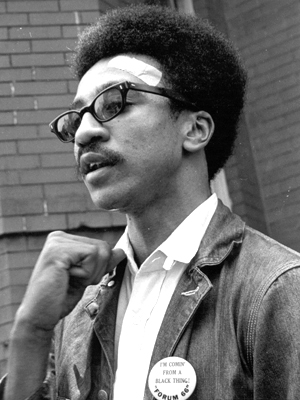

While his methods may have seemed crude and his language insidious, it was the H. Rap Browns of the world who forced to the surface the ugly and naked truth that America had not progressed since the Civil War and the silent majority were content to honor dead beliefs from a still born Constitution. It was the H. Rap Browns of the world, the street corner demagogues, who resorted to gangster tactics not because of a criminal gene in their DNA but rather than become another nameless victim of history they chose to rise up much like Washington and Adams did long ago, to right oppressive wrongs foisted upon them.

H. Rap Brown came along at a unique tipping point of history. With the death of Malcolm X in 1965, Brown would become the eye of the black rage and the voice for militant black America during the turbulent 1960s. Despite his multitude of protestations against white society encompassing decades, Rap will always be inextricably linked to the Cambridge riot of July, 1967. The question still begs after all this time, was he right or wrong?

White America was not interested in the black history lessons that Brown articulated because they did not believe nor did they want to hear the naked truth, that there was an avalanche of evidence implicating white America in its monomaniacal obsession of building and enforcing the white power structure and thus keeping the black man down. Brown was never worried about the repercussions from his actions thus making him a dangerous galvanizing apparatus, capable of harnessing the smoldering ghetto anger and commanding a scorched earth policy. Like the mythical Captain Ahab, Brown's well founded hatred for white society masked all caution and painted him into a corner of trouble he would never emerge from.

A sociology major from Southern University, Brown was never one to see the world in shades of gray. “I lived near Louisiana State University, and I could see this big fine school with modern buildings and it was for whites. Then there was Southern University, which was about to fall in and that was for the niggers.”

After visiting his brother at Howard University in Washington, D.C., Brown caught the civil rights bug and joined SNCC (Student Nonviolent Cooridating Committee). SNCC was originally a nonviolent student organization which specialized in marches and sit-ins to bring attention to civil rights infractions. After the Watts Riot, however, SNCC began to distance itself from its nonviolent theme under the direction of Stokley Carmichael. Brown was a lieutenant of Stokely Carmichael’s at SNCC. When Carmichael left SNCC, he turned over the reins of leadership to H. Rap Brown, it came with a warning, “You’ll be happy to have me back when you hear from Brown. He’s a bad man.”

Brown's summer excursions to visit his brother Ed in Washington would bare a heavy influence on him. It wasn't the every day theatrics in the nations capital that caught Brown's attention but the endless injustices across Chesapeake Bay that mesmerized him. Brown's destiny would become inextricably linked with Cambridge, Maryland and his actions there in July of 1967 would quickly propel him to the FBI's most wanted list and make him the most dangerous militant in America.

Cambridge - Through the looking glass

Cambridge, Maryland. Fifty miles from Washington D.C. and a million miles from civilization. A days hike to the citadel of democracy but a light year from New Deal egalitarianism. Cambridge was once a stop for the Underground railroad. A place were slaves could seek escape but 100 years later there was no escaping the destitution that seemed to haunt the area.

