark the spots where frustrations had erupted into violence. The civil rights movement, despite heroic efforts to effect positive change, was not making any difference to the people who needed it the most, the impoverished and hopeless of America’s inner cities. The Stokley Carmichaels and H. Rap Browns now spoke for the ghettos.

The Crushing Sense of Nobodiness

The lumbering hulk of the abandoned Columbus homes towers above the Newark ghetto. Dreary as their appearance, the Columbus homes housed some 7,000 of Newark's poor, one of many government

housing projects that adorned the Central Ward. Children of the projects were born under a dark star.

Raised amidst extreme poverty, violence and crime, the world brands them with an indelible mark of

inferiority. It is an emotional scar that never heals.

Ghetto fathers, unable to find employment because the projects where built amidst an economic desert, find they have a cruel choice to make. Stay home and watch his kids starve or leave home so his kids can qualify for ADC and be fed. The result: an overabundance of one-parent families and broken homes with a stigma that sociologists refer to as “the crushing sense of nobodiness.”

According to sociologist Dr. William Moore, “A project home is not one in which the individual tenants really make a choice to live. Rather, it is a place to live because they have no choice. The deprived child and his family become little more than human driftwood in the urban stream of social turbulence – never fulfilling, never being fulfilled.”

Newark cabbie John Smith

Manning the front lines of Newark’s rebellion was a large contingent of Central Ward teenagers.

Having known only poverty and deprivation their entire, miserable lives, it took little coaxing from adults

to prod them into action.

Dr. Wyman Garrett, a prominent black doctor who hailed from Newark and fought his way out of the slums, never forgot the old adage about remembering where you come from. During the Newark Riot, Dr. Garrett traversed the treacherousness streets attempting to persuade the teenage rioters to return home. He later observed, “The veneer that used to cover up the hate is slipping. They’re used to being rejected by the establishment of having committees formed to solve problems that don’t have anyone on them that they know and trust. You know what really got me during the riot, when I was out trying to get them off the streets. Here were these fifteen-year old kids; I didn’t see any fear in their eyes, not a bit of it. The cops and

Guardsmen were scared, and I was scared. But not those kids. They said to me, ’Doc, you got some reason to live, you’re somebody. You go on home. We don’t want you to get hurt.’”

Post Riot - An Unending Nightmare

Richard J. Hughes

New Jersey Governor

New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes tried to rationalize the devastation.

“They (blacks) are not oppressed by government. They are oppressed by circumstances. There exists behind them one hundred years of discrimination and cruelty to them, in spite of the efforts of many sincere men to eradicate the cruelty and to bring a day when oppression will no longer be with us.

When one considers that, no matter what any administration – city, state or national can do, the roots of poverty and discrimination that have developed over a century can’t be eradicated in a short time, even with all the good will in the world.”

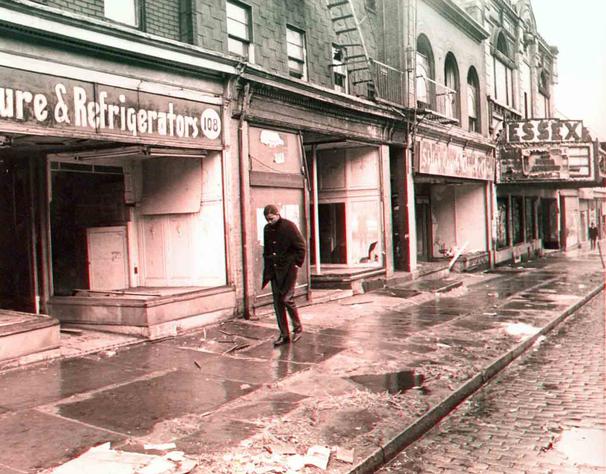

Above: A man walks the post-riot devastation of a ghostly Springfield Avenue with the full knowledge that things will never be the same again.

