| ||||||

President Lyndon Johnson, like his predecessors Eisenhower and Truman, echoed the need for rebuilding our big cities, “Our society will never be great until our cities are great. In the next forty years, we must rebuild the entire urban U.S.” Urban renewal, the much vaunted plan for erasing blighted neighborhoods while hiding behind the cloak of helping the poor, in many respects hurt the poor and destroyed once vibrant (albeit decaying) neighborhoods, and replaced them with class-conscious pipe dreams that were socially incongruent to their surroundings.

Urban renewal was the rage across the country in the 1950s but it was virgin territory for city planners. It had never been done on such a colossal scale before. New York City razed large sections of viable neighborhoods, including the venerable Penn Station in 1963, and spent the rest of the twentieth century wondering why. It was the old American adage rearing its ugly head once again: 'bigger is better.' The more money you throw at a problem the greater your chances for success. Right? Wrong!

On paper urban renewal seemed like a very progressive endeavor - erasing blighted areas and replacing them with modern dwellings brandishing cutting-edge innovations. Below the surface, however, the iceberg of urban renewal reeked of political snake oil. Urban renewal was not used to help the poor. It was used by big cities to fatten their coffers. It was also a last ditch effort to halt the every accelerating white flight to the suburbs.

By razing impoverished slums and replacing them with middle-class high rises, a city’s tax revenues would swell significantly. Officials stumbled ignorantly on with their social engineering as entire neighborhoods were leveled under the guise of modernity. The melting-pot poor who were hastily sent packing had to fend for themselves with little or no relocation help from the city. Since it was generally poor blacks who were being displaced, many came to believe the city’s hidden agenda of slum removal was really black removal. While the cosmetic appeal of erasing Detroit’s most blighted areas would be obvious, city planners failed to take into account the terrible social upheaval they were causing.

Between the three mayors involved in urban renewal in Detroit (Cobo, Miriani, Cavanagh) they would level thousands of acres of old neighborhoods and in the process create an angry army of displaced blacks who, in the volatile decade of the 1960s, would ultimately unleash their considerable fury against the city itself.

Urban Renewal

one step forward...

...two steps back

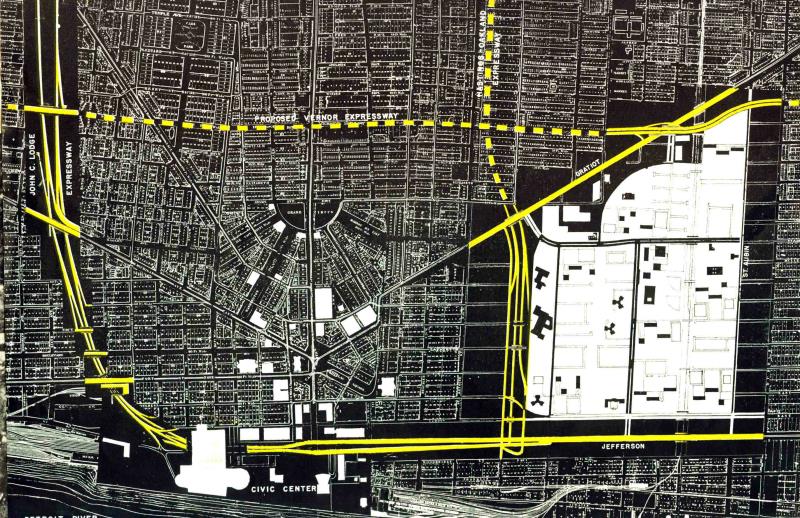

Original urban renewal map showing the highlighted Black Bottom area bounded by Jefferson Ave, St. Aubin, Gratiot and what was initially called the Hastings/Oakland expressway. Now called I-375, this was the famous Hastings Street of John Lee Hooker fame from the 1940s.

The condemnation of property in Black Bottom began in 1950 and continued for three years. This initial development contained seventy-two acres, fifty-five of which would be residential development and seventeen would be set aside for a park. With great anticipation the city conducted a lottery for the cleared land in July of ‘52 to determine who the lucky builders would be to transform this former slum into an urban utopia. It was then that something unexpected happened. Much to the city’s consternation, no one bid on the land. The silence at city hall was deafening. An embarrassed Mayor Cobo named a twelve man committee to fabricate solutions. His vision remained undimmed.