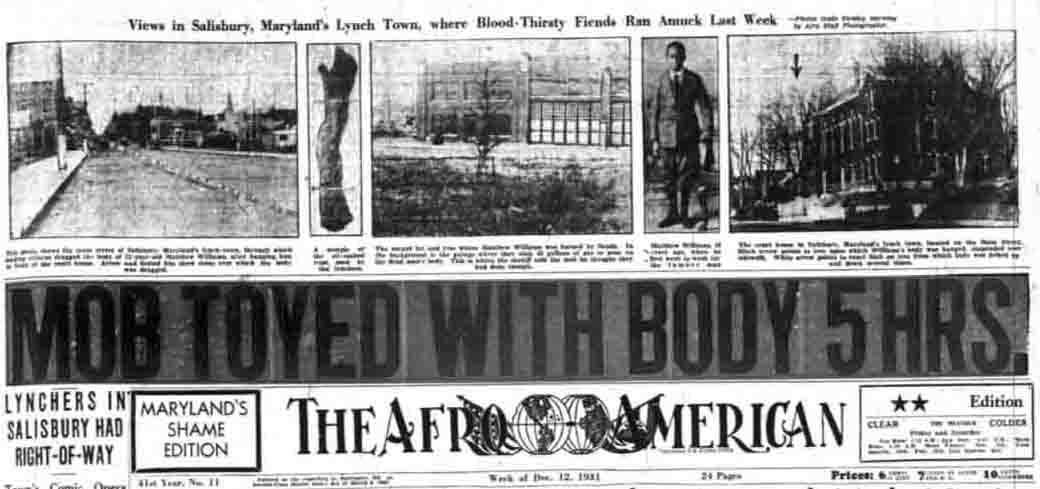

Lynching's, like the 1931 dismemberment of Matthew Williams in nearby Salisbury, denoted the violent tendencies which inundated Maryland's Eastern Shore and a lack of will power in enforcing the law. Lynching's also served to enforce the various types of oppression meted out by the power structure.

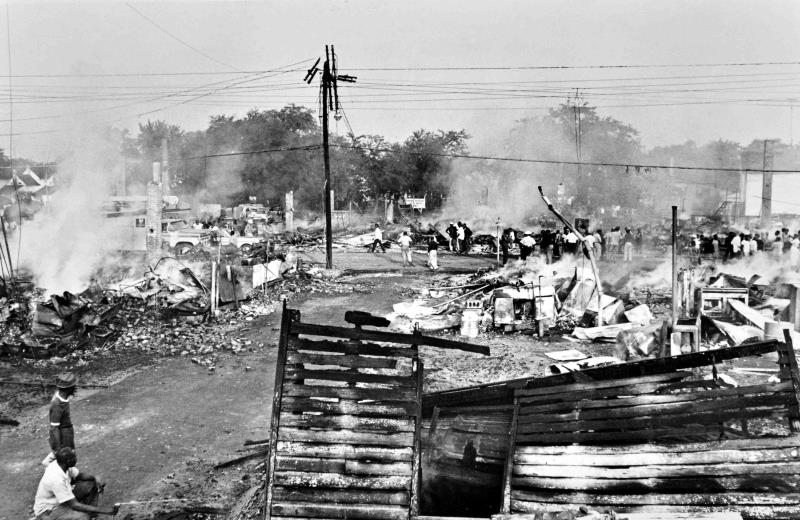

As a result, the area became a powder keg for race relations and it was just a matter of time before a triggering mechanism came along looking to right past wrongs. There message would not fall on deaf ears.

1931 – Black and white fishermen became reluctant allys and go on strike to protest low wages on the Eastern Shore. Matthew Williams (above) was charged with shooting his boss over a wage dispute. Shortly thereafter, he was brutally lynched, torn limb from limb and burned, his carcuss left as a reminder for all to see.

Cambridge - The Aftermath

1964 – George Wallace, the segregationist governor from Alabama, has decided to kick off his presidential campaign in, of all places, Cambridge, to an all-white audience. The black community recognizes this as calculated disrespect and organizes a march to protest. A wall of Guardsmen brandishing carbines, bayonets and gas masks blocks their progress. General Geltson demands they turn back because they don’t have a permit. Richardson asked if George Wallace has a permit. Guardsmen saturate the air with pepper gas. Those who can disperse run for their lives. Others simple collapse and convulse helplessly. Guardsmen begin firing indiscriminately into the fleeing crowd.

1937 – The giant Phillips Packing Company, a mundane cannery that dominated the area not only physically but socially, employed most of the areas work force and thus dictated terms. Many of the jobs in the poverty stricken 2nd ward of Cambridge were seasonal and thus in high demand. Much like the towering plantation houses that once dominated the area, now Phillips was the house on the hill. The tyrannical plantation master now replaced by a shop foreman and manager. Despite the racial tensions that had an endless grip on the city, destitute blacks and whites become reluctant allys and go on strike at Phillips to protest poor conditions.