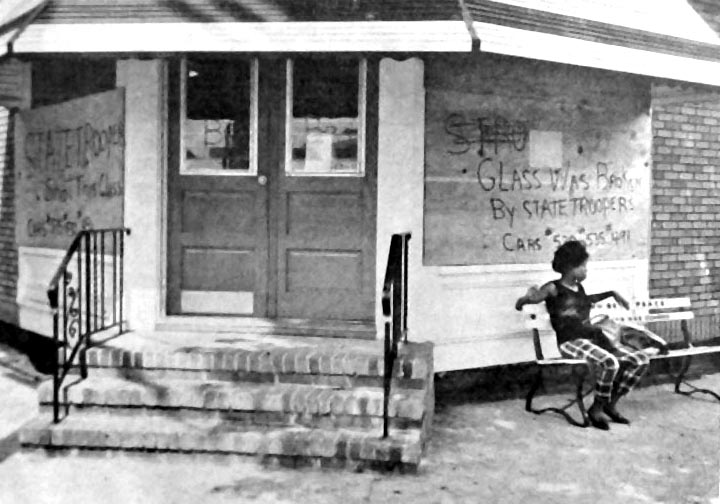

Below: Shop keeper vents her frustration by fingering State Trooper cars # 530, 535 & 491 as the ones who shot her store up.

Public Housing - High Rise Hell

High-rise public housing was the federal governments answer to the critical post-war housing shortage that overwhelmed many of the big northern cities. It would prove to be a failure of catastrophic proportions. It was a thinly veiled attempt to house as many impoverished people as cheaply as possible on the smallest parcels of land by stacking them one on top of another. Since these projects were built over the ruins of old slums, tenants often found themselves in an economic no man’s land, setting the stage for high unemployment, crime and a permanent underclass on a mammoth scale.

To circumvent over inflated land prices and meet the stingy federal cost regulations, designers had no other recourse but to build straight up, often twelve to eighteen stories. The dreary, monolithic appearance was also intentional to remind its inhabitants that they were indeed underclass. Sociologists were aghast at this new governmental strain of logic. They had prophesized about the perils involved with a beehive-like concentration of poverty-stricken people under one massive, hastily designed roof. But the projects were cranked out in cookie cutter fashion. In some cities, as many as 33 eleven story buildings were haphazardly jammed together. Detached from the rest of society in their own cultural vacuum, failure was almost assured.

Ass Deep in Corruption

Newark Mayor Hugh Addonizio was no stranger to flying bullets. As an army officer during WWII, he had stormed Omaha Beach as lead filled the air and survived the renowned Battle of the Bulge, earning himself numerous meritorious

accommodations. In July of 1967 Addonizio would witness another battle of prolific proportions, on the very streets of the city he was charged with protecting.

But Addonizio was an embattled mayor long before revolt came calling. A seven term U.S. congressman, he was elected Newark’s mayor in 1962 claiming he wanted to help his native city. There was a darker side to Hugh Addonizio, however. To a confidant he is alleged to have said, “There’s no money in being a congressman but you can make a million bucks as mayor of Newark.”

These sentiments were buttressed by the fact that in 1970, after eight years as mayor of Newark, he was sentenced in a U.S. court to ten years in prison for extortion. According to the U.S. attorney who prosecuted Addonizio, he was guilty of “literally delivering the city into the hands of organized crime.”

His critics claimed during his tenure that he sold everything except the City Hall building itself.

Embattled Newark Mayor

Hugh Adonnizio

It was under this felonious atmosphere that Newark began its tragic decent towards rebellion. Addonizio inserted a close associate, Dominic Spina, as head of the police department. Under his direction few officers got ahead on merit and the NPD quickly earned a reputation for being as corrupt as the crooks it was supposed to be subduing.

Blacks had become the majority in Newark but held only a few token positions in city government, a transparent attempt by the mayor to exhibit solidarity. Addonizio’s tenure had become too controversial – too many police incidents, unarmed blacks being killed, police guns mysteriously discharging, police brutality and City Hall corruption.

As 1966 turned into 1967, the final pieces of the rebellious puzzle would be put into place. The state of New Jersey was looking for a city to build its State College of Medicine and Dentistry. Newark leaped at the challenge, offering fifty acres from the black, Central Ward which was already undergoing an extensive urban renewal program.

The school’s board of trustees recoiled in horror at the thought of building in Newark. Their hidden agenda was to build out in the spacious and tranquil suburbs. The political logrolling now began in earnest.

Addonizio was determined to land the medical school and use it as a springboard for his gubernatorial ambitions. Attempting to checkmate the issue once and for all, the school board insisted they must have 150 acres to build on. Anticipating this, Newark countered with a 185 acre bid, much to the dismay of the school board. In one last desperate ploy to keep out of Newark, the school board pointed out that the first fifty acres they wanted were not of the land already cleared for urban renewal but land across from the renewal area that had not been cleared, nor was it scheduled to be.