Above: The completely razed Black Bottom district looking inwards towards the city in 1955.

Black Bottom was now only an urban desert. It would lay dormant for six years because no developers showed any interest.

Below: The newly plowed up acreage was slowly retaken by nature, causing critics to sardonically refer to it as “Ragweed Acres”.

Detroit Mayor Louis Miriani (holding shovel) was forced to pick up the pieces after Mayor Cobo died of a heart attack in 1957. Above, Miriani is taking the first ceremonial shovel of earth for one of the Gratiot projects in 1958.

The first building to go up in 'Ragweed acres" was the Pavillion, a large, middle class apartment complex in the heart of the former Black Bottom. Designed for the middle class, white or black, the Pavillion was an attempt to keep the middle class, and their tax dollars, from fleeing to the suburbs.

While developments like the Pavillion did have some marginal success, by the 1960s people wanted

the wide open spaces, the 'grass and garage' environment that only the suburbs could provide and the newly installed interstate highway system was the vehicle that would get them there.

Out of the litany of reasons given by local governments justifying the terrible disruption caused by urban renewal projects, two stand out. Old, dilapidated dwellings are indeed an eye sore and create conditions contrary to positive, progressive movement. Also, as noted in the chart above, is that poor people pay little or no taxes. The city believed that by removing them and their dwellings and replacing them with middle class, the city would not only benefit substantially from additional revenue but would halt white flight and maybe even lure people back to the city.

Ode to Corktown

Every time I hear it

The Detroit Plan - A Genesis

As Detroit entered the turbulent 1940's and WWII, her industrial might made it world famous but it's residential housing, embarrassingly enough, was approaching 3rd world status. Something had to be done. Enter Mayor Edward Jeffries and the Detroit Plan.

The Detroit Plan of 1946 included massive slum clearance on an unprecedented scale and super highways to alleviate and accelerate traffic. The completion of such a grandiose scheme, it was reasoned, would propel Detroit into elite status and save the career of Mayor Jeffries who was still smarting from the fallout over the 1943 riot. There was one formidable obstacle. No city in the country had the capital to complete such an immense undertaking. This project would require Herculean muscle. Enter President Harry Truman.

Edward Jeffries

Detroit Mayor

1940-1948

Harry Truman

President Harry Truman's 'Fair Deal' sought sweeping changes to improve the country's crumbling infrastructure. He implored congress to greatly increase the number of suitable dwellings for low income Americans. His wrangling paid off in the form of the landmark Housing Act of 1949 which called for "a decent home and suitable living environment for all Americans." For the first time in history, mountainous amounts of money were made available to cities to help them wipe out slums and plant the seeds of modern housing.

The Detroit mayoral election of 1949 took on historic proportions. After the Sojourner Truth uprising of 1942 and the vicious race riot of 1943, Detroit was a boiler with defective pressure relief valves that was once again about to explode. Hundreds of thousands of Southerners, black and white, had entered the city during the war looking for work. Most of them stayed after the war. Detroit was always woefully behind in its ability to house it's people. Now the housing shortage was approaching catastrophic proportions.

The main issue surrounding the election of 1949 were twelve proposed housing projects, eight of which would be black housing projects placed in white neighborhoods. Republican candidate Albert Cobo was unabashed when he stated that if elected he would veto all these projects. His Democratic opponent, George Edwards, stated he would approve them. Edwards had been a UAW officer with strong labor ties in a very blue collar town yet he was trounced in the racially charged election and Cobo went on to solve the burgeoning housing problem his own way, via urban renewal. As Mayor Cobo took the reins of the city, Detroit stood at the precipice of history.

George Edwards

Albert Cobo

The 1943 race riot in Detroit greased the skids for white flight to the suburbs. Detriot had already lost over 150,000 people with no sign of a let up.

Cobo aimed to stop this by re-inventing city living, or using the moniker of the day, creating 'a suburb in a city.'

Urban renewal created tremendous upheaval that would permanently attached itself to Cobo's legacy.

Edwards worked for the Detroit Housing Commission in the early 1940s and witnessed the 1943 race riot and the Sojourner Truth uprising. He was appalled at the plight of blacks in Detroit but felt helpless. Seeing an opportunity, he ran for mayor on a progressive platform determined to help blacks improve their lot.

