The Miriani Crackdown

Election night (November 1961) - The newly elected Jerome Cavanagh addresses both stunned and jubilant supporters after learning of his upset victory. He had done what they said couldn’t be done.

He had caught lightning in a bottle and swept the endorsement-laden incumbent into the dustbin of history. Like the tragic Shakespearean character Julius Caesar, Cavanagh’s zenith would rise to incredible heights and his fall would be just as spectacular.

In the winter of 1960 Detroit witnessed a surge of criminal activity which included the brutal murders of Donahue and James. At 8:00 a.m. on the morning of December 7th, the twenty-three year old Donahue was to unlock her place of employment but instead found the door already unlocked. As she walked in she was startled to see a man at her desk who then lunged at her with a knife, stabbing her numerous times. After stealing her wallet he fled the scene. Donahue’s dying description of her attacker revealed he was black, twenty-five to thirty-five years old, 5’5” to 5’8”, and he wore dark, shabby clothes. She recalled that he had been in before looking for odd jobs.

Betty James

Twenty-six year old Betty James, a mother of three, met her fate later in the month when on the 27th of December she attempted to walk the four short blocks from Woodward to Children’s Hospital where she worked. She never made it. She was mugged by a black man who bludgeoned her with a four pound brass bar and then robbed her, fleeing the scene after witnesses sounded the alarm. They described him as a heavyset black man about thirty-five years old and 180 pounds. Betty James died shortly thereafter from massive head wounds.

Herbert W. Hart

Detroit Police Commissioner

1960 - 1962

Mayor of Detroit

1957 - 1962

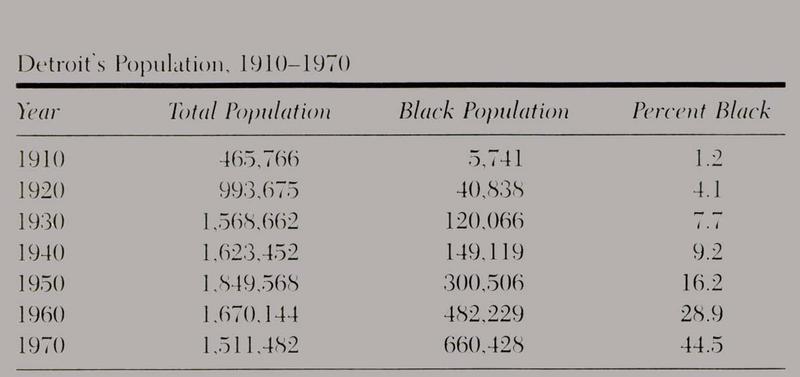

In the end he followed his constituents and, with the black population now at a viable 30 percent, his decision would cost him the 1962 election.

Jerome Cavanagh - A Last Flicker of Hope

Since the tragic fallout of the Civil War, America wandered aimlessly in search for a more progressive and egalitarian society.

Jerry Cavanagh was reared during the agony of the Great Depression and like so many others the lean times and the charismatic Franklin Roosevelt made a lasting impression on him. Roosevelt was the hero of the Depression era because he cared about the little guy, a lesson the young Cavanagh took to heart.

Detroit’s “boy mayor” entered office at the height of the civil rights movement, taking over a city that LOOK magazine once sardonically rasped “was noted for three things: automobiles, bad race relations and civic sloth.” Such was Detroit’s image in 1961. Cavanagh would thrust Detroit into the national limelight as an exemplar of social progress and tranquility amidst an oasis of public revolt. As one city after another went up in flames during the rebellious 1960s, leaders across the country held Detroit up high as the one city, because of its enterprising young mayor, that would not riot.

1962 - With the highest hopes of the city of Detroit, Jerome Patrick Cavanagh takes the oath of office at the tender age of thirty-three. A little known lawyer, his stunning upset of the incumbent Miriani sent a message to Detroiters that for the first time blacks had power at the voting booth. Detroit staged a remarkable comeback under Cavanagh. Regarded as a Kennedy type figure, his youth and insight represented the new breed of politician emerging across America.

Cavanagh had his hands full upon entering office, and not just with his eight kids.

The city was $19 million in the red when Cavanagh took office with the stark reality of a $34 million deficit looming by summer of '62.