The black community, whose dwellings were to be razed, were livid. If it was their houses that were to be sacrificed then they wanted them replaced with more housing. It seemed like another case of “slum removal = black removal” and under the guise of eminent domain they were powerless to stop it.

With this atmosphere of anger hovering over Newark, the last piece of the puzzle fell neatly into place in June of 1967. The secretary to the board of education, Arnold Hess, was preparing to resign. The black community petitioned for Budget Director Willie Parker, a black CPA, to be appointed to the job. Since Newark public schools were predominantly black, it seemed like a logical fit. Instead, Addonizio made a decision that came to mystify many. He appointed a white crony of his, who possessed only a high school education, to be the new board of education secretary.

Sparks flew until 4:00 a.m. at the next board of education meeting to such a heated degree that a black community leader threatened, “Newark might become another Watts.” Unwilling to cave, Addonizio instead convinced Hess to stay on for another year, which in effect pleased no one. City officials blundered on in ignorant bliss on these issues, still believing the black demonstrations to be nothing more than a speed bump along the road of progress. The outrage should have been a warning sign. This was not the same passive Newark from years gone by. Typical of the newfound attitude among black teenagers was this quip from a sixteen-year-old Central Warder:

"Picketing and marching ain’t getting us anywhere man.

Despite the spin from city hall, things were not well in pre riot Newark.

Sticks and Stones

July 12th, 1967 was a steamy Wednesday in Newark. Around dusk that evening cab #45 double-timed it towards the intersection of 7th and 15th Street. Piloting it was John Smith, black, forty years old, an army veteran and trumpet player. As he approached the intersection he noticed a Newark police cruiser with two white officers inside seemingly double parked. Smith, who had a checkered driving record to say the least, flipped his lights and passed. The police cruiser followed and pulled him over claiming they were moving and he was tailgating.

From here on none of the stories jive but what is known is that Smith was arrested by force (allegedly resisting arrest) and was taken into custody. Upon their arrival at the 4th Precinct, Smith’s beaten body was dragged into the station (according to police he refused to walk on his own. According to Smith he couldn't walk) as hundreds of roving eyes glared out the windows of the twelve story Hayes public housing towers across the street. This momentary lapse of discretion would cost the police dearly.

A volatile crowd from the Hayes complex began to accumulate outside the 4th Precinct. Their lifelong contempt for police was accelerated by the terrible tensions that had reached a crescendo in the previous months. Rumors began to circulate that Smith had died in police custody. Community leaders demanded to see Smith. They found him in his cell doubled over and groaning, his ribs stove in and cuts on his face. Realizing they had been “caught,” the police started passing out riot helmets.

A ring of white and black police surrounded the station. Angry blacks from the Hayes Homes were giving them the business but, despite their unbridled hatred of the white police, saved their choicest comments for the black officers. “You Uncle Toms got to come home tonight.” Smith was taken out the back exit to the hospital while leaders tried to calm the restless crowd still accumulating out front. It was too late. Shortly before midnight a well placed Molotov hit the side of the station house followed in short order by bricks and bottles, breaking almost every window. Club wielding police charged out the door to put down the insurrection. The battle for Newark was on.

Looting quickly broke out within sight of the 4th Precinct. One local leader who witnessed the initial looting was critical of the sluggish police response. “The radio cars were going back and forth and they saw them in there. They saw them in there getting whiskey and they just kept going. They didn’t try to stop. As a result of that, all the people saw that the cops didn’t care, so they went in too. A lot of stuff could have been avoided at this point.”

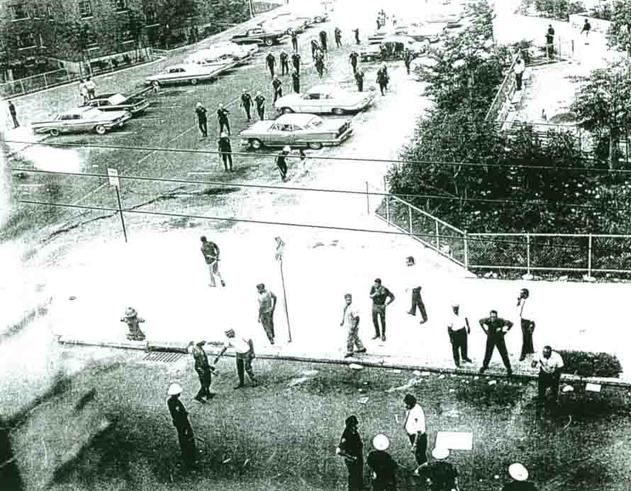

Newark's 4th Precinct found itself in the precarious position of being surrounded by public housing projects whose thousands of occupants they were not in complete sympathy with. The 12 story Hayes complex in particular offered a commanding view of the 4th precinct. During the riot, snipers atop the Hayes complex would fight pitched duels with officers 100 yards below.