The Frankenstein monster of Urban Renewal

On a national basis, slum areas were producing 6% of big city revenues while consuming 45% for urban services. Detroit's Gratiot area had never, even when new, been characterized as a fine residential neighborhood. Initially populated principally by German immigrants in the 1850’s, the community had become occupied almost entirely by blacks flocking up to Detroit factories from the South. About half of its small frame houses were more than fifty years old by 1946. More than 90% were absentee-owned. According to the 1950 census of Housing, some 1,050 dwellings, about 2 out of every 3 were substandard. These were in various states of dilapidation, with no running water, no private bath, outhouses, and the absence of virtually every basic convenience necessary to health, comfort and safety.

Physical deterioration brought its inevitable social consequences. Here the crime rate was higher than anywhere in the city; fires were more frequent in occurrence and more disastrous in casualties. Rat bites brought daily victims, usually among children, to the nearby Receiving Hospital. Death rates from Tuberculosis, infant mortality, accidental deaths, infectious, parasitic, venereal and other diseases were substantially higher than the city of Detroit as a whole.

Many cities are searching for solutions to the same problem. Some try to cover their municipal corrosion with a layer of the old political snake oil. Some blast, then rebuild new slums. In Detroit, where the problem was born, a group of prominent citizens think they have a significant new solution: under Title One Redeployment, they say build mixed suburbs inside the city, mixed both in building types – high rise and low – and in population, a mingling of races. In general the economic distribution will locate the highest priced housing in the center, the next highest on the periphery and the low cost in between.

Black Bottom prior to demolition.

The new plan for Gratiot uses the new interstate highways as the founders of Detroit use the river, to give suburbanites the tool to come back to the city. Unfortunately, the interstates actually increased the white flight. In 1950, the region which had been designated part of the Gratiot Area Redevelopment project was 95.7% “non-white” according to government statistics. Many were given only weeks to find new housing in a city with little housing to spare. The federal Housing Act of 1949 did not require local governments to facilitate the relocation of single people.

All in all, 20% of the city's housing stock was scheduled to be torn down.

The Gratiot and the neighboring Lafayette redevelopment sites were merged to create Lafayette Park. Detroit’s urban renewal program (as of 1967) included 41 projects – 28 for redevelopment and 13 for conservation. These projects cover about 11,000 acres or 12 percent of the city. Of the 41 projects, 27 are federally assisted and 14 are financed entirely with city funds. Total cost of the federally assisted projects is estimated at more than $200 million (in 1967 dollars, prorated to $1.52 billion in today’s dollars). The federal government’s share is $130 million ($988 million) and the city’s share is $70 million (532 million). Generally, two-thirds of urban renewal is paid for by the federal government, using money appropriated by Congress.

Violence, although intolerable, has its roots in grievances that are also intolerable. If any man should deny this, let him also say he would be willing to have his child assume a black skin and grow to manhood in a black ghetto.

Mayor Albert Cobo, (pointing) directing traffic in the newly cleared Black Bottom area.

"Sure, there have been some inconveniences in building our expressways and slum clearance programs, but in the long run more people benefit. That's the price of progress."

Cobo's urban renewal plan was unpopular in some circles but the fact remains that he presided over a city with an ever shrinking tax base. The well-to-do were disappearing to the fledgling suburbs and being replaced by poor who paid little if any taxes and were a drain on city resources. Urban renewal was a last ditch effort to save the city which put the world on wheels.

No one ever doubted that Black Bottom required attention. These wood framed houses were originally built for the influx of German immigrants who arrived in the 1850s. Hastily fabricated, they were way past their life expectancy by 1950. Few had running water or bathrooms. The cruder forms of outhouses were simply a seat placed over the sewer. The threat of a major fire was always present. The frequency of rats also made the area unsafe. Despite its cultural history, the blight of Black Bottom had become an embarrassment to city officials who were attempting to re-invent Detroit.

The Death of Cobo

Detroit Mayor Albert Cobo returned home on Sept 12, 1957 and was felled by a massive heart attack. He was rushed to Henry Ford Hospital where doctors say he rallied several times but eventually slipped into a coma and never came out.

Cobo was the prime mover of the massive effort to revitalize a decaying city. His urban renewal projects left huge scars in the city's topography and it would be up to his successor, Common Council President Louis Miriani to drag this undertaking across the finish line.