Cavanagh’s tenure would be closely linked with President Johnson’s Great Society. Johnson’s War on Poverty was aimed at assisting urban children to obtain better housing, health care, education and job opportunities. Cavanagh had already launched a similar program called TAP (Total Action against Poverty). Johnson’s added federal muscle would give TAP some tiger-like teeth to attack with.

LBJ’s Model Cities Program sprouted up from a rather incongruous kernel. It was the Watts Riot during the summer of ‘65 that shocked Johnson into action. Johnson, like many others, was chagrined by the behavior of black militants. Like no other president before him, he attempted to free the black man from the bondages of poverty and prejudice by passing groundbreaking civil rights legislation, only to see one American city after another ignited by the flame of rebellion. Many whites who were initially sympathetic to the black cause would eventually turn a cold shoulder to civil rights, unable to differentiate between altruist and anarchist.

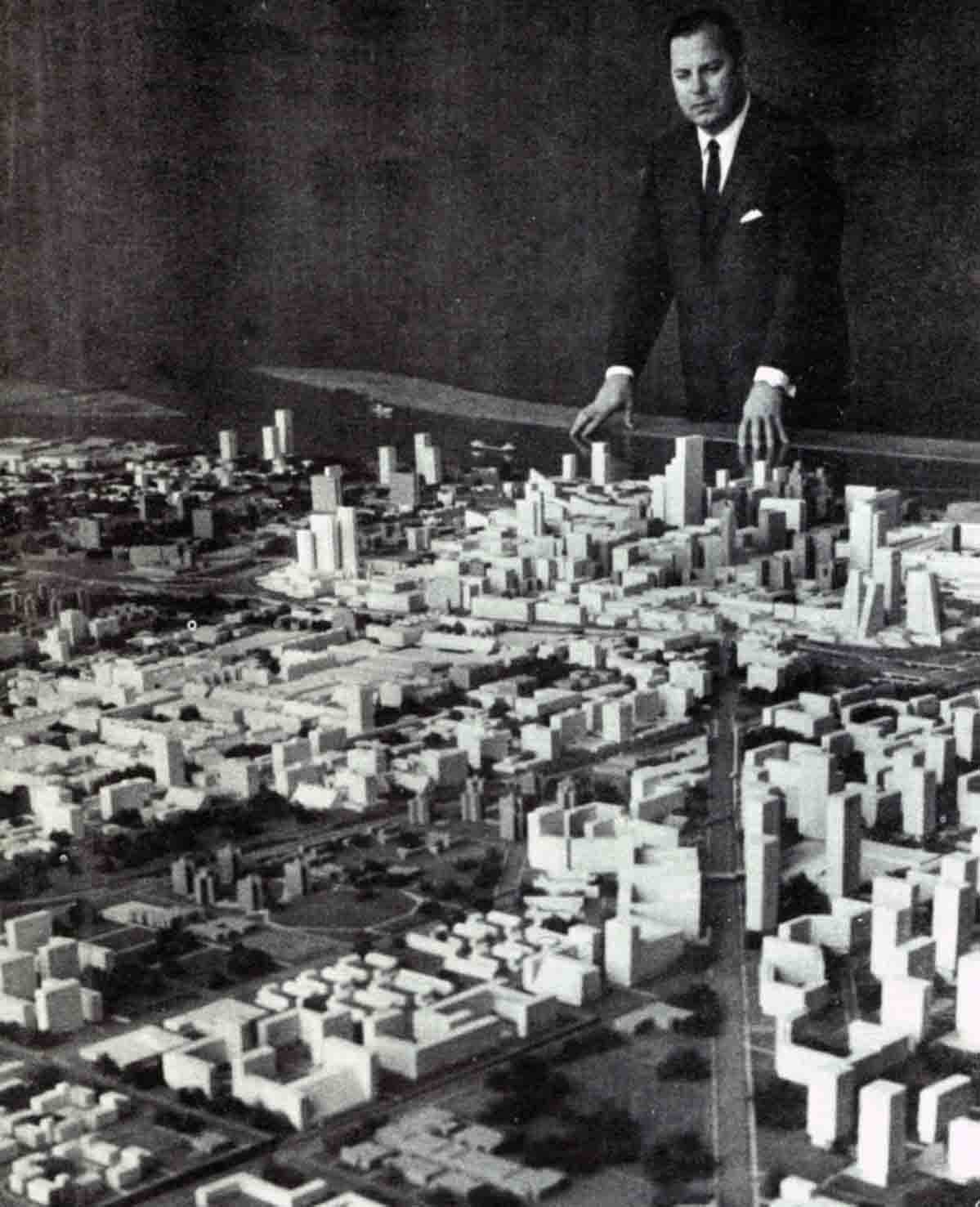

In September of 1965, Cavanagh, along with UAW president Walter Reuther, prodded President Johnson into selecting a pilot city to shower with federal grants and demonstrate to the nation how a large urban area can be rehabilitated physically and socially when properly equipped. Not coincidently, the two gently cajoled Johnson into believing that Detroit would be a good candidate.

Originally dubbed the “Demonstration Cities Program” (a very poor choice of words in this era of massive counter demonstrations, many people completely misunderstood its intentions), later renamed the Model Cities Program, it was provided with an initial fund of $400 million per year. Its focus was to eradicate slums and replace them with low to moderate cost housing, attack inner-city poverty by bolstering social programs, providing jobs, health care and recreational facilities, all of which would help keep young people off the street and learning instead of rioting. Cities that applied to become a much heralded Model City

had to demonstrate their need and have a workable plan to carry out their request.

Cavanagh had Washington's ear from the onset. Above, Cavanagh and Detroit Police Commissioner George Edwards pay a visit to the White House and new President John Kennedy. Kennedy's untimely demise would put Cavanagh into the hands of of Lyndon Johnson, a bird of a much different feather. While Johnson lacked the personality of his predecessor he was a giant in the political arena. Johnson needed salesmen for his Great Society programs and Cavanagh was eager to accept the help. But as the Vietnam War raged on through the 60s, Cavanagh would run afoul of LBJ because of his anti war sentiments.