By Thursday afternoon, with a relative calm restored, police Director Spina naively believed the riot was over. By 7:30 that evening the riot started anew, again in front of the Hayes housing projects. By 9:00 the Central Ward was in total rebellion.

Protestors from the Scudder housing projects vent their considerable anger at

police, unaware that the odds are about to change.

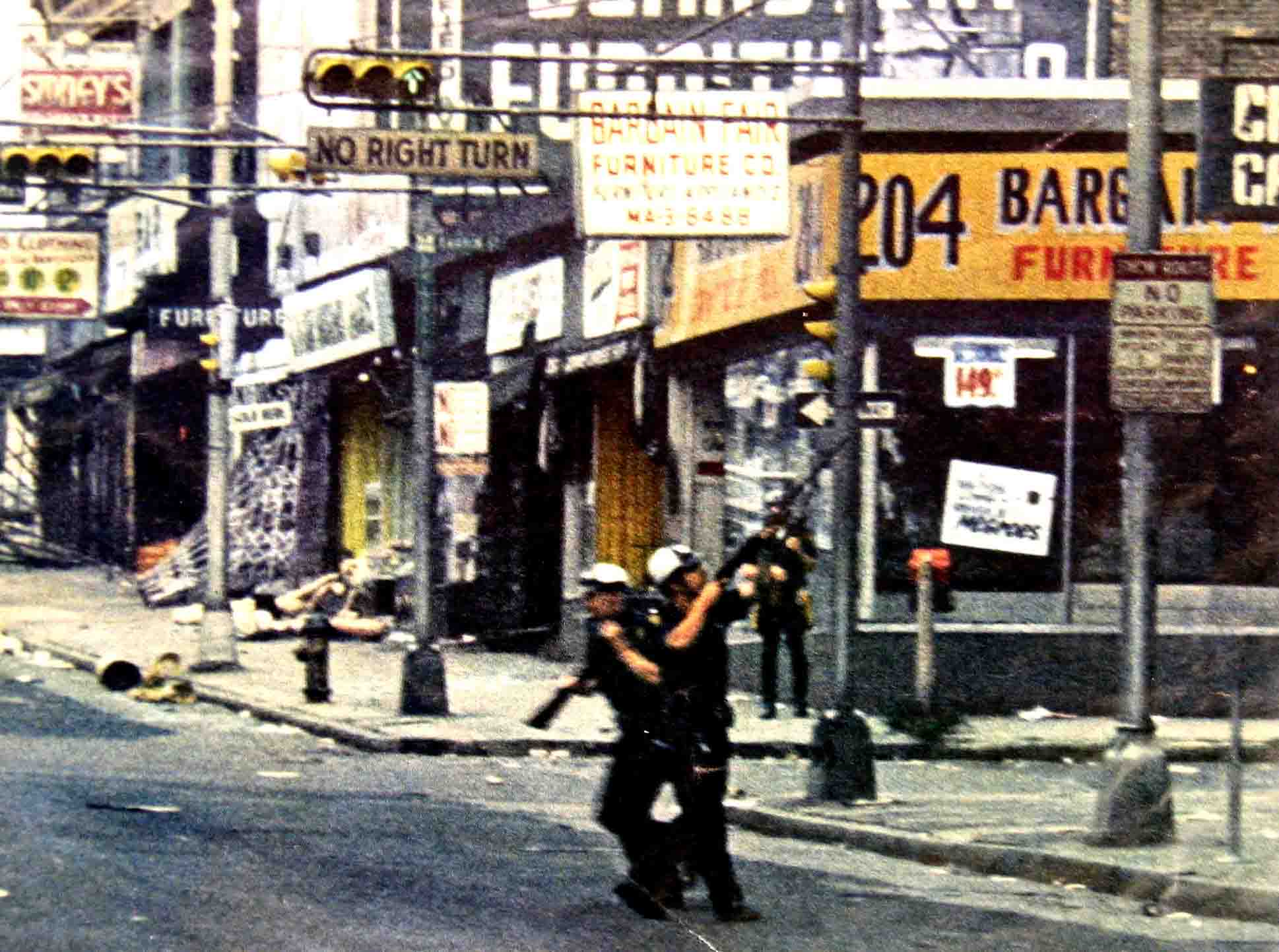

Despite the plethora of ominous warnings throughout the long, hot summer, Newark police seemed poorly prepared for trouble. The New Jersey State Police, which was on standby since the alert sounded on Wednesday, were baffled, as this note in their log book suggests:

There is still no organization within the Newark Police Department.

"Like Laughing at a Funeral"