Though regarded as a good mayor by 1950's standards, Cobo definitely set in motion a social minefield of problems which would later explode on his successors. Perhaps history had granted him leniency because he died in office. Nevertheless, his failure to address the acute housing shortage may have pleased his constituents, but it was to spell doom for the city in the racial upheaval of the 1960's.

Vs.

Mayor Albert Cobo lying in state

Eatless Days in Black Bottom

Just as Ellis Island was a point of entry into the U.S. for European immigrants, Detroit's Black Bottom was a point of entry for Southern blacks who had migrated looking for a better life.

In some respects they found that. Finding employment in the auto factories, blacks could make more money in one day than in a month as a sharecropper. But the hazards were still there. Instead of dodging rattlesnakes in the cotton fields they were dodging molten metal, sparks and pollution of the foundry.

Because of racially restrictive covenants, blacks weren't allowed to buy houses and found themselves renting dilapidated housing in the Black Bottom district. Absentee landlords, fully aware of the housing shortage, charged blacks double and triple, causing multiple family's to squeeze into a single dwelling. When economic depression came, blacks were the first to get laid off. It was sleepless nights and eatless days in Black Bottom.

The most legendary athlete to emerge from Black Bottom, one that epitomized the community by never giving up, was heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis.

Louis, who was born in Alabama, enjoyed recounting his long journey which centered on Detroit: "I was twelve years old when Pat Brooks (step brother) heard about the money Ford was paying. He went up first and then brought us up to Detroit. We moved in with some of our kin on McComb Street. It was kind of crowded there, but the house had toilets indoors and electric light. Down in Alabama, we had outhouses and kerosene lights.

Joe remembered that growing up, life was tough in Black Bottom even when the economy was jumping. When the Great Depression came it was hard times because blacks were often the last hired and the first fired, "My stepfather was let out at Ford's because the depression had come. My mother had gone down to the relief place and waited in line to get up a few bucks a week. We kept track of what we got and I paid it all back - $270."

People would ask me, "Joe, when you were a kid in Alabama, living sharecrop in a cotton patch, did you dream to be a millionaire and have rich things like cars, and pockets stuffed with money and fine clothes and all that? I say to them,

I couldn't dream that big."

Joe Louis

Pride of Black Bottom

Black Bottom before demolition

Black Bottom after demolition

Black Bottom was a tight-knit community. When a family fell on hard times, people didn't sit idly by as their neighbors' furniture was placed at the curb. They had rent parties and block parties where everyone brought food to sell to keep their neighbors from being evicted. There was no such thing as class distinction in Black Bottom. Doctors lived next to janitors, lawyers lived next to mechanics. It was the espirit de corps that helped Black Bottom survive during the all too frequent bad times

During good times or bad, there was always one escape, the entertainment district of Paradise Valley and its legendary thoroughfare, Hastings Street. Hastings Street was the Detroit version of Bourbon Street only with a Motown twist. Migrant Southern Bluesmen brought a unique style of blues which had never been heard at these Latitudes. Chief among them was a twenty-three years old Mississippian named John Lee Hooker. Hooker arrived in Detroit in 1943 and quickly made a name for himself. His eerie Delta moans and throaty wails simply couldn't be duplicated.

Hooker was at the head of a long procession of bluesmen that made Hastings Street synonymous with blues music. "Hastings Street was known more than any other in the U.S.," recalled Hooker. "Anywhere you'd go, you could hear people talking about Hastings Street." Like Harlem, whites also flocked to Hastings Street for the unequaled sounds and high times. Even celebrities like Jackie Gleason made it a point to stop by when he was in town. Hastings Street lit up like a Christmas tree at night, adorned with soulful music and sinful women.

But Hastings Street had a dark side to it. Blind pigs, the legacy of Prohibition, were too numerous to count and with them came poisonous swills, sometimes called 'bathtub gin' because it was made in a bathtub by amateurs. Prostitutes advertised under the corner street lights and muggers with razors laid in wait, hidden in the alley shadows.

When the destruction of Black Bottom began in 1951, some 140,000 blacks lived there. As the masses began fleeing the steam roller of urban renewal, many made their way over to 12th Street on the west side. Hastings Street was the last to go. As the wrecking ball worked it's way west, Hastings Street became an urban ghost town of abandoned bars and derelict buildings. Alas, in 1959, the menacing bull dozers stood at the foot of Hastings Street. History could wait no longer. It was the end of an era

Victim of Urban Renewal - An old bluesman who had played throughout Paradise Valley, brought his daughter for one last fleeting glimpse, telling her, "This is where Hastings Street used to be." It is now Interstate-375. The street which had become a rite of passage for southern blacks coming to Detroit was no more.