1961 – Freedom Riders pass through Cambridge and catch the attention of Cambridge resident Gloria Richardson. While the Cambridge city government, which had come to personify the perpetuation of Jim Crow right under the eyes of the federal government across the bay, tried with little success to pave over its smoldering racial issues. They had not reckoned with local activist Gloria Richardson, however. Richardson's bitter memory of her uncle dying young because the local segregated hospital would not treat him would haunt her and she would direct her vengeance on a system of oppression that was cemented in place.

1962 – With the collapse of Phillips Packing, Cambridge, which always struggled with economic opportunity, now has a staggering 29% black unemployment. Factories have closed or moved on. Remaining factories, reluctant to hire blacks not just because of their color but their persistence in union activities, hire predominantly white employees.

1963 - In reprisal, protestors hit the street with a new vigor but so did the authorities. The result of this caustic cocktail of betrayal led to escalated violence which in turn led to martial law. Cambridge was quickly becoming a new home for the Maryland National Guard who cordoned off the entrances to the black 2nd ward every night to keep the vigilantes out (or, as many suspected, to keep the blacks in.)

U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy is appalled at the daily debacle across the bay. He calls a meeting between protestors and politicians to mediate grievances. The result is the "Treaty of Cambridge" which promises to desegregate public facilities, build public housing and begin the process of hiring blacks into city government. Without Kennedy constantly riding shotgun over public officials, the "promises" are slowly reneged on and the war on the shore escalates, ending with martial law and the constant occupation of Cambridge by the Maryland National Guard.

1967 - Summer Lightning

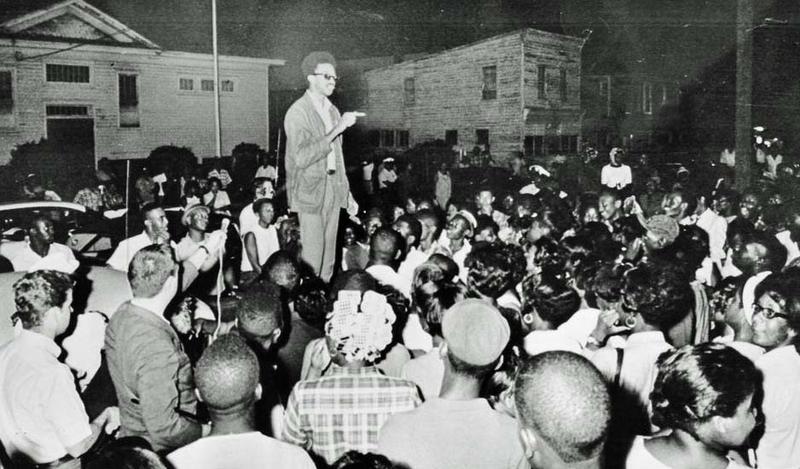

H. Rap Brown was invited by local activist Gloria Richardson to speak at a rally. Brown was no stranger to Cambridge, having protested in the city on numerous occasions in recent years. But Brown was more of a student in those days, watching the rebellious senior leaders work the crowds with their vitriolic rhetoric before the jobless and silent. Now it was Brown's turn to part the Red Sea of racism and tortured Cambridge would be that proving ground.

(Listen to entire recording of Brown’s Cambridge speech below)

With Brown’s diatribe now expended, he led his cadre of converts down Race Street only to be fired upon by the local police. Brown received a shot-gun pellet about the left eye. He was quickly spirited out of town by concerned supporters. Only hours after his departure was the Second Ward engulfed in flame.

1960s - By the 1960's, Cambridge is still as segregated as any hamlet in Mississippi. When the ambassador from the African country of Chad is refused service in the area, he complains to the Kennedy White House and the Freedom Riders decide to target Cambridge. The thorny subject of civil rights was political kryptonite. Presidents refused to deal with the problem but by the 1960s the subject was rearing its ugly head for everyone to see and now JFK and LBJ were forced to take action.

The most dangerous person in any society is the one who believes they have nothing to lose. (Left) Cambridge resident and activist Gloria Richardson was the lone voice in the wilderness that the government, despite considerable effort, could not silence. As the struggle for civil rights escalated, she brought in heavy weights Stokely Carmichael (Middle) and H. Rap Brown (Right). Between the three, the ugly chapter of Cambridge which for decades festered right under the nose of Washington, would be brought to the forefront for all to see.

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||