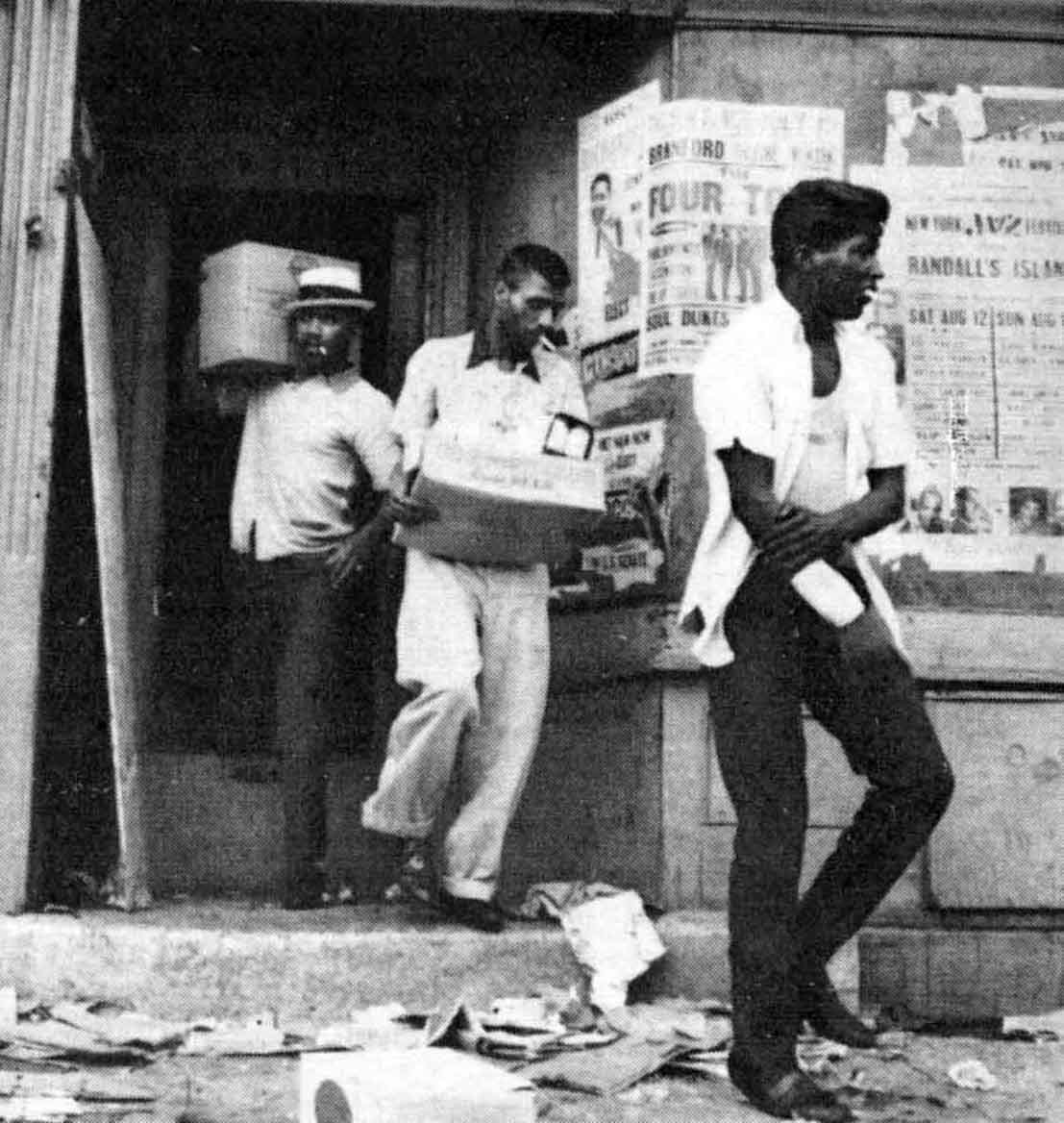

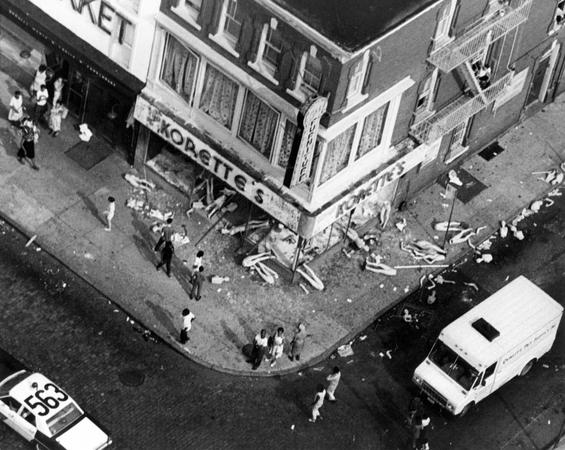

When the looting was not challenged immediately it snowballed to avalanche proportions. Denuded mannequins bare mute testament to the wholesale thievery.