Detroit mayoral election of 1949

Chaos is Old Corktown

The urban renewal upheaval that saturated Detroit in the 1950's was not limited to the East side. The West side was scalped too, albeit on a smaller scale. Corktown, the West side enclave whose early Irish settlers came from Cork County, Ireland after the potato famine, was also earmarked by the city for urban renewal. Some 169 acres of this historic West side neighborhood were razed during the 1960's and 70's and replaced with light industry and warehouses.

The Irish had built a thriving community along Michigan Avenue in the 1800's. Many of the Irish moved out prior to the disruption of the urban renewal steam roller. They were replaced by in interesting fusion of Maltese, Mexican and African Americans who also came seeking prosperity. Below, an anonymous author poetically state his opinion of urban renewal and the changing times it brought to Corktown

Hastings Street was originally a Jewish thoroughfare where merchants plying their trade on push carts cluttered the streets and sidewalks. With the great black migration north in the 1910's & 20's came an influx of black, Southern bluesmen.

Jews slowly moved to the West side into the Dexter / 12th Street area. Hastings Street was transformed into an entertainment district and it's unique sounds were the original Motown sound, predating its well known successor by twenty years.

Condemned Corktown housing awaiting demolition

Skid Row - End of the Line

the grief caused by the wrecking ball. Michigan Avenue during the 1950's was every bit the eyesore

of Black Bottom and every bit as dangerous the the Wild West. Along the darkened recesses of Michigan Ave.

can be found a mystifying mixture of sleazy bars, pawn shops and flop houses that support the wretched refuse

of men who have lost it all.

Being a major thoroughfare of downtown Detroit, if the Model city was to shine like new money then skid row would have to go. Much like Black Bottom, the city would later find that getting rid of the eyesore didn't get rid of the people who formerly inhabited the area. Roughly speaking, they were just kicking the can a little further down the road. Many of these hard core people would simply moved over to the 12th Street / Linwood / Dexter area and the very same problems of the 1950's would re-materialize in the 1960's.

Where there is destitution, exploiters are sure to follow. Michigan Avenue in the 1950s with its seemingly endless rows of graft to satiate the down and out.

Skid Row, which extended along much of Michigan Avenue westward from downtown into Corktown, was also razed to make room for businesses and the Lodge expressway. Many of its occupants found themselves scrambling for sanctuary. As was the case on the East side, many fled to 12th Street, quickly making it the densest population in the city. Naturally, Skid Row held more than its fair share of nefarious characters who were soon to call 12th Street home, much to the chagrin of its long-time residents. The end result was the highest crime rate in the city and a ticking time bomb awaiting detonation.

Blood banks are prime sources of income for one element of skid row. The tramp will sell a pint of blood for $6, wait a few days before visiting another, sell another – a process that ends with a lowered iron content in his body and perhaps an emergency run to a hospital for an injection of blood he may have sold a week before.

For policemen, the job is as much one of serving to protect the residents of skid row from each other, as it is protecting others from them. A Wayne State sociologist reports that the alcoholism rate on the row is probably not much higher than the 5 or 6 percent addiction in the “outside” population. Father Vaughan Quinn, a Roman Catholic priest who works on the row, estimates the proportion of clinical alcoholics on the row is about a third.

Col. Harold Clemens, of the Volunteers of America, who has spent 40 years in skid rows across the country, operates a men’s home at 6060 Rivard. He says most of the homeless get that way in a progression beginning with a breaking of spirit because of some personal problem, often divorce. This is followed by a breakdown of morals, and then financial ruin. Of the 108 men quartered at the Salvation Army Harbor Light, 35 percent are under 50 years of age. Most die 15 years before the average life expectancy for men (70 years).

Corktown, the venerable west side enclave which for decades has been home to Irish immigrants, also took quite a beating when urban renewal came knocking. Much pain was encountered when Corktowners saw the dwelling they had spent their whole life in smashed to kindling.

His 'Fair Deal' made urban renewal possible.

Detroit's Urban Renewal Program 1940s - 1970s