Below, Cavanagh presents LBJ with the Spirit of Detroit, a symbol perhaps reminiscent of Cavanagh's tenure over the troubled city.

By 1965, Detroit had become a Model City not only in name but most certainly in stature. Detroit had gained national acclaim as a truly progressive city in a time when many were still regressing. By placing respected liberals in charge of the police department, capturing the lion’s share of War on Poverty funds and hosting the highly vaunted March for Freedom, Detroit was enjoying its time on top of the national pedestal. Detroit had become the “city upon a hill, for all eyes to see.”

The fresh young face that took Detroit by storm just five years earlier had aged noticeably. It would get considerably worse. Cavanagh’s wife was suing him for separate maintenance, a city council member started a recall petition against him, and in July of ‘67 his city had a date with destiny. For Detroit’s Caesar, the Ides of March had finally arrived.

The view from defeat - A haggard Mayor Cavanagh inspects the ruins of his city after the riot and is confronted by a youth. Cavanagh had no answers for him, nor should he have. He did everything possible to diffuse the time bomb his predecessors had handed him but in the end there were too many fuses and too many sparks to curtail.

After the conflagration of Watts in August of 1965, big city mayors began preparing for the worst. The Detroit police department’s primary riot busting apparatus for decades were the Commandos. Their ferocious reputation, which was well earned, often caused more trouble than it quelled. Cavanagh knew all about the overly aggressive methods of the Commandos and sought to organize a derivative of them that had the same hardened toughness but was not bent on proving it to society.

(Above) Cavanagh watches the newly formed Tactical Mobile Unit (TMU) of the Detroit Police Department drilling on Belle Isle in the fall of 1965. The special quality differentiating the TMU from the Commandos was that they could absorb physical and verbal abuse (i.e., spitting, rocks, obscenities) without reacting. It was a necessary adjustment in the boiling ghettos across the country that were ignited one after another from routine police incidents that quickly ratcheted out of control. If trouble came to Detroit, Cavanagh believed Detroit would be ready.

"And if, 2,000 years from now, our foolishness has laid us waste, I wonder

if the archaeologists will poke around the ruins of Detroit. Civilizations are

measured by their cities and I wonder what they will say of us and what

we have done."

- Jerome Cavanagh