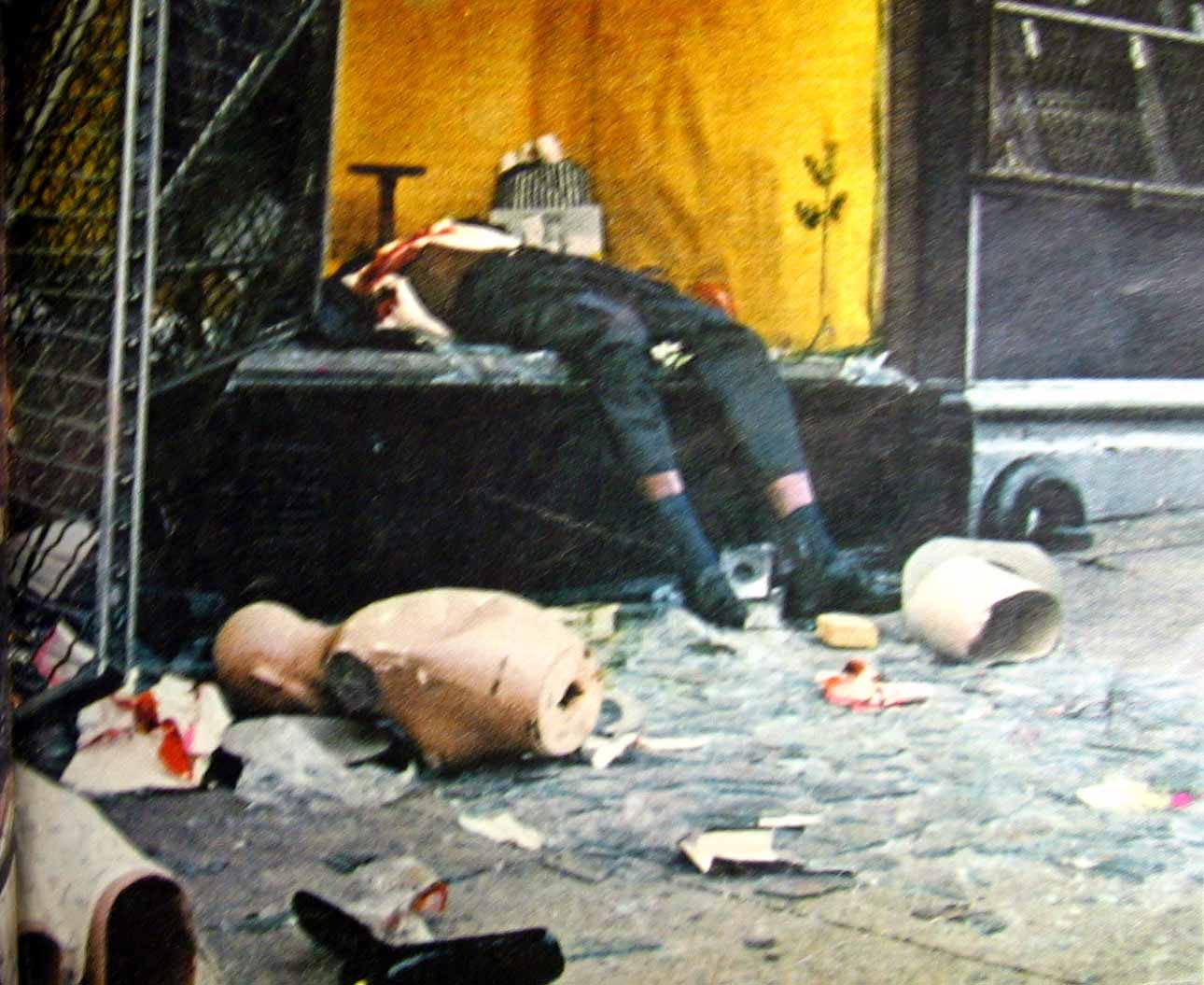

As the riot slid out of control, the authorities stepped up their enforcement. The looter on the right was shot to death moments after this photo was taken.

At 2:20 a.m. Friday, Mayor Addonizio, who had been in a state of confusion and lethargy from the onset, finally called Governor Hughes to request the State Police and National Guard. When Colonel Kelly of the State Police arrived at City Hall an hour later, he found Addonizio in a virtual state of shock. “It’s all gone, the whole town is gone,” Addonizio moaned. “It is all over.”

Springfield Avenue, the old Jewish thoroughfare which ran through the Central Ward of old Newark, bore the brunt of the rioters retaliation. As the looting commenced the projects spilled out onto Springfield Avenue and systematically ripped it apart in both directions.

Early Friday morning Governor Hughes and Mayor Addonizio toured the devastated Central Ward in person. As their state police led motorcade meandered through the carnage, the despondent duo recoiled at the looting still in progress.

One couple in their new car stopped at a looted shoe store and skillfully packed their trunk as if it were a picnic basket. The looters paid little heed to the latent authorities, carefully plying their trade and coolly making off with their ill-gotten swag. Hughes particularly was aghast at the looting in broad daylight and the carnival like ambience which hung in the air. “The thing that repels me is the apparent holiday atmosphere I saw with my own eyes. It’s like laughing at a funeral. And it could be the funeral of the city.”

The riot flared to a fiery apex on Friday afternoon when Newark police were summoned to the Scudder housing project to investigate a reported sniper. What happened next depends on who tells the story. It is believed that several blacks from the project had been shot an hour earlier by the Newark police. Unaware of the hornet’s nest they had entered, the police were beginning their investigation when a puff of smoke jutted out from an upper floor window of the Scudder towers. Newark police detective Frederick Toto, standing amongst his comrades, was felled by a bullet to the chest. He died on the operating table two hours later. It was after the death of Detective Toto that all semblance of restraint on either side was lost for good. From now on it would be an eye for an eye.

After the death of Newark police detective Frederick Toto from a sniper at the Scudder housing projects, all hell broke loose. Guardsmen retaliated by opening up with their machine guns on any and all stores that had "soul brother" or "Black owned" hand written on the windows.

At Left, this looter, perhaps after a stylish hat or fancy shoes, paid for his foolishness with his life.

Children of the poor were born under a dark star. Raised amidst an island of poverty, violence and crime, the world brands them with an indelibe mark of inferiority. it is a emotional scar that will never heal. According to sociologist Dr. William Moore, "A project home is not one in which the individual tenants really make a choice to live. Rather, it is a place to live because they have no other choice. The deprived child and his family become little more than human driftwood in the urban stream of social turbulence - never fulfilling, never being fulfilled."

Built: 1959 Demolished: 1987

165 Court Street

The Scudder housing project was named after Edward W. Scudder whose claim to fame was being publisher of the Newark News which was founded by his father.

Newark’s tragic triangle - Decades of disgust and resentment finally give way to demolition as the Scudder Homes are reduced to dust in 1987. Off in the distance, Stella Wright (back, right) and the hulking mass of the Hayes project (far left) await their turn at oblivion. It was the fitting end to the nightmare of high-rise public housing.

Scudder Homes prepped for long overdue demolition

Newark - The Anti-